Presented by Zia H Shah MD

Audio teaser:

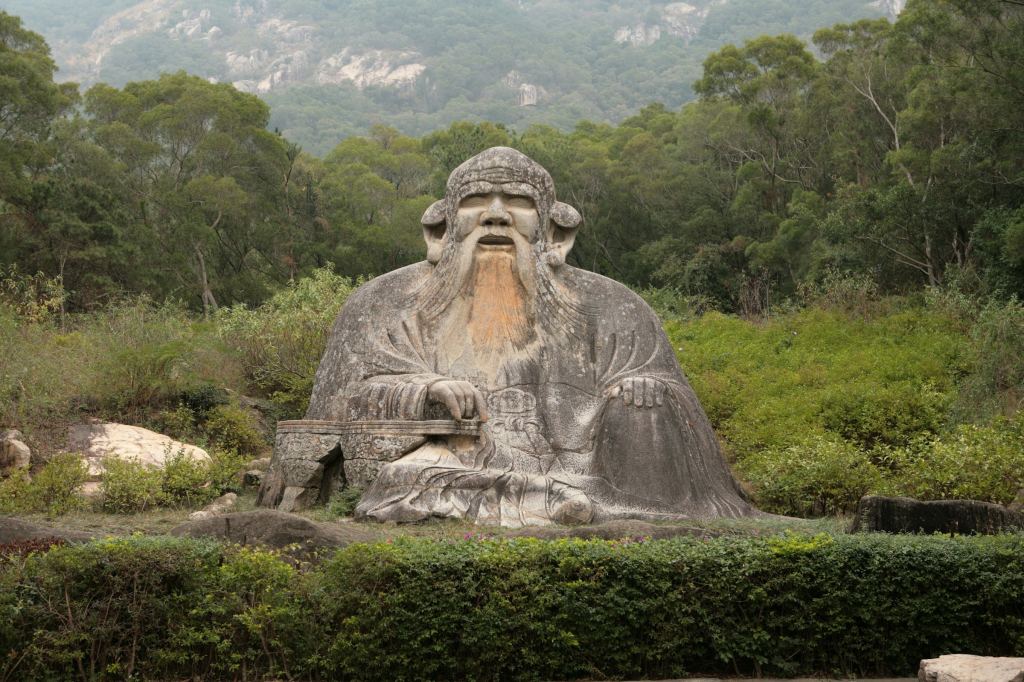

1. Introduction: The Enduring Shadow of the Old Master

In the tapestry of global intellectual history, few figures occupy a space as paradoxical as Lao Tzu (Laozi). Revered as the founder of Daoism, a deity in religious pantheons, and a strategic consultant to modern CEOs and political leaders, Lao Tzu represents a philosophy that champions the formless, the nameless, and the silent. Yet, his influence has generated a cacophony of interpretation spanning two and a half millennia. Today, as the People’s Republic of China asserts a renewed cultural confidence on the world stage, the wisdom of the “Old Master” has been excavated from the archives of antiquity and repurposed as a pillar of “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics,” influencing everything from ecological policy to geopolitical soft power.

This report seeks to provide an exhaustive examination of Lao Tzu’s life—balancing the tenuous historical record with the robust mythological tradition—and his profound, albeit complex, impact on the sociopolitical fabric of modern China. Furthermore, it addresses a unique comparative dimension: the striking philosophical resonance between Lao Tzu’s Daoist teachings and the theological and ethical frameworks of Islam. Central to this inquiry is the analysis of the apocryphal yet widely cited maxim: “Watch your thoughts, they become your words; watch your words, they become your actions; watch your actions, they become your habits; watch your habits, they become your character; watch your character, it becomes your destiny.” By deconstructing this quote and juxtaposing it with Islamic scripture and the sayings of Imam Ali ibn Abi Talib, this report illuminates a shared universal wisdom regarding the architecture of human destiny.

2. The Historical and Mythological Biography of Lao Tzu

To understand the influence of Lao Tzu, one must first navigate the labyrinth of his identity. Unlike the relatively well-documented life of Confucius (Kongzi), Lao Tzu exists in the misty borderlands between history and hagiography. The very name “Lao Tzu” is an honorific, translating simply to “Old Master,” leaving his true identity a subject of perpetual scholarly debate.

2.1 The Records of the Grand Historian

The primary source for any biographical reconstruction of Lao Tzu is the Shiji (Records of the Grand Historian), completed by Sima Qian around 100 BCE.1 Sima Qian, writing centuries after Lao Tzu’s purported lifespan, approached his subject with the caution of a historian confronted by conflicting oral traditions. He presents not a singular, unified narrative, but a composite dossier of possibilities.

According to the standard account in the Shiji, Lao Tzu was born Li Er (courtesy name Dan) in the village of Quren, located in the Hu district of the State of Chu (modern-day Luyi County in Henan Province).1 The specific timeframe is traditionally placed in the 6th century BCE, during the Spring and Autumn Period, making him an older contemporary of Confucius.

The Keeper of the Archives

Lao Tzu’s professional life is of immense symbolic importance. He is recorded as having served as the Shi (Keeper of the Archives) for the Royal Court of the Zhou Dynasty in Luoyang.1 This role was not merely clerical; the Zhou archives were the repository of the empire’s divinatory records, genealogical histories, and sacred rites. As the custodian of this knowledge, Lao Tzu would have witnessed the cyclical rise and fall of political fortunes, the futility of human ambition, and the inevitable decay of institutions. This vantage point likely fertilized the seeds of his philosophy: a skepticism toward artificial structures and a preference for the enduring, cyclical patterns of nature.4

2.2 The Encounter with Confucius: The Dragon Metaphor

One of the most culturally significant episodes in Sima Qian’s biography is the meeting between Lao Tzu and Confucius. This encounter represents the clash and complementary nature of China’s two dominant philosophical streams: Confucianism (focused on social order, ritual, and humanism) and Daoism (focused on natural order, spontaneity, and mysticism).

The legend recounts that Confucius, seeking to restore the fraying social fabric of the Zhou order, traveled to Luoyang to consult Lao Tzu regarding the performance of rites (Li). Lao Tzu’s response was a devastating critique of Confucian vanity and the futility of trying to engineer social harmony through rigid codes:

“The men about whom you talk are dead, and their bones are mouldered to dust; only their words remain. When the hour of the great man has struck he rises to leadership; but before his time has come he is hampered in all that he attempts. I have heard that a good merchant, though he has rich treasures deeply stored, appears as if he were poor, and that the superior man whose virtue is complete, is yet to outward seeming stupid. Put away your arrogant airs and many desires, your insinuating habit and wild will. These are of no advantage to you. This is all I have to tell you.” 2

Confucius, rather than responding with defensiveness, was reportedly awestruck. Upon returning to his disciples, he described the Old Master with a metaphor that has come to define Lao Tzu in the Chinese imagination:

“I know how birds can fly, how fish can swim, and how animals can run. But the runner may be snared, the swimmer may be hooked, and the flyer may be shot by the arrow. But there is the dragon. I cannot tell how it mounts on the wind through the clouds and rises to heaven. Today I have seen Lao Tzu, and can only compare him to the dragon.” 2

This comparison highlights the Daoist ideal: unlike the bird or fish which are defined and limited by their medium (and thus vulnerable), the dragon is transformative, elusive, and aligned with the elemental forces of change. It suggests that while Confucius sought to master the human world, Lao Tzu had transcended it.

2.3 The Departure at Hangu Pass and the Genesis of the Text

The final act of Lao Tzu’s biography is his departure, a narrative device that emphasizes the reluctant nature of his teaching. Witnessing the moral and political disintegration of the Zhou Dynasty, Lao Tzu resolved to retreat into the anonymity of the western wilderness—a symbolic return to the uncarved block of nature.3

Riding a water buffalo—an animal representing the harnessing of primal energy through gentleness rather than force—he arrived at Hangu Pass, the strategic gate separating the Middle Kingdom from the “barbarian” west. The guardian of the pass, Yin Xi, recognized the sage and realized that his wisdom would vanish with him. He implored Lao Tzu: “Since you are about to retire, I insist that you write a book for me.”.3

In response to this compulsion, Lao Tzu stayed briefly (tradition says overnight) and composed a text of approximately 5,000 characters in two parts: one discussing the Tao (The Way) and the other discussing Te (Virtue/Power). This text became the Tao Te Ching (The Classic of the Way and Virtue). Having discharged this debt to humanity, Lao Tzu rode through the pass and “no one knows where he went.”.3

2.4 Historical Skepticism and the Composite Author

While the biography provides a coherent narrative, modern scholarship offers a more fragmented view. Textual analysis of the Tao Te Ching reveals variations in rhyme schemes, vocabulary, and philosophical emphasis that suggest the text is an anthology—a compilation of proverbs, poems, and oral teachings accumulated by a school of thought rather than a single author.1

Scholars posit that “Lao Tzu” may be a composite figure. Sima Qian himself expresses uncertainty, mentioning two other candidates:

- Lao Laizi: A contemporary of Confucius from the state of Chu who wrote a 15-part work on Daoism.

- Dan, the Astrologer of Zhou: A figure who lived over a century after Confucius’s death.2

Furthermore, the Tao Te Ching contains polemics against Confucian values (such as “benevolence” and “righteousness”) that became prominent only in the Warring States period (c. 475–221 BCE), suggesting the text reached its final form long after the purported lifetime of Li Er.3 Nevertheless, whether Lao Tzu was a man, a myth, or a lineage of teachers, his function in Chinese culture is singular: he represents the voice of the natural order, standing in eternal counterpoint to the social order of Confucius.

3. The Tao in the Machine: Lao Tzu’s Influence on Modern China

In the 20th century, Daoism faced severe suppression during the Cultural Revolution, labeled as “feudal superstition.” However, the reform era initiated by Deng Xiaoping and accelerated under Xi Jinping has seen a remarkable rehabilitation of traditional Chinese culture. Lao Tzu has emerged from the temples to become a guiding spirit for state policy, business management, and cultural diplomacy.

3.1 Political Philosophy: “Ecological Civilization” and Governance

The most explicit application of Daoist thought in contemporary Chinese politics is the concept of Ecological Civilization (Shengtai Wenming). Enshrined in the Constitution of the Communist Party of China in 2018, this policy framework seeks to transition China from high-speed industrial growth to sustainable, high-quality development.7

President Xi Jinping has frequently drawn upon traditional wisdom to articulate this vision, specifically citing the Daoist principle of the “Unity of Man and Nature” (Tian Ren He Yi). In his speeches, Xi has quoted the Tao Te Ching (Chapter 25):

“Man models himself on Earth, Earth on Heaven, Heaven on the Way, and the Way on that which is naturally so.” 9

This citation serves a dual purpose: it legitimizes environmental policy through indigenous philosophy rather than Western importation, and it frames sustainability not as an economic constraint but as a cosmic imperative. The policy of “Green waters and lush mountains are invaluable assets” is an operationalization of Lao Tzu’s warning against excessive intervention in natural systems.7

Table 1: Daoist Principles in Chinese State Policy

| Daoist Principle | Modern Policy Application | Rationale |

| Unity of Man and Nature (Tian Ren He Yi) | Ecological Civilization | Framing environmental protection as a restoration of cosmic balance rather than mere pollution control. |

| Wu Wei (Non-Action/Effortless Action) | Macro-Control Policies | Using indirect regulatory levers rather than heavy-handed intervention to guide the market (though this is selectively applied). |

| Governing a Great State is like Cooking a Small Fish (Chapter 60) | Stability Maintenance | Avoiding excessive tossing and turning (radical policy shifts) that would break the “fish” (social order). |

3.2 Soft Power and Cultural Diplomacy

While Confucius lends his name to the “Confucius Institutes,” the content of China’s soft power projection relies heavily on Daoist aesthetics and practices. The global popularity of Tai Chi, Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), and the wellness industry allows China to project an image of harmony, health, and holistic wisdom—attributes central to Lao Tzu’s teachings.1

In foreign policy, the influence of Wu Wei offers a strategic framework often contrasted with Western interventionism. Wu Wei in this context does not mean passivity, but rather “action through non-action”—waiting for the opportune moment, using the opponent’s momentum against them, and avoiding exhaustion through premature aggression.12 This aligns with Deng Xiaoping’s maxim “Hide your strength, bide your time,” a quintessentially Daoist strategy of remaining low and obscure (like water) to accumulate power. Even in the more assertive “Wolf Warrior” era, the underlying justification often invokes the Daoist inevitability of China’s rise as a “return to the root” or natural historical correction.14

3.3 The “Tao” of Business: Chinese Management Styles

A distinct “Chinese Management Style” has emerged that synthesizes Western efficiency with Daoist leadership principles. Prominent entrepreneurs like Jack Ma (Alibaba) and Zhang Ruimin (Haier) have publicly discussed their reliance on the Tao Te Ching.14

Leadership through Invisibility

Lao Tzu’s definition of the ideal leader—”When his work is done, his aim fulfilled, they will say: we did it ourselves” (Chapter 17)—has inspired a decentralized management model.17 Zhang Ruimin, for example, restructured Haier by eliminating middle management and creating thousands of autonomous “micro-enterprises” within the company. This “RenDanHeYi” model mimics the Daoist ecosystem: the leader sets the context (the Tao) but does not micromanage the specific actions of the units, allowing order to emerge spontaneously (Ziran).16

4. The Architecture of Destiny: Deconstructing the Quote

The user has specifically requested an analysis of the famous quote attributed to Lao Tzu:

“Watch your thoughts, they become your words; watch your words, they become your actions; watch your actions, they become your habits; watch your habits, they become your character; watch your character, it becomes your destiny.”

4.1 Textual Authenticity: The Myth of the Old Master’s Pen

Rigorous textual analysis confirms that this specific quote does not appear in the Tao Te Ching nor in the earliest commentaries of the text.19 It is a modern aphorism that has been retroactively attributed to Lao Tzu due to its philosophical resonance with his teachings. The quote has a convoluted lineage in the West, having been attributed to figures such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Frank Outlaw (late President of Bi-Lo Stores), and even Margaret Thatcher.22

However, the attribution to Lao Tzu persists because the logic of the quote is profoundly Daoist. It mirrors the Daoist emphasis on the microscopic origins of macroscopic events. As Chapter 64 states:

“A tree that fills a man’s arms grows from a seedling… The journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.” 25

In Daoist cosmology, the “Ten Thousand Things” (the manifest world) are born from the One, which is born from the Tao. The quote follows this same trajectory: the massive, unmovable reality of “Destiny” is born from the subtle, invisible reality of “Thought.”

4.2 Philosophical Analysis of the Causal Chain

Despite its apocryphal nature, the quote provides a perfect framework for understanding Daoist psychology and self-cultivation.

- Thoughts become Words: The internal energy (Qi) of the mind manifests as vibration (speech). In Daoism, a restless mind (full of desire) leads to chaotic speech. The Sage “knows and does not speak” (Chapter 56) because he understands that crystallizing thought into word limits the infinite potential of the Tao.

- Words become Actions: Speech acts are the bridge between the subjective and objective. To name a thing is to limit it, but also to enable interaction with it.

- Actions become Habits: This parallels the Chinese concept of Xi (practice). Repeated action creates a “rut” or groove in one’s existence. Daoism warns against artificial habits (Wei) and encourages natural habits (Ziran).

- Habits become Character: Character here equates to Te (Virtue/Power). Te is not moral dogmatism but the accumulated “charge” of one’s habits. A person who habitually acts in alignment with nature accumulates Te.

- Character becomes Destiny: Finally, one’s inner power (Te) dictates their trajectory (Ming) through the cosmos. Destiny, in this view, is not a fatalistic script written by a distant god, but the natural consequence of one’s resonance with the Tao. If your character is rigid, your destiny is to break; if your character is fluid (like water), your destiny is to overcome.

5. The Tao and the Deen: Parallels with Islam

The user explicitly requests a comparison between Lao Tzu’s philosophy—specifically the “Watch your thoughts” quote—and Islamic teachings. This comparative analysis reveals a profound convergence between the Daoist Way and the Islamic Path (Deen), suggesting a universal spiritual anthropology.

5.1 The “Watch Your Thoughts” Parallel: Imam Ali ibn Abi Talib

While the quote is misattributed to Lao Tzu, it has a documented and authoritative parallel in Islamic tradition, specifically attributed to Imam Ali ibn Abi Talib, the cousin and son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad, and a figure revered for his wisdom and eloquence (Nahj al-Balagha).

The Quote by Imam Ali:

“Look out for your thoughts, for they will become your words. Look out for your words, for they will become your actions. Look out for your actions, for they will become your habits. Look out for your habits, for they will become your character. Look out for your character, for it will become your fate.” 27

The structural identity is nearly exact. In the Islamic context, this logic is grounded in the spiritual science of Tazkiyat al-Nafs (Purification of the Self). The believer is commanded to guard the “fortress of the heart” (Qalb) because Satan’s whispers (Waswasa) begin as fleeting thoughts (Khatir). If these thoughts are not “watched” (guarded against), they take root as desires (Shahwa), bloom into sinful actions, calcify into habits, and eventually seal the heart, determining the soul’s ultimate destiny in the Hereafter.

The Hadith of Intention (Niyyah)

The foundational Islamic text supporting this chain is the famous Hadith narrated by Umar ibn al-Khattab:

“Verily, actions are but by intentions (Innamal a’malu bin-niyyat), and every man shall have only that which he intended.” (Sahih Bukhari & Muslim).30

This Hadith confirms the Daoist/Aliid insight: the visible reality (Action) is entirely dependent on the invisible seed (Intention/Thought).

5.2 Comparative Analysis of Key Concepts

The resonance between Lao Tzu and Islamic spirituality extends far beyond a single quote. Several core concepts mirror each other, bridging the gap between the Far East and the Middle East.

Table 2: Conceptual Parallels between Daoism and Islam

| Concept | Daoism (Lao Tzu) | Islam (Quran/Hadith) | Shared Insight |

| The Origin | The Tao (The Way/Source) | Al-Haqq (The Truth/Real) / Allah | The Ultimate Reality is singular, unnameable, and the source of all existence. |

| Trust/Flow | Wu Wei (Effortless Action/Non-forcing) | Tawakkul (Trust in God/Reliance) | Abandoning the ego’s anxiety over outcomes; acting naturally while trusting the Universal Order/God. |

| Virtue | Te (Inner Power/Virtue) | Akhlaq (Character/Disposition) | Virtue is an internal state of being, not merely adherence to external rules. |

| Simplicity | Pu (The Uncarved Block) | Fitra (Primordial Nature) | Humans are born in a state of purity; spiritual practice is a return to this original state. |

| Symbolism | Water (Yielding, Lowly, Life-giving) | Water (Source of Life, Purification) | Water symbolizes the highest spiritual state: humility, adaptability, and life-force. |

5.3 Wu Wei and Tawakkul: The Art of Surrender

The comparison between Wu Wei and Tawakkul is particularly illuminating.

- Wu Wei is often misunderstood as “doing nothing.” In reality, it is “doing nothing against the nature of things.” It is removing the friction of the ego so that the Tao flows through the individual.

- Tawakkul is the Islamic concept of trusting in Allah’s plan. A famous Hadith recounts a Bedouin asking the Prophet if he should tie his camel or trust in Allah. The Prophet replied: “Tie your camel and trust in Allah.”.32

This “Camel” metaphor perfectly encapsulates Wu Wei. Tying the camel is the natural, necessary action (aligned with the situation). Trusting in Allah is the detachment from the outcome (the internal peace). Both traditions teach that anxiety arises from the delusion that the ego controls the universe. By surrendering that delusion—through Wu Wei or Tawakkul—one achieves harmony.

5.4 The Metaphor of Water

Water is the central metaphor for the “Good” in the Tao Te Ching, and it holds a similarly exalted place in the Quran.

Lao Tzu:

“The highest good is like water. Water gives life to the ten thousand things and does not strive. It flows in places men reject and so is like the Tao.” (Chapter 8).14

The Quran:

“Have not those who disbelieve known that the heavens and the earth were of one piece, then We parted them, and We made from water every living thing? Will they not then believe?” (Quran 21:30).35

Both traditions use water to illustrate the power of the lowly. In Daoism, water conquers the hard (rock) by yielding. In Islam, water is the medium of life and purification (Taharah), essential for prayer. The spiritual aspirant in both paths must become “fluid”—adaptable to the vessel of destiny, washing away the impurities of the ego, and seeking the “low places” (humility) to be nearest to the Divine Source.

5.5 Te and Akhlaq: The Perfection of Character

Lao Tzu distinguishes between artificial morality (Confucian benevolence) and true virtue (Te). He argues:

“The man of superior virtue is not (consciously) virtuous; hence he has virtue. The man of inferior virtue never loses sight of his virtue; hence he has no virtue.” (Chapter 38).38

This mirrors the Islamic concept of Ihsan (Spiritual Excellence) and Makarim al-Akhlaq. The Prophet Muhammad said, “I was sent only to perfect good character.”.34 In Sufi thought, true Akhlaq is when good deeds flow from the believer naturally, without calculation or desire for recognition. Just as Lao Tzu’s Sage acts without expectation of reward, the sincere Muslim acts “only for the countenance of Allah” (Quran 76:9), dissolving the self in the act of service.

6. Conclusion

Lao Tzu, whether the historical archivist Li Er or a mythical composite of ancient wisdom, casts a shadow that stretches far beyond the Hangu Pass. His philosophy of the Tao offers a counter-narrative to the rigid structures of human ambition, advocating for a return to the natural, the simple, and the fluid.

In modern China, this ancient wisdom has been revitalized, serving as the philosophical bedrock for “Ecological Civilization” and a unique brand of soft power that emphasizes harmony and resilience. The Tao Te Ching is no longer a relic of “feudal superstition” but a manual for navigating the complexities of the 21st century, from corporate boardrooms to climate summits.

Furthermore, the comparative analysis with Islam reveals that Lao Tzu’s insights are not culturally isolated. The apocryphal yet profound maxim—“Watch your thoughts, they become your destiny”—serves as a perfect bridge between the Daoist cultivation of Te and the Islamic discipline of Niyyah. Both traditions agree that the macrocosm of destiny is forged in the microcosm of the heart. Whether through the lens of Wu Wei or Tawakkul, the lesson remains the same: true power lies not in conquest, but in surrender to the Ultimate Reality; true strength is found not in rigidity, but in the water-like fluidity that sustains all life.

Through this synthesis, we see that the “Old Master” and the “Final Messenger” speak dialects of a single, universal truth: that to master the world, one must first master the self.

Leave a comment