Epigraph:

Surely, the Believers, and the Jews, and the Christians and the Sabians — whichever party from among these truly believes in Allah and the Last Day and does good deeds — shall have their reward with their Lord, and no fear shall come upon them, nor shall they grieve. (Al Quran 2:62)

Presented by Zia H Shah MD

Abstract

Eva de Vitray-Meyerovitch (1909–1999) was a French intellectual, translator, and philosopher who dedicated her life to exploring and sharing the spiritual heritage of Islam. Born into a devout Catholic aristocratic family in France, she initially pursued studies in law and philosophy. Her encounter with the writings of Muslim poet-philosopher Muhammad Iqbal sparked a profound fascination with Islam’s intellectual and mystical traditions, especially the works of 13th-century Sufi poet Jalaluddin Rumi. In the mid-20th century, Eva embraced Islam herself—adopting the name “Hawa” (Arabic for Eve)—and became one of the foremost interpreters of Rumi in the West. Over her long career as a researcher at the CNRS and a lecturer at institutions like Al-Azhar University, she translated Rumi’s Persian poetry into French and authored around 40 books on Islam and Sufism. Her journey from a conservative French upbringing to a life immersed in Sufi spirituality exemplifies a personal quest for truth that transcended cultural and religious boundaries. Ultimately buried in Konya, Turkey—near Rumi’s own tomb—Eva de Vitray-Meyerovitch’s life story stands as a powerful testament to the possibility of deep understanding between the West and the Islamic world, offering an inviting new perspective of Islam to her fellow French compatriots.

Early Life and Education

Eva Lamacque de Vitray was born on November 5, 1909, in Boulogne-Billancourt, an affluent suburb of Parisen.wikipedia.org. Raised in an aristocratic and devout Catholic family, she was educated in strict parochial schools. From an early age, Eva displayed an independent and questioning mind. She challenged the religious assumptions around her and grappled with doctrines such as the Holy Trinity and the Eucharist, asking probing questions of priests about core Christian beliefs. This intellectual curiosity was likely influenced by her family environment—her Scottish Protestant grandmother, who had converted to Catholicism, instilled in young Eva an ideal of honesty and moral integrity in matters of faith.

Continuing her education, Eva studied law at university and began a doctorate in philosophy focusing on symbolism in Plato’s worksen.wikipedia.org. She also pursued broad intellectual interests, delving into Christian theology at the Sorbonne for three years, studying ancient Greek and Latin, and even taking courses in psychiatry to understand the line between normal and pathological symbols. This wide-ranging scholarly background gave her a firm grounding in Western philosophy and religious thought, preparing her for the comparative spiritual explorations she would later undertake.

In 1931, at age 22, Eva married Lazare Meyerovitch, a Frenchman of Jewish origin. Marrying outside her Catholic faith was a bold personal choice, reflecting her belief in the underlying spiritual commonality of different religions. During the 1930s Eva worked as an administrator in the laboratory of the renowned physicist Frédéric Joliot-Curie. When World War II broke out and Nazi forces occupied Paris in 1940, Eva, her husband, and colleagues fled the city. She spent the war years in the rural Corrèze region of France, while her husband served in the Free French Resistance forces. Eva’s wartime experiences, including witnessing or learning of atrocities (such as the massacre of hundreds of villagers by occupying forces), left her “thirsty for the Absolute” and deeply disillusioned with the cruelty humans could inflict. This spiritual restlessness set the stage for the transformative encounter that would soon occur in her life.

After France’s liberation, Eva joined the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) as a researcher and eventually became director of its Department of Humanitiesen.wikipedia.org. Though successful in her secular career, she was privately searching for deeper meaning to make sense of the suffering and moral questions raised by the war. It was at this juncture, in the early 1950s, that a chance gift from a friend opened an unexpected door for her.

Path to Islam and Sufism

Eva’s introduction to Islam came through literature rather than direct proselytizing. A former classmate from her student days—an Indian friend who had returned from newly formed Pakistan—visited her in the early 1950s and brought a parting gift: a book by the poet-philosopher Muhammad Iqbal. This book was The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam, Iqbal’s seminal work reconciling Islamic theology with modern ideas. Eva read Iqbal’s prose with astonishment; its combination of lucid reasoning and spiritual fervor “touched the heart of this intellectual and sensitive woman”. Particularly captivating were Iqbal’s frequent references to Jalaluddin Rumi, the mystical Persian poet. Iqbal’s writing conveyed Rumi’s ideas with such admiration that Eva “immediately became fascinated by this great soul” Rumi, even before reading his works directly.

Intrigued, Eva decided to translate Iqbal’s book into French and began studying Persian in order to read Rumi in the original language. For three years she immersed herself in Persian. Upon gaining proficiency, she started reading Rumi’s masterpiece, the Masnavi (Mathnawī), and was overwhelmed by the depth of its mystical insights. One passage that struck her was a cosmological metaphor from Rumi: “Even the minuscule movement of a person on the Earth is recorded by solar systems in undiscovered galaxies.” Eva was astonished that a 13th-century mystic could express a vision of interconnection that resonated with modern scientific understanding of the cosmos. This blend of poetry, spiritual wisdom, and almost scientific grandeur in Rumi’s thought convinced her that she had found a path to the “Absolute” she had been seeking.

Rumi in effect became Eva’s spiritual mentor across centuries—“as if he took her hand and led her to the Muslim path,” one commentator observed. Around this time, Eva experienced an inner calling to embrace Islam formally. She had already spent three years (circa the early 1950s) studying Christian exegesis at the Sorbonne, attempting to deepen her understanding of her birth faith. But the pull of Rumi’s Sufi Islam was strong. She later described discovering Islam as “a return to her homeland”—a coming home to a truth that felt innate.

Eva did not make the decision lightly. She consulted a Catholic monsignor for advice, who oddly suggested she consider becoming Protestant instead, as a “less jarring” change than Islam. Eva rejected this idea, feeling that one should not choose a faith by convenience: “Religion isn’t about cherry-picking the principles that suit you,” she reflected. In Islam she had found the clarity and coherence she craved. She recited the Shahada (Islamic testimony of faith), finding great peace in “surrendering to the will of God” and entering a religion that affirmed her continued reverence for Jesus and Mary while freeing her from theological doctrines she struggled with. In her view, Islam did not negate her former spiritual knowledge but completed it — she often remarked that Islam recognizes Judaism and Christianity as predecessors in a single tradition of true religion.

Upon converting, Eva took the Arabic name Hawwa, which is the exact equivalent of her given name Eve. This choice symbolized how her new faith was a natural continuation of her identity rather than an abnegation of her past. Embracing Islam in mid-20th-century France was not without consequences: Eva faced skepticism and even rejection from some friends, colleagues, and family members in her French Catholic milieu. At the same time, within Muslim communities she sometimes encountered the condescension reserved for converts, who were seen as newcomers to the faith. Undeterred, Eva pressed forward, determined to “fervently practice all the Islamic pillars” and deepen her involvement in Sufism, the mystical dimension of Islam that had drawn her in.

Her conversion also had a moral and political edge. The Algeria War of Independence (1954–1962) was raging at this time, straining relations between France and the Muslim world. Eva was appalled by how some of her compatriots regarded Muslims as inferiors, and by France’s colonial abuses. By becoming Muslim, she in effect “sided with a civilization many of her compatriots considered inferior,” bravely challenging the prejudices of her society. She did so without rejecting the truths of Christianity or Judaism that she still valued; rather, she felt Islam encompassed and fulfilled those earlier traditions. In her own words, Islam was Dīn al-Fiṭra, “the religion of [humanity’s] pure original nature,” a faith that felt like an intrinsic truth she had always known.

Scholarly Career and Works

Having embraced Islam and the Persian language by the mid-1950s, Eva de Vitray-Meyerovitch devoted the rest of her life to scholarship, translation, and teaching aimed at sharing the spiritual riches of Islam with a Western audience. She supported herself in part through her translation worken.wikipedia.org, and her scholarly output was prodigious: in total, Eva authored around forty books as well as numerous articles over her career. These works include both her own writings on Islamic spirituality and her translations of major texts from Persian and English into French.

One of Eva’s earliest translation projects was the very book that had inspired her – Muhammad Iqbal’s The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam, which she rendered into French (published in 1955). She also translated other works of Iqbal and, crucially, embarked on translating Rumi’s poetry into French. By the late 1960s, Eva’s expertise on Rumi was firmly established: in 1968 she completed a doctoral thesis titled Mystical Themes in the Work of Jalal ud-Din Rumi, which she defended at the University of Paris. This scholarly work delved into Rumi’s Sufi concepts and marked one of the first major French academic studies of Rumi.

Eva’s translations made Rumi’s writings accessible in French for the first time on a large scale. She produced French versions of Rumi’s Fīhi mā fīhi (Discourses), his Rubâ’iyyât (quatrains), and the Dīwān-e Kabīr (lyric poems), often publishing them with extensive annotations for context. Her crowning achievement was the French translation of Rumi’s Masnavi—a monumental six-volume Sufi poetic work of ~50,000 verses—which she completed after some fifteen years of labor and published in 1990. This Masnavi translation (titled Mathnawî – La Quête de l’Absolu, “The Quest for the Absolute”) was the first time Rumi’s magnum opus appeared in French in its entirety. It earned wide acclaim and reflected Eva’s dedication to conveying Rumi’s message of divine love and unity to Western readers.

Beyond translations, Eva wrote original books exploring Sufi themes and Islamic spirituality in terms a Western audience could appreciate. A few of her notable works include:

- Mystique et poésie en Islam (Mysticism and Poetry in Islam, 1972): An early study highlighting the interplay of spiritual experience and poetic expression in Islamic tradition.

- Rûmî et le Soufisme (Rumi and Sufism, 1977): A comprehensive introduction to Rumi’s life, teachings, and the Mevlevi Sufi order he inspired; this book was later translated into multiple languages, spreading Rumi’s “religion of love” globally.

- Anthologie du soufisme (Anthology of Sufism, 1978): A curated collection of Sufi writings across centuries, reflecting Eva’s broad knowledge of mystical literature.

- Jésus dans la tradition soufie (Jesus in the Sufi Tradition, 1985): Co-authored with Faouzi Skali, this work examines the revered place of Jesus in Islamic mysticism, underscoring the continuity between Christian and Muslim spiritual heritage.

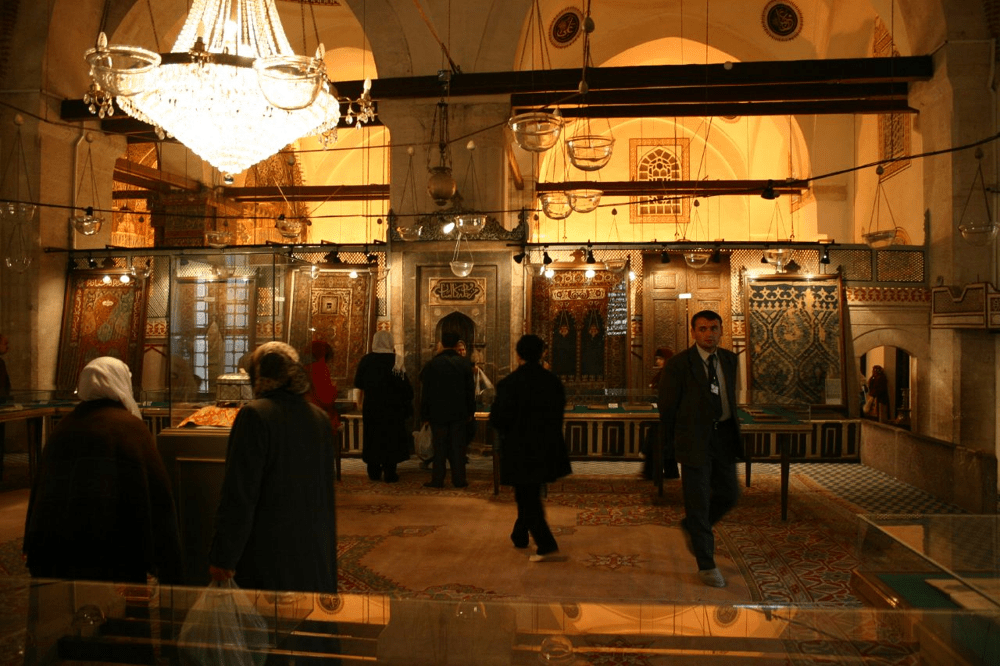

- Konya ou la Danse Cosmique (Konya, or The Cosmic Dance, 1990): A reflection on the whirling dervish ceremonies of Konya and their cosmic symbolism, published the same year as her Masnavi translation.

- Islam, l’autre visage (Islam, the Other Face, 1995): A book in the form of interviews with Eva (by Rachel and Jean-Pierre Cartier) in which she presents Islam’s spiritual and humanistic side to dispel Western misconceptions. This influential work – later translated into English as Towards the Heart of Islam: A Woman’s Approach – is “a beautiful, humble, powerful book; an invitation to meditation” that leaves readers with “a light heart,” as one review described.

- La prière en Islam (Prayer in Islam, 1998): Her final book, discussing the significance of Islamic prayer and spirituality, published just a year before her passing.

In addition to writing, Eva was an active educator. From 1969 to 1973, she lived in Egypt and taught philosophy at Al-Azhar University in Cairo – a remarkable role for a Western woman at the preeminent institution of Sunni Islamic learning. She served as an academic liaison representing the CNRS during this tenure and formed lasting friendships in Egypt. Eva also traveled widely to lecture on Islam and Sufism around the world. Whether speaking on Rumi’s poetry, the Qur’an, or the whirling dervishes, she had a talent for explaining spiritual concepts across cultural boundaries. In France, she recorded several programs for Radio France Culture and made television appearances to discuss Rumi, Sufi music, and Islamic civilizationen.wikipedia.org. Her erudition and passion earned her respect in both East and West. The Turkish authorities, appreciative of her work on Rumi, honored Eva by naming her a “Citizen of Honour” and awarding her an honorary doctorate from Selçuk University in Konya.

Throughout her scholarly career, Eva remained personally engaged in the Sufi path. In 1985, during a trip to Morocco, she met Shaykh Hamza al-Qadiri al-Boutchichi, a living Sufi master of the Qadiriyya orderen.wikipedia.org. Sensing her deep connection to Rumi, the shaykh warmly welcomed her (exclaiming “Rumi is here!” while pointing to his heart) and accepted her as a disciple. Eva continued to follow Shaykh Hamza’s guidance until the end of her life, incorporating the practices of a Sufi seeker (such as regular dhikr or remembrance of God) into her daily routine. She was also close to Khaled Bentounes, the head of the Alawiyya Sufi order in France, whose emphasis on universal love resonated with her values. Friends recall that Eva would often talk about Rumi’s Masnavi even while doing mundane tasks like knitting or cooking – a testament to how thoroughly Rumi’s teachings permeated her life.

Later Years and Legacy

Eva de Vitray-Meyerovitch lived a life that bridged cultural and religious worlds in a singular way. By the 1980s and 1990s, she had become a revered figure in French intellectual circles and among spiritual seekers worldwide. Her works had popularized Rumi in Europe at a time when his poetry was far less known in the West than it is today. Many credit her translations and lectures with paving the way for Rumi’s later international fame as a best-selling poet. Indeed, Eva saw it as an urgent mission to transmit Rumi’s universal message of love and unity to contemporary audiences, whom she felt were in great need of it. She also helped introduce generations of French readers to a compassionate, profound vision of Islam, countering stereotypes by highlighting the faith’s rich spiritual and intellectual traditions.

In France, Eva’s unique position as a Muslim woman scholar of both Western and Eastern tradition made her a valued “bridge” figure. She moved happily between East and West, exemplifying the possibility of being at home in both. As one biographer noted, she was “among the few persons who lived with such happiness between the East and the West, and who have been bridges between both cultures”. She counted among her friends and influences not only Sufi mystics but also renowned orientalists like Louis Massignon (who had been her mentor and supporter in the 1950s) and Henry Corbin, and writers like Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Martin Lings, and Annemarie Schimmel – all fellow pioneers in fostering a genuine encounter between Islam and the West.

Eva’s personal life had its share of trials. Her husband Lazare had died suddenly in the early 1950s, leaving her a young widow with two children to raise. Balancing motherhood with her intellectual and spiritual pursuits was challenging, but she managed with grace. Her children did not initially share her new faith, and this sometimes caused friction. Yet, Eva remained close to her family and maintained that becoming Muslim did not mean abandoning her love for her relatives or for France – it simply meant she had found her soul’s true path.

In her final decade, Eva continued writing and speaking. Her health began to decline in the late 1990s, but she stayed active as long as possible. In 1998, at age 88, she traveled one last time to Turkey for a conference, expressing while there her heartfelt wish to be buried in Konya near Rumi, whose presence she had felt guiding her for so many years. Eva de Vitray-Meyerovitch passed away in Paris on July 24, 1999, at the age of 89. Honoring her request proved complicated at first. She was quietly interred in France (at Thiais, near Paris) in a private ceremony, as some family members were hesitant to send her remains abroad.

However, Eva’s students and admirers in both France and Turkey did not forget her final wish. They established a foundation to preserve her legacy and kept working to fulfill her burial request. In 2008 – nearly a decade after her death and just within the legal window for exhumation – her remains were carefully transferred from France to Konya, Turkey. On December 17, 2008, a special ceremony was held in Konya during the annual Şeb-i Arus festival (the “Night of Union” commemorating Rumi’s passing). In the presence of local dignitaries and international friends, Eva was finally laid to rest in Konya’s historic Üçler Cemetery, “next to Hz. Mevlana’s tomb”, as she had desired. Her new grave site lies just opposite the mausoleum of Jalaluddin Rumi, symbolically resting in the revered poet’s shadow.

The ceremony that reburied Eva in Konya was a moving testament to her bridge-building life. People from many countries—France, Turkey, the United States, Spain, Lebanon and beyond—gathered at her graveside, drawn by what Rumi’s descendant Esin Çelebi described as “Ms. Eva’s spiritual invitation”. In an impromptu interfaith service, verses from the Qur’an were recited by a Turkish Hafiz, prayers were offered in English, French, and Spanish by various attendees, and finally a Mevlevi Sufi prayer was sung in Eva’s honor. It was an unplanned, heartfelt tribute that reflected the very essence of Eva’s legacy: unity in diversity. As Esin Çelebi observed, even after death Eva “received gifts” – her lifelong wish fulfilled and her story continuing to inspire others.

Epilogue

The life of Eva de Vitray-Meyerovitch is more than just an individual biography; it is an invitation to broader understanding. Her journey from the heart of French Catholic aristocracy to the embrace of Islam and Sufism challenges the notion of an unbridgeable divide between Western and Muslim worlds. In a time when misunderstandings between France and its Muslim citizens (and the Muslim world at large) have often led to friction, Eva’s example offers a different narrative – one of curiosity, openness, and profound respect. She approached Islam not as a foreign threat but as a long-lost “homeland” of the spirit, demonstrating that a French intellectual could find fulfillment and truth within Islam’s fold without losing her identity.

Eva’s legacy in France is significant. Through her translations and writings, she introduced countless French readers to the beauty of Rumi’s poetry and the humane philosophy of Islamic mysticism. Books like Islam, l’autre visage explicitly aimed to show her countrymen “the other face” of Islam – a face of compassion, wisdom, and peace that often gets obscured by political controversies. As a woman of letters and science who also lived as a devout Muslim, she embodied the compatibility of faith and reason, of Islamic devotion and French culture. It is telling that she felt most “at home” in Konya, yet remained deeply French in her intellectual style; she straddled both worlds comfortably. Turkish officials calling her a “Citizen of Honour” and French peers admiring her erudition both attest to the bridging role she played.

In reflecting on Eva de Vitray-Meyerovitch’s life, one cannot help but see a message of hope for cross-cultural harmony. Her “life of surrender to a higher purpose” – as one Sufi friend described it – stands as a “testimony of determination to transcend the fear of that which is different, in order to discover the encompassing love that connects us in all our rich diversity.” Her story shows that embracing another faith and culture need not be an act of alienation; it can be a path to discovering universal truths that unite humanity. In an era when French society continues to wrestle with questions of secularism, religion, and identity, Eva’s profound respect for Islam’s spiritual depth invites her fellow French to look beyond prejudice and see Islam in a positive light – not as l’Autre (the Other), but as part of a shared human quest for meaning.

Through Eva’s eyes, Islam appears not as a monolithic political force but as a vast spiritual treasury open to all who seek. Her own seeking was rewarded with a sense of homecoming and purpose. And in sharing her journey so generously through her writings and lectures, she extended an open hand to others. The many mourners from diverse lands who felt drawn to Konya for her reburial in 2008 testify that her influence transcended borders. Eva de Vitray-Meyerovitch’s life invites us — French and non-French alike — to approach one another’s cultures and faiths with humility and love. In the end, it is a life that reminds us, in Rumi’s poetic spirit, that “Love is the bridge between you and everything.” Each person who, thanks to Eva, comes to appreciate the beauty of Rumi’s verses or the serenity of a Sufi prayer is a person who sees Islam’s gentle light a little more clearly. This enduring influence is Eva’s final gift: an invitation to the heart, calling on us to replace fear with understanding and to recognize the divine light present in every tradition.

Sources:

- Geoffroy, Eric. Eva de Vitray-Meyerovitch, “Hawwa Hanim” (1909-1999), Rûmî’s French interpreter. Conscience Soufie – Cycle Hommage, 2007.

- Eva de Vitray-Meyerovitch – Wikipedia: Biography and bibliography of Eva de Vitray-Meyerovitch.

- Kılıckaya, Belkıs. “Portrait of a French Sufi on the Night of Reunion (Şeb-i Arus): Eva de Vitray Meyerovitch.” Politics Today, Dec 16, 2016.

- Çelebi Bayru, Esin. Eva de Vitray-Meyerovitch, un trésor de souvenirs. Conscience Soufie, 2018 – Remembrance by Rumi’s 22nd-generation granddaughter.

- Conscience Soufie Editorial. Bibliographie d’Eva de Vitray-Meyerovitch. Conscience Soufie (Cycle Hommage).

- Wikipedia (Français). “Eva de Vitray-Meyerovitch.” Last modified 2023 (source for career details).

- Geoffroy, Eric. Preface to Towards the Heart of Islam: A Woman’s Approach (Fons Vitae, forthcoming English edition of Islam, l’autre visage).

Leave a comment