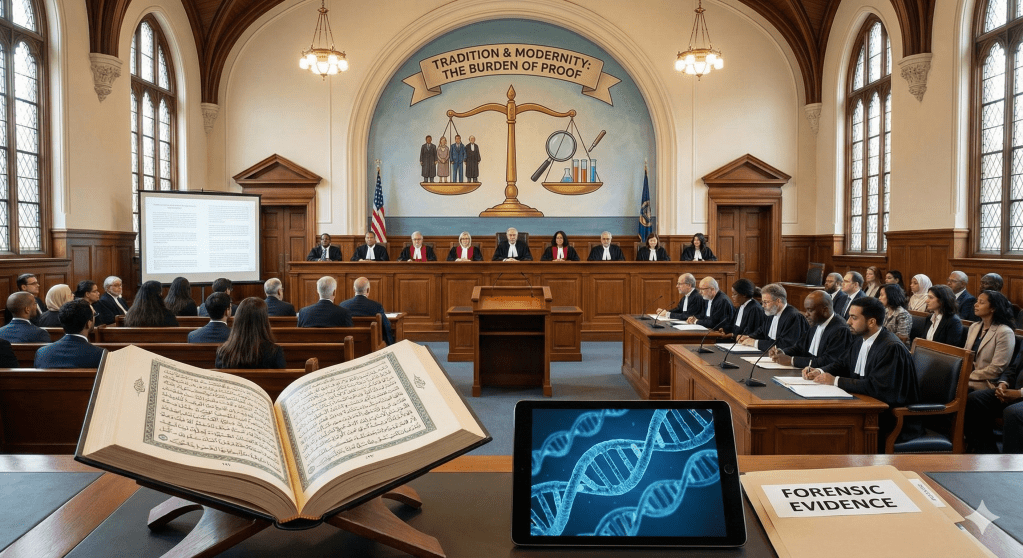

Epigraph

O ye who believe, seek the help of Alah through steadfastness and Prayer; surely Alah is with the steadfast. Say not of those who are killed in the cause of Alah that they are dead; they are not dead but alive; only you perceive it not. We will surely try you with somewhat of fear and hunger, and loss of wealth and lives and fruits; then give glad tidings to the steadfast, who, when a misfortune overtakes them do not lose heart, but say: Surely, to Alah we belong and to Him shall we return. It is these on whom are blessings from their Lord and mercy, and it is these who are rightly guided. (Al Quran 2:153-157)

Presented by Zia H Shah MD

Abstract

This comprehensive research report undertakes a rigorous comparative analysis of the foundational soteriological framework of Buddhism—the Four Noble Truths (Cattāri Ariyasaccāni)—and the corresponding theological, ethical, and mystical dimensions within Islam. While Buddhism and Islam emerge from distinct metaphysical landscapes—one non-theistic and centered on the cessation of cyclic existence (Samsara), the other strictly monotheistic and centered on submission to a Divine Will (Allah)—a detailed phenomenological examination reveals profound structural and functional parallels in their diagnosis of the human condition and their prescriptive methodologies for spiritual liberation.

The study is structured explicitly around the quadripartite formula of the Buddha: the Truth of Suffering (Dukkha), the Truth of the Origin of Suffering (Samudaya), the Truth of the Cessation of Suffering (Nirodha), and the Truth of the Path (Magga). Each truth is juxtaposed with Islamic concepts derived from the Qur’an, the Hadith corpus, and the classical commentaries of luminaries such as Abu Hamid al-Ghazali and Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyyah. The report argues that while the ontological foundations of the two faiths diverge—specifically regarding the nature of the soul (Anatta vs. Ruh) and the existence of a Creator—they share a sophisticated “technology of the self” aimed at mastering the ego, curbing appetitive desires, and rectifying human perception. Through a detailed exegesis of classical texts, including the Visuddhimagga and Ihya Ulum al-Din, this report illuminates how both traditions function as medical models for the human spirit, diagnosing the illness of existential dissatisfaction and prescribing a rigorous regimen of ethical discipline, mental cultivation, and wisdom to achieve ultimate peace.

Introduction: The Medical Model of Spirituality

In the annals of comparative religion, the dialogue between Buddhism and Islam has often been obscured by their divergent theological starting points. Buddhism, in its earliest Theravada formulation, remains silent on the concept of a Creator God, focusing instead on the mechanistic laws of cause and effect (Kamma) and the cessation of suffering. Islam, conversely, is predicated entirely on the absolute Oneness of God (Tawhid) and the human obligation to worship. Yet, when one descends from the abstract heights of metaphysics to the lived reality of the human condition, a startling convergence emerges. Both traditions approach the human being as a spiritual entity in crisis—ailing, distracted, and in desperate need of a cure.

The Buddha famously presented himself not as a god, but as a physician (Bhisakka). His Four Noble Truths follow the ancient Indian medical formula: diagnosis of the disease, identification of the pathogen, prognosis of cure, and prescription of the remedy. Similarly, the Qur’an describes itself as a “healing for what is in the breasts” (shifa’un lima fi al-sudur) and a guide out of darkness into light. The Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) is often depicted in the role of a spiritual doctor, and the vast tradition of Islamic psychology (Ilm al-Nafs) treats vices as diseases (Amrad al-Qalb) requiring specific treatments.

This report leverages this shared medical framework to conduct a deep comparative analysis. By mapping the Four Noble Truths against Islamic theology, we move beyond superficial similarities to understand how each tradition addresses the fundamental problem of Dukkha or Kabad—the inherent unsatisfactoriness of unexamined life. We will explore how the Buddhist diagnosis of craving (Tanha) mirrors the Islamic diagnosis of caprice (Hawa); how the cessation of suffering (Nirodha) finds echoes in the Sufi concept of Annihilation (Fana) and the Qur’anic promise of the Reassured Soul (Nafs al-Mutma’innah); and how the Noble Eightfold Path offers a structural template that aligns with the Islamic Sharia and the spiritual stations (Maqamat) of the Sirat al-Mustaqim.

Through this extensive exploration, encompassing textual evidence from the Pali Canon and the Qur’an, as well as the insights of scholars like Al-Ghazali and Ibn Qayyim, we aim to provide a nuanced understanding of how two of the world’s great wisdom traditions guide humanity from the turbulence of suffering to the sanctuary of peace.

The First Noble Truth: The Diagnosis of Existence

The Buddhist Reality: Dukkha Ariyasacca

The First Noble Truth constitutes the foundational diagnosis of the Buddhist worldview: “Now this, bhikkhus, is the noble truth of suffering: birth is suffering, aging is suffering, illness is suffering, death is suffering; union with what is displeasing is suffering; separation from what is pleasing is suffering; not to get what one wants is suffering; in brief, the five aggregates subject to clinging are suffering”.1

The Pali term Dukkha is frequently mistranslated simply as “suffering,” which suggests physical pain or acute emotional distress. However, the etymology—often linked to a wheel with an off-center axle—implies a fundamental disjointedness, an unsatisfactoriness, or a pervasive sense of stress and friction. The Buddhist analysis decomposes Dukkha into three distinct ontological categories:

- Dukkha-dukkha (The Suffering of Suffering): This encompasses the obvious forms of physical and mental pain—trauma, injury, grief, and physical discomfort. It is the undeniable suffering inherent in having a biological body susceptible to disease and injury.2

- Viparinama-dukkha (The Suffering of Change): This is a more subtle realization that even pleasurable experiences are ultimately unsatisfactory because they are impermanent (Anicca). The anxiety of losing what one loves, or the inevitable fading of a joyful state, constitutes suffering. In Buddhism, happiness that is dependent on unstable conditions is merely a prelude to pain.3

- Sankhara-dukkha (The Suffering of Conditioned States): This is the most profound level, referring to the inherent instability of existence itself. Because the human being is a compound of five changing aggregates (form, feeling, perception, mental formations, consciousness), there is no stable core or “self” to find rest. The very fact of being constructed (Sankhata) means one is subject to deconstruction.2

The Buddha’s diagnosis is not pessimistic but realistic; it refuses to ignore the “marks of existence.” The First Truth demands that the practitioner comprehends suffering, rather than merely trying to avoid it.

The Islamic Parallel: Kabad, Bala, and the Abode of Trial

Islam accords with the Buddhist observation that life in this world is fundamentally fraught with hardship, though it frames this reality within a theistic and teleological structure. The Qur’an does not view the world as an illusion to be transcended but as a reality to be navigated, yet it is a reality defined by struggle.

The Concept of Kabad (Toil)

The most direct Qur’anic analogue to Dukkha is found in Surah Al-Balad:

“We have certainly created man into hardship (Kabad).” (Qur’an 90:4).6

The term Kabad implies intense labor, struggle, and exhaustion. Classical commentators provide a comprehensive exegesis of this term that mirrors the scope of Dukkha. Ibn Kathir interprets it as man being created in “travail,” dealing with the tribulations of the world and the anxieties of the Hereafter.6 The exegete Al-Qurtubi explains that man endures the darkness of the womb, the pain of birth, the struggle for sustenance, and the trials of death. Syed Abu-al-A’la Maududi elaborates that this “toil” is universal: “Even if he is a king or a dictator, he at no time enjoys internal peace… Thus, there is no one who may be enjoying perfect peace freely and without hesitation, for man indeed has been created into a life of toil and trouble”.6 This aligns perfectly with the Buddhist assertion that suffering permeates all strata of existence, from the pauper to the emperor.

The World as Dar al-Bala (Abode of Trial)

While Buddhism sees suffering as a result of ignorant causal conditioning, Islam sees it as a deliberate feature of Divine design. The world is often termed Dar al-Bala.

“Who created death and life in order to test you (Li-yabluwakum) which of you is best in deeds.” (Qur’an 67:2).7

Here, the suffering is purposeful. It is a mechanism of examination. The term Bala (trial/test) appears frequently to describe the inevitable hardships of life.

“We will surely test you through some fear, hunger, and loss of money, lives, and crops.” (Qur’an 2:155).8

This verse enumerates specific forms of Dukkha-dukkha—physical deprivation, loss of loved ones, and economic hardship—confirming them as unavoidable aspects of the human experience decreed by God.

Fitnah and the Suffering of Change

The Buddhist concept of Viparinama-dukkha (suffering of change) finds resonance in the Islamic concept of Fitnah (tribulation/temptation). The Qur’an warns:

“Your money and children are a test (Fitnah).” (Qur’an 64:15).8

In this context, the things human beings cling to—wealth and family—are identified not as sources of ultimate security, but as trials. They are impermanent and can be sources of deep anxiety and spiritual diversion. The “suffering of change” is inherent here; the loss of wealth or the rebellion of a child causes pain precisely because of the attachment formed to them. Islam teaches that attachment to the Dunya (temporal world) leads to suffering because the Dunya is by nature fleeting (Fani).

Comparative Synthesis: Purpose vs. Process

The divergence between the two traditions lies not in the fact of suffering, but in its interpretation.

For the Buddhist, Dukkha is a mark of a broken system (Samsara) driven by blind ignorance. There is no punisher and no tester; there is only the grinding wheel of cause and effect. The goal is to step off the wheel.

For the Muslim, suffering is an instrument of Tarbiyah (Divine nurturing). It serves to expiate sins, elevate spiritual rank, and distinguish true believers from hypocrites.9 The Prophet Muhammad said, “No fatigue, nor disease, nor sorrow, nor sadness, nor hurt, nor distress befalls a Muslim, even if it were the prick he receives from a thorn, but that Allah expiates some of his sins for that.” This transforms suffering from a meaningless structural defect into a redemptive opportunity.

However, phenomenologically, the experience is identical. Both the Buddhist practitioner and the Muslim believer are trained to look at the world and see its inherent lack of satisfaction. They are both taught that seeking ultimate peace in the changing phenomena of the world is a fool’s errand. As the research indicates, “Conquest of suffering/ignorance is what religion proposes as its task and both Islam and Buddhism are in perfect agreement over this issue”.10

The Second Noble Truth: The Etiology of Suffering

The Buddhist Cause: Tanha and Upadana

The Second Noble Truth (Dukkha Samudaya) identifies the origin of suffering as Tanha (craving or thirst). This is not merely the desire for necessities, but a neurotic, ego-driven compulsion that drives the cycle of becoming.

“It is this craving which leads to renewed existence, accompanied by delight and lust, seeking delight here and there; that is, craving for sensual pleasures, craving for existence, craving for extermination”.3

Buddhism categorizes Tanha into three streams:

- Kama-tanha: Craving for sense pleasures (food, sex, comfort).

- Bhava-tanha: Craving for existence and becoming (desire for fame, immortality, or distinct identity).

- Vibhava-tanha: Craving for non-existence (desire to annihilate oneself to escape pain).

This craving feeds Upadana (clinging). The mind clings to the Five Aggregates, solidifying the delusion of a permanent “Self” (Atta). This clinging is the fuel for Samsara. The root of this entire causal chain is Avijja (Ignorance)—specifically, ignorance of the Four Noble Truths and the Three Marks of Existence (Anicca, Dukkha, Anatta).2

The Islamic Cause: Hawa and the Diseases of the Heart

Islam offers a strikingly similar diagnosis of the internal human condition, locating the source of spiritual and existential malaise in the unchecked desires of the Nafs (the lower self or soul). While Islam posits the existence of a soul (unlike the Buddhist Anatta), it argues that this soul is prone to diseases caused by desire.

Hawa (Caprice) as the Root of Ruin

The term Hawa refers to the inclination of the soul towards that which pleases it immediately, often in contradiction to reason and Divine guidance. It is the Islamic equivalent of Tanha. The Qur’an issues a stark warning:

“Have you seen the one who takes as his god his own desire (Hawa)?” (Qur’an 25:43).11

Here, following one’s craving is equated to idolatry (Shirk). Just as Tanha traps the Buddhist in Samsara, Hawa traps the Muslim in the material world, blinding them to spiritual truth. Classical scholar Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyyah asserts, “All diseases of the heart can be reduced to following desires”.12 He argues that when a person prioritizes their immediate cravings over what is beneficial (the Divine Law), they create a state of internal corruption.

Shahwah (Appetite) and the Al-Ghazali Diagnosis

The great theologian Abu Hamid al-Ghazali provides a detailed taxonomy of desire in his Ihya Ulum al-Din, specifically in the book Kitab Kasr al-Shahwatayn (“Breaking the Two Desires”). He identifies two primal appetites as the root of all human suffering:

- The Desire of the Stomach (Shahwat al-Batn): Ghazali argues that gluttony is the progenitor of all other vices. It increases the blood and libido, leading to the second desire.13

- The Desire of the Genitals (Shahwat al-Farj): The energy generated by food seeks release through sexual lust.

Ghazali traces a causal chain remarkably similar to the Buddhist Paticcasamuppada:

- Gluttony leads to Lust.

- Lust leads to the desire for Wealth (Mal) and Status (Jah) to satisfy these lusts.

- The desire for Wealth and Status leads to Rivalry, Envy (Hasad), and Ostentation (Riya).

- These social vices lead to conflict, oppression, and spiritual ruin.13

This analysis mirrors the Buddhist teaching that Tanha leads to Upadana (clinging to worldly conditions) and Bhava (becoming/ego-assertion).

Hubb al-Dunya (Love of the World)

The Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) stated, “Love of the world is the root of every sin.” This concept of Hubb al-Dunya encapsulates attachment to the transient. It is the Islamic equivalent of clinging to the aggregates. Ibn Ata Allah al-Iskandari, a Sufi sage, writes: “How can the heart be illumined while the forms of creatures are reflected in its mirror? Or how can it journey to God while shackled by its passions?”.11 This rhetorical question highlights that attachment acts as a fetter, preventing liberation.

Table 1: The Pathology of Desire in Buddhism and Islam

| Feature | Buddhism (Tanha/Upadana) | Islam (Hawa/Shahwah) |

| Primary Driver | Craving (Tanha) for sense pleasure and existence. | Caprice (Hawa) and Lust (Shahwah) of the Nafs. |

| Mechanism | Craving leads to Clinging (Upadana) to Aggregates. | Love of World (Hubb al-Dunya) leads to Heedlessness (Ghafla). |

| Root Cause | Ignorance (Avijja) of the 4 Truths. | Ignorance (Jahl) of God and the Afterlife. |

| Consequence | Rebirth in Samsara (Jati/Jara-marana). | Spiritual Death of the Heart (Mawt al-Qalb) and Hellfire. |

| Nature of Trap | Illusion of a permanent Self (Atta). | Illusion of autonomy and permanence of the World. |

Comparative Insight: The “Self” as the Problem

A critical nuance arises in how the “Self” is viewed as the problem.

In Buddhism, the belief in a self (Sakkaya-ditthi) is the primary delusion. The cure is to see through the illusion of the self (Anatta).

In Islam, the Nafs (soul/self) is a reality, but it exists in different states. The Nafs al-Ammarah (The Commanding Soul) is the enemy within that incites evil.14 The cure is not to realize the self doesn’t exist, but to discipline and purify it until it becomes Nafs al-Lawwamah (The Self-Reproaching Soul) and finally Nafs al-Mutma’innah (The Reassured Soul).

Despite this ontological difference, the functional asceticism is identical: both traditions demand a rigorous war against the ego’s impulses. As Ibn Qayyim writes, “The servant of Allah who seeks the pleasure of Allah never abandons tawbah (repentance)” and must constantly oppose their desires to avoid being “taken captive by his enemy”.12

The Third Noble Truth: The Cessation of Suffering

The Buddhist Goal: Nirodha and Nirvana

The Third Noble Truth (Dukkha Nirodha) declares that the cessation of suffering is possible. This cessation is Nirvana (Pali: Nibbana), which literally means “blowing out”—extinguishing the fires of greed, hatred, and delusion.

“It is the complete fading away and cessation of that very craving, its giving up and relinquishing, freedom from it, non-reliance on it”.3

Nirvana is the “Unconditioned” (Asankhata). It is not a place, but a reality experienced when the causes of suffering are removed. It is described apophatically:

- Deathless (Amata)

- Birthless (Ajata)

- Ageless (Ajara)

- Sorrowless (Asoka).4

It is the end of the cycle of rebirth. The one who attains it (the Arahant) has completed the holy life; “birth is destroyed, the holy life has been lived, what had to be done has been done.”

The Islamic Goal: Falah, Jannah, and Fana

Islam offers a multi-layered soteriology that corresponds to the cessation of suffering in different dimensions.

Jannah (Paradise): The Abode of Ultimate Cessation

The most apparent equivalent to Nirvana—in terms of the end of suffering—is Jannah (Paradise). The Qur’an explicitly defines it as a realm where negative states are negated:

“No fatigue will touch them therein, nor will they be expelled from it.” (Qur’an 15:48).

“They will not hear therein any ill speech or commission of sin – Only a saying: ‘Peace, Peace’ (Salam, Salam).” (Qur’an 56:25-26).

In Jannah, the struggle (Kabad) of life ends. The trial (Bala) is over. The “thirst” of the human soul is quenched, quite literally, by rivers of milk, honey, and wine that does not intoxicate.15 However, unlike Nirvana, which is often associated with the cessation of sensory becoming, Jannah is a realm of sanctified sensory and spiritual fulfillment. It is the “affirmation” of existence in its highest form, rather than the “cessation” of becoming.

Fana (Annihilation): The Mystical Cessation

In the esoteric tradition of Islam (Sufism), the concept of Fana bears a profound phenomenological resemblance to Nirvana. Fana means “extinction” or “annihilation.” It refers to the passing away of the limited, egoic self in the overwhelming presence of the Divine Reality (Al-Haqq).

Sufi scholars like Al-Ghazali and Al-Kalabadhi describe Fana as the state where the mystic loses all awareness of themselves and the created world, seeing only God.16

- Fana of Attributes: The mystic’s human attributes are replaced by the reflection of Divine attributes.

- Fana of Essence: The complete absorption where the “I” vanishes.

This maps closely to the Buddhist realization of Anatta (No-Self). Just as the Buddhist realizes the emptiness (Sunyata) of the self, the Sufi realizes the nullity of the self before the Absolute. However, Fana is followed by Baqa (Subsistence)—returning to the world with a transformed consciousness, subsisting in God. This mirrors the Mahayana concept of the Bodhisattva who returns to the world of Samsara with the wisdom of Nirvana.

Rida (Contentment): Cessation in This Life

Before the afterlife, Islam teaches that suffering can be transcended psychologically through the station of Rida (Contentment).

Ibn Qayyim explains that Rida is the “Paradise of the World” (Jannah al-Dunya). When a believer is fully content with God’s decree, the sting of suffering is removed.

“It is to be content with all that Allah has decided… that all conditions [calamity or bounty] become the same to the servant”.18

This state of equanimity, where pain and pleasure are viewed with equal detachment, strongly parallels the equanimity (Upekkha) of the Buddhist saint.

Comparative Insight: The Agency of Salvation

A critical theological divergence exists regarding how cessation is achieved.

- Buddhism (Theravada): Salvation is self-reliant. “You yourselves must strive; the Buddhas only point the way” (Dhammapada). No god can purify another; the practitioner must liberate themselves through their own effort (Viriya).4

- Islam: Salvation is a synergy of human effort and Divine Grace. The Qur’an emphasizes Tawakkul (trust/reliance on God). The Prophet said, “None of you will enter Paradise by his deeds alone… unless Allah covers me with His Mercy”.5

- Synthesis: Interestingly, Pure Land Buddhism (Mahayana) introduces the concept of Tariki (Other-power), relying on Amitabha Buddha’s vow, which brings it much closer to the Islamic concept of reliance on Grace (Rahma).5

The Fourth Noble Truth: The Path to Cessation

The Fourth Noble Truth (Dukkha Nirodha Gamini Patipada) is the Noble Eightfold Path. This is the practical methodology of Buddhism. Islam describes its path as Sirat al-Mustaqim (The Straight Path) and Sharia (The Divine Law). When we dissect the Eightfold Path, we find that every factor has a direct, and often rigorous, equivalent in Islamic practice.

The Eightfold Path is divided into three trainings: Wisdom (Panna), Ethical Conduct (Sila), and Mental Discipline (Samadhi).

I. The Training in Wisdom (Panna)

1. Right View (Samma Ditthi) vs. Iman and Tawhid

Right View is the correct understanding of reality—specifically the Four Noble Truths, the law of Kamma, and the Three Marks of Existence.19 It is the compass that orients the practitioner.

Islamic Parallel: Iman (Faith) and Tawhid (Oneness of God). For a Muslim, “Right View” is the recognition that there is no god but Allah and that Muhammad is His messenger. This worldview dictates that the world is a creation, a test, and a passage to the Hereafter. Just as Right View breaks the delusion of permanence in Buddhism, Tawhid breaks the delusion of independent power in creation—seeing God as the sole Cause (Musabbib al-Asbab).20

- Contrast: Buddhist Right View sees “No Creator.” Islamic Right View sees “Only Creator.” Yet functionally, both serve as the cognitive foundation for ethical restraint.

2. Right Intention (Samma Sankappa) vs. Niyyah and Ikhlas

Right Intention involves thoughts of renunciation (Nekkhamma), non-ill will (Abyapada), and harmlessness (Avihimsa).21 It is the mental resolve to practice.

Islamic Parallel: Niyyah (Intention). The famous Hadith states: “Actions are judged by intentions.” An action performed without the right intention is spiritually void.

- Ikhlas (Sincerity): This is the purification of intention, ensuring deeds are done solely for God’s pleasure, free from Riya (showing off). This mirrors the Buddhist “renunciation” of ego-centric motives. Ibn Qayyim emphasizes that without Ikhlas, the heart remains sick.22

II. The Training in Ethical Conduct (Sila)

3. Right Speech (Samma Vaca) vs. Hifz al-Lisan

Right Speech entails abstaining from lying, divisive speech, harsh words, and idle chatter.23

Islamic Parallel: Hifz al-Lisan (Guarding the Tongue). The Qur’an and Sunnah are extremely strict regarding speech.

- Lying: Strictly forbidden.

- Backbiting (Ghibah): Described in the Qur’an as eating the flesh of a dead brother (49:12), a vivid metaphor for the harm of divisive speech.

- Idle Chatter: Islam discourages Laghw (vain talk). The Prophet said, “From the perfection of a person’s Islam is his leaving that which does not concern him.” Al-Ghazali dedicates an entire book of the Ihya to the “Evils of the Tongue,” prescribing silence as a discipline.24

4. Right Action (Samma Kammanta) vs. Amal Salih

Right Action is abstaining from killing, stealing, and sexual misconduct.25

Islamic Parallel: Amal Salih (Righteous Deeds) and adherence to the Halal (permissible) and Haram (forbidden).

- Killing: The Qur’an states that killing one innocent soul is like killing all of humanity (5:32).

- Stealing: Explicitly punished and forbidden.

- Sexual Misconduct: Zina (adultery/fornication) is a major sin. Islam goes further by prohibiting the steps leading to it, such as the command to “lower the gaze” (24:30), creating a preventative “sense-restraint” similar to monastic discipline.26

5. Right Livelihood (Samma Ajiva) vs. Kasb Halal

Right Livelihood prohibits five specific trades: weapons, human beings (slavery), meat/slaughter, intoxicants, and poisons.4

Islamic Parallel: Kasb Halal (Lawful Earning). Islam has a comprehensive economic code prohibiting income from:

- Intoxicants (Khamr): Manufacturing, selling, or transporting alcohol/drugs is cursed.

- Usury (Riba): Dealing in interest is considered a war against God.

- Gambling (Maysir).

- Pork and Idols: Selling forbidden items is forbidden.Insight: Both traditions recognize that one’s economic life is not separate from spiritual life. “Wrong Livelihood” pollutes the mind and prevents spiritual progress (or the acceptance of Dua in Islam).28

III. The Training in Mental Discipline (Samadhi)

6. Right Effort (Samma Vayama) vs. Mujahada

Right Effort is the exertion to prevent and abandon unwholesome states, and to arouse and maintain wholesome states.29

Islamic Parallel: Mujahada (Struggle) and Jihad al-Nafs (Struggle against the Self). The Prophet distinguished the physical battle as “Lesser Jihad” and the internal struggle as “Greater Jihad.”

- Ibn Qayyim describes the mechanism of sin: It starts as a fleeting thought (Khatira). If not repelled (Right Effort), it becomes an idea (Fikra), then a desire (Shahwah), then a resolve (Azm), and finally an action. The spiritual warrior must stand guard at the gate of thoughts, exactly as prescribed in Buddhist mental training.12

7. Right Mindfulness (Samma Sati) vs. Muraqabah

Right Mindfulness is continuous awareness of the body, feelings, mind, and mental objects.31

Islamic Parallel: Muraqabah (Watchfulness). The Sufi practice of maintaining a continuous awareness of God’s presence. The root Ra-Qa-Ba means to watch or guard.

- Dhikr (Remembrance): The practice of repeating God’s names to anchor the mind. While Buddhist mindfulness is often “open monitoring,” Dhikr is “focused attention,” but the result—liberation from heedlessness (Ghafla)—is similar.32

- Taqwa (God-Consciousness): A state of constant vigilance where the believer is “mindful” of God in every action, ensuring it aligns with the Divine pleasure.

8. Right Concentration (Samma Samadhi) vs. Khushu and Ihsan

Right Concentration refers to the Jhanas, states of deep absorption and unification of mind.33

Islamic Parallel:

- Khushu: The deep, stillness and humility experienced in Salah (prayer). “Successful are the believers who are humble (Khashi’un) in their prayers” (Qur’an 23:1-2).

- Hudur al-Qalb: Presence of heart.

- Ihsan (Excellence): The Prophet defined Ihsan as “To worship Allah as if you see Him, and if you do not see Him, know that He sees you”.32 This denotes a state of total absorptive focus, similar to the one-pointedness (Ekaggata) of Samadhi.

Table 2: The Noble Eightfold Path vs. The Straight Path (Sirat al-Mustaqim)

| Noble Eightfold Path | Islamic Equivalent | Concept / Practice |

| Right View | Iman / Tawhid | Belief in One God and the Reality of the Hereafter. |

| Right Intention | Niyyah / Ikhlas | Sincere intention for God; purification of motive. |

| Right Speech | Hifz al-Lisan | Guarding the tongue; avoiding lying and backbiting. |

| Right Action | Amal Salih / Halal | Adherence to Sharia; avoiding Zina, theft, killing. |

| Right Livelihood | Kasb Halal | Earning without Riba, Alcohol, or Gambling. |

| Right Effort | Mujahada / Jihad al-Nafs | Struggling against the lower desires of the Soul. |

| Right Mindfulness | Muraqabah / Taqwa | Vigilance over the heart; God-consciousness. |

| Right Concentration | Khushu / Ihsan | Deep absorption and presence in worship/prayer. |

Deep Dive: The Classical “Cure” Manuals

To fully appreciate the depth of these parallels, one must look at the “medical manuals” produced by the scholars of both traditions.

Al-Ghazali’s Kitab Riyadat al-Nafs (Disciplining the Soul)

Al-Ghazali (d. 1111) is often called the “Proof of Islam.” In his magnum opus, Ihya Ulum al-Din, he presents a systematic method for curing the soul that rivals the Visuddhimagga in detail.

He argues that the soul is trainable, like a wild horse. He prescribes four primary disciplines (the “Breakers”):

- Hunger (Jū’): To break the greed of the stomach and soften the heart.

- Vigil (Sahar): Staying awake at night for prayer to break sloth and illuminate the heart.

- Silence (Samt): To break the sins of the tongue.

- Solitude (Khalwah): To break the desire for fame and social approval.34This regimen is strikingly similar to the Dhutanga (ascetic practices) of the Buddhist Forest Tradition, designed to “efface” the defilements.

Ibn Qayyim’s Madarij al-Salikin (Stages of the Seekers)

Ibn Qayyim (d. 1350) maps the spiritual journey as a series of stations (Manazil). He asserts that the health of the heart is fundamental.

- Preventative Medicine: He advises guarding the “Four Gates” to the heart: Glances, Thoughts, Words, and Steps.

- Curative Medicine: For a heart already sick with desire, he prescribes Tawbah (Repentance), Inabah (Turning back to God), and Muhasabah (Self-accounting).He writes: “If a person were to pay close attention to the physical diseases they would find that the majority of them come from preferring desires over what is meant to be avoided”.12 His approach is cognitive-behavioral, focusing on intercepting thoughts before they become actions.

Thematic Epilogue: The Universal Search for Peace

The ultimate convergence of Buddhism and Islam lies in their shared etymological and teleological orientation towards Peace.

In Buddhism, Nibbana is often equated with Santi (Peace)—the supreme happiness (Natthi santi param sukham). This peace is the coolness resulting from the extinguishing of the fires of agitation. It is a peace from the world—a transcendence of the conditioned.

In Islam, God is As-Salam (The Source of Peace). The greeting of the believer is Salam. Paradise is Dar as-Salam (The Abode of Peace). This peace is the tranquility (Sakina) resulting from the surrender of the will to the Divine Will. It is a peace with the Reality—a reconciliation with the Creator.

While the Buddhist seeks to deconstruct the self to remove the target of suffering, the Muslim seeks to submit the self to the Owner of suffering. The Buddhist path is one of Discovery—waking up to the true nature of reality (Anatta, Anicca). The Islamic path is one of Recovery—returning to the primordial disposition (Fitra) and the covenant with God.

Yet, in the crucible of practice—in the silence of the meditation hall or the hush of the mosque before dawn—the phenomenology of the practitioner converges. Both are engaged in a fierce, disciplined struggle against the gravity of the ego, guarding their senses, watching their thoughts, and aspiring toward a reality that transcends the fleeting, unsatisfactory nature of the material world. In an age of distraction and materialism, both the Four Noble Truths and the Qur’anic revelation stand as monumental testaments to the human capacity to transcend suffering through discipline, wisdom, and the purification of the heart.

Read in PDF file:

Leave a comment