Presented by Zia H Shah, the Chief Editor of the Muslim Times

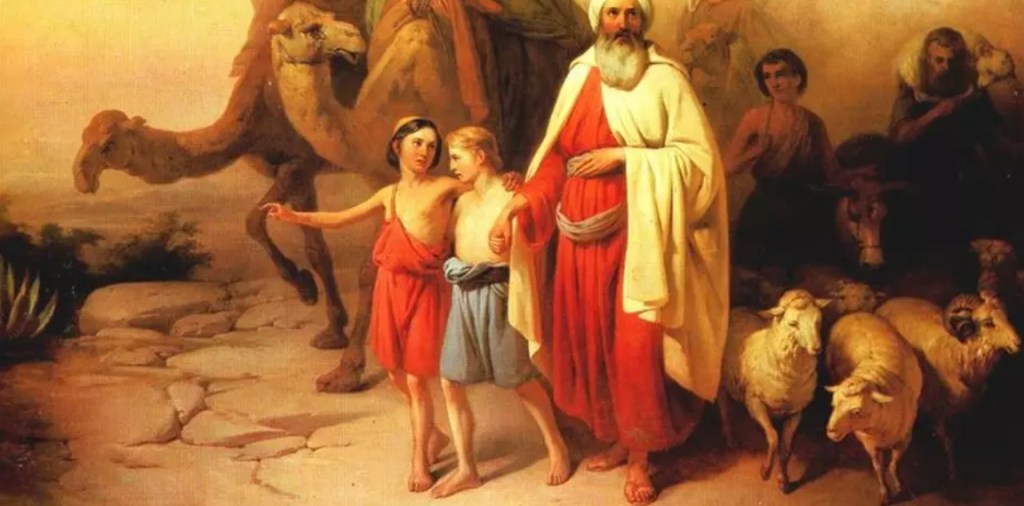

Scriptural Accounts of Joseph and the Ishmaelites

In the Hebrew Bible the story of Joseph and the Ishmaelites appears in Genesis 37. After Joseph’s brothers threw him into a pit, Genesis 37:25–28 reports: “They sat down to eat, and looking up they saw a caravan of Ishmaelites coming from Gilead… Then Judah said, ‘What profit is it if we kill our brother and cover his blood? Let us sell him to the Ishmaelites…’ So they drew Joseph up out of the pit and sold him for twenty shekels of silver to the Ishmaelites; and the Ishmaelites took Joseph to Egypt”bible.oremus.org. In this account the merchants are explicitly called “Ishmaelites”, son of Abraham’s firstborn (verses 25–28). Notably, they are on a commercial caravan bound for Egypt, and they rescue Joseph from starvation only to sell him into slavery. Genesis thus names the captors as descendants of Abraham (via Ishmael) who unwittingly further God’s plan for Israel’s exile in Egypt.

The Qur’an gives a parallel narrative in Surah 12 (Yusuf). It states that after Joseph is set in the well, “a caravan came, and they sent their water-drawer, who let down his bucket. He cried, ‘Good news! Here is a young boy!’” quran.com. They hide Joseph as merchandise and sell him for a paltry price corpus.quran.com. Though the Qur’an never by name says “Ishmaelites,” its account clearly echoes the Genesis motif of a foreign caravan finding Joseph in the pit. In one English rendering, the Qur’an 12:19–20 reads: “Behold, there came a company of travelers; they sent their water-drawer, and he let down his bucket into the well. He said, ‘Good news! Here is a boy!’ And they sold him for a paltry price, a handful of counted dirhams…” corpus.quran.com. Thus both scriptures describe Joseph’s delivery by desert traders (descendants of Abraham’s family) after the brothers’ conspiracy, setting him on the path to Egypt.

Scholarly and Theological Commentary on Joseph’s Rescue

Religious commentators see this rescue as providential. Classic Christian expositors note that God overrules human malice for a higher purpose. Matthew Henry writes that though the brothers intended evil, “the wrath of man shall praise God, and the remainder of wrath he will restrain”, remarking that their selling Joseph was “wonderfully turned to God’s praise” biblehub.com. Commentator Albert Barnes observes that by selling Joseph to Abraham’s kin, Joseph “is sold to the descendants of Abraham,” implying even this tragedy keeps him within God’s Abrahamic family biblehub.com. In other words, early interpreters recognized that Joseph (Jacob’s son) ends up in the hands of fellow Abraham-descendants (Ishmaelites/Midianites), foreshadowing later reconciliation.

Islamic scholars likewise emphasize God’s hand in the event. Tafsir Jamaluddin al-Maududi notes that the Qur’an’s simplicity (“the brothers threw Joseph in the well and a caravan came and carried him to Egypt”) contrasts with the Bible’s more tangled account alim.org. He points out that, according to the Qur’an, only God truly knows their deeds – the Ishmaelite caravan unknowingly enacts God’s will. Maududi emphasizes that unlike some Talmudic traditions, the Qur’an does not state the brothers sold Joseph directly; it simply records the caravan finding him alim.org. Thus commentators often read the episode as a demonstration of divine providence: human sin (jealousy, betrayal) is outwitted by God’s plan to elevate Joseph. In all traditions, Joseph’s rescue is seen as part of a covenant unfolding – the “selling” incident ultimately preserves Jacob’s lineage (via Joseph in Egypt) and spreads Abraham’s blessings beyond Israel.

Ishmael in Islamic Tradition: Genealogy and Theology

In Islamic faith, Ishmael (Ismāʿīl) is a prophet and a patriarch. The Qur’an repeatedly affirms Ishmael’s virtue: “And mention in the Book Ishmael: he was true to his promise, and he was a messenger and a prophet” (19:54)quran.com. Ishmael is honored as Abraham’s firstborn son. Abraham’s own prayer includes Ishmael: “All praise is due to Allah who has granted to me in old age Ishmael and Isaac…” (Ibrahim 14:39)quran.com. Moreover, Islamic tradition holds that Abraham and Ishmael together built the Kaaba in Mecca, as the Qur’an relates: “And remember Abraham and Ishmael raising the foundations of the House (Kaaba)…” (2:127)corpus.quran.com. This joint act underlines Ishmael’s central place in Islam as forefather of Arab peoples and ally of Abraham.

Genealogically, Genesis also credits Ishmael with founding a great nation. God’s promise to Abraham says, “As for Ishmael… I will multiply him exceedingly; he shall become the father of twelve princes, and I will make him into a great nation” (Gen. 17:20)biblehub.com. Genesis 25:12–16 then lists twelve sons of Ishmael (Nebaioth, Kedar, Adbeel, etc.)biblehub.com. Many Muslims view these twelve clans as ancestral to Arab tribes. Traditional lineages often trace the Prophet Muhammad’s ancestry through either Kedar or Nebaioth (Ishmael’s son)en.wikipedia.org. The Ishmaelite tribes became known for commerce (the caravan traders) and spread into northern Arabia. The Qur’an’s positive treatment of Ishmael – as a rightful heir of Abraham’s message – contrasts with Jewish tradition which focused on Isaac’s line. Nonetheless, both Abrahamic lineages are blessed: Islam acknowledges Ishmael’s prophetic role and nationhood, while Genesis affirms the parallel promise through Isaac and Jacob.

The Twelve Tribes of Israel in Judaism and Christianity

In Judaism the Twelve Tribes of Israel descend from Jacob (Israel) through his twelve sons (Genesis 35:22–26; 49). These tribes are the foundation of the Israelite nation in the Torah. Jacob’s deathbed blessings (Genesis 49) enumerate them (e.g. Judah, Joseph, etc.) and promise future fortunes. Moses likewise blesses Israel’s leaders (Deuteronomy 33) in terms of tribal names. Jewish tradition maintains that these tribal identities governed land allotments and heritage in biblical Israel. Genesis itself notes that Ishmael’s “twelve princes” mirror Jacob’s twelve tribes, but the covenant promises (land, Messiah) pass through Isaac and Jacoben.wikipedia.org.

Christian scripture also draws on the Twelve Tribes. In the Gospels Jesus tells his disciples they will “sit on twelve thrones, judging the twelve tribes of Israel” in the Kingdom (Matthew 19:28; Luke 22:30)en.wikipedia.org, indicating continuity with Israel’s heritage. The author of James addresses “the twelve tribes which are scattered abroad” (James 1:1)en.wikipedia.org, using the tribal metaphor for his Jewish-Christian audience. The Revelation to John lists the names of all the tribes (sometimes adding Joseph and Manasseh, omitting Dan) on the New Jerusalem’s gatesen.wikipedia.org, symbolizing the inclusion of all Israel in the vision of God’s people. Thus Christian tradition sees the twelve-tribe motif carried forward in the Church’s identity and eschatology. In sum, both Judaism and Christianity view the twelve sons of Jacob as spiritually primary: Israel’s twelve tribes form the bedrock of the biblical community, a heritage explicitly invoked by Jesus and the apostles en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org.

Symbolism and Interfaith Implications of the Rescue

Joseph’s rescue by “Ishmaelites” has been seen as symbolically rich for Abrahamic unity. On one level, the story itself joins together Abraham’s two lines. A believer might observe: Abraham’s elder son’s descendants (the Ishmaelites) save Abraham’s younger son’s son (Joseph), who then becomes a savior for Israel (through famine relief). Early commentators point out that Joseph is effectively sold “to the descendants of Abraham”, whether through Midian or Ishmael biblehub.com, underlining that even betrayal by kin stayed within the Abrahamic family.

Theologically, many scholars read this as a foreshadowing: all branches of Abraham’s family cooperate under God’s plan. For example, Barnes notes that Joseph’s captors were from Abraham’s extended family, making the traumatic sale part of a larger divine design biblehub.com. In modern interfaith reflection, some treat Joseph as a bridge-figure: he is a prophet honored in Judaism, Christianity and Islam, and his deliverance is achieved by another Abrahamic branch. Although few early sources explicitly draw this metaphor, the narrative invites it. Jewish and Christian writers have often praised Ishmaelites’ unknowing role in preserving Israel; similarly, Muslim tradition sees Yahweh’s hand in allowing Abraham’s house to aid itself.

The broader Abrahamic unity theme is echoed in scripture: the Qur’an declares that the people most worthy of Abraham are his true followers (which, in Muslim view, includes all monotheistic believers)tikvah.org. Likewise, Paul the Apostle calls Abraham “the father of all who believe” (Romans 4:11) and Jesus and New Testament writers effectively enlarge “Israel” to include all the faithful across traditions. In this spirit, Joseph’s rescue can be interpreted as a metaphor for mutual dependence: the three faiths, all tracing lineage to Abraham, ultimately rely on one another’s spiritual heritage. Joseph (an Israelite) is sustained by “Ishmaelites” (Abraham’s other line), suggesting that Judaism, Christianity, and Islam are interconnected.

In conclusion, the story of Joseph and the Ishmaelites is more than a historical episode; it carries theological weight about Providence and kinship. Scripture presents it with few details, but commentators fill in meaning: that even human treachery serves God’s purposes, that Ishmael’s descendants play a role in Jacob’s destiny, and that the children of Abraham can be instruments for each other’s salvation. Seen through an interfaith lens, Joseph’s rescue is a vivid symbol that Abraham’s children – Jews, Christians and Muslims – share a common destiny and often an interwoven history. As one exposition notes, Joseph was “sold to the descendants of Abraham,” implying a bond that transcends the immediate rift biblehub.com. Thus the incident has been read as a parable of Abrahamic unity, showing that the fates of all three monotheistic communities are bound together from the very roots of their faithsbiblehub.comen.wikipedia.org.

Sources: Biblical passages from Genesis (37:24–28, 17:20, 25:13–15) and Qur’an 12:19–20, among others, document the event. Commentaries by Barnes, Matthew Henry, and modern Islamic exegetes (Maududi) elucidate its meaning biblehub.com alim.org. Scriptural references to Ishmael and the twelve tribes (Genesis and Qur’an) provide genealogical context biblehub.com quran.com quran.com en.wikipedia.org. Historical and theological interpretations (e.g. the “Abrahamic religions” motif) are discussed in scholarly sources to underline the shared heritage biblehub.com en.wikipedia.org.

Leave a comment