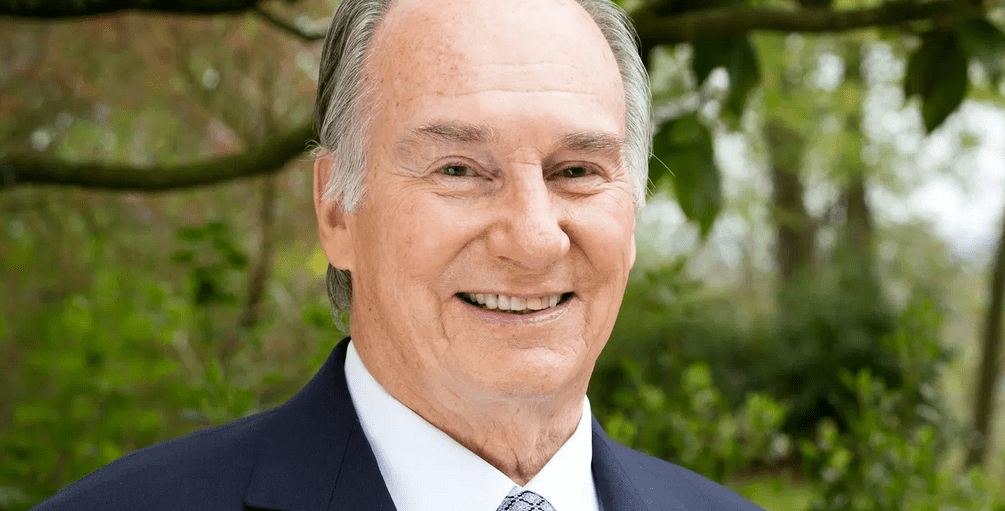

Presented by Zia H Shah MD

Introduction

In a recent lecture, an Ismaili scholar (Syed Aftab Hussain) offered an in-depth interpretation of the Islamic creed (shahāda) through the lens of Ismaili theology. The shahada – the declaration that “there is no deity except God, and Muhammad is His Messenger” – is affirmed by all Muslims as the foundational statement of faithismailimail.blog. However, as the scholar explains, the Ismaili understanding of this creed incorporates distinctive theological nuances and historical interpretations. Unlike Sunnis who count the shahada as the first of five pillars, Ismaili Muslims treat it as the fundamental foundation upon which their religious practice is built (rather than a numbered “pillar” itself)en.wikipedia.org. From the Ismaili perspective, the creed’s two clauses (God’s oneness and Muhammad’s messengerhood) are imbued with deeper, esoteric meanings that emphasize God’s absolute transcendence and the continuation of divine guidance through the line of Imams. The lecture thematically highlighted: (1) Tawḥīd (the oneness of God) as understood in Ismaili theology, (2) the role of prophethood and Imamate in the creed, and (3) points of distinction between Ismaili beliefs and those of Sunni and Twelver Shia traditions. Throughout, the scholar referenced doctrinal sources and historical events to support the Ismaili interpretation, situating it within the broader diversity of Islamic thought.

Tawḥīd and Divine Transcendence in Ismaili Theology

“Lā ilāha illā Allāh” (“there is no god but God”) – the first part of the creed – is interpreted by Ismaili theology in a highly philosophical and transcendent manner. The scholar stressed that Ismaili understanding of tawḥīd (divine oneness) “goes far beyond” a basic affirmation of monotheismismailignosis.com. In Ismaili thought, God is conceived as absolutely singular and transcendent in an unparalleled way. Several core theological arguments were emphasized:

- Absolute Unity of God: God is “absolutely one in all respects”, possessing no internal complexity or partitionismailignosis.com. This means that, unlike in some Sunni kalām doctrines which posit a set of eternal divine attributes (such as life, knowledge, power) distinct from God’s essence, Ismaili theology rejects any notion of multiple co-eternal attributes dwelling in Godismailignosis.com. God’s essence admits of no parts or plurality, a stance which underscores an uncompromising monotheism.

- No Created or Inherent Attributes: The Ismaili scholar underscored that God cannot be described as a sum of qualities. In line with classical Shia Ismaili teachings, God transcends all attributes – He does not possess attributes like knowledge or power as inherent qualities separate from Himselfismailignosis.com. This directly contrasts with the majority Sunni view that God does have eternal attributes (e.g. His Knowledge, Will, Speech, etc., conceived as pre-existent realities)ismailignosis.com. For Ismailis, saying “God is All-Knowing” or “All-Powerful” is acceptable only in a metonymic or metaphorical sense – for example, “All-Knowing” means God is the source of all knowledge, not that He harbors a definable attribute of knowledgeismailignosis.com. Any positive description of God is understood as human approximation, not a literal attribute of the divine, to avoid anthropomorphismismailignosis.com. The lecture highlighted this apophatic theology (via negativa), rooted in Ismaili philosophical tradition, which insists that God is beyond all earthly descriptions and conceptionismailignosis.com.

- God Beyond Being: Expanding on transcendence, the Ismaili perspective (as noted by the scholar) even characterizes God as beyond existence or non-existence as we understand themismailignosis.com. This radical transcendence means that God is not a being among beings; He is the Necessary Reality upon which all else depends, yet He is not limited by any category of being. In Ismaili Neoplatonic philosophy, God is often described as the ineffable origin, too exalted for attributes like “existing” or “not existing” to apply in a conventional senseismailignosis.comismailignosis.com. Such views set Ismaili tawḥīd apart as one of the most rigorous interpretations of divine unity in Islamismailignosis.com.

- Cosmological Doctrine (Intellect and Soul): The scholar also alluded to the Ismaili cosmological schema that emerges from this understanding of God’s oneness. Because God is absolutely transcendent and unchangeable, Ismaili doctrine holds that creation proceeds via a hierarchically ordered emanation. The First Intellect (al-ʿAql al-Awwal) is described as the first creation of God – a perfect, universal Intelligence through which all further creation flowsismailignosis.com. From this First Intellect emanates the Universal Soul, then the material world in descending order of perfectionismailignosis.com. By introducing this Neoplatonic cosmology, Ismaili theologians safeguard God’s purity: God Himself remains utterly beyond direct contact with the material realm, and creation is managed through these intermediary principles. While this was not a focus of Sunni creed, the Ismaili scholar used it to illustrate the depth of Ismaili theological interpretation of “no god but God”, showing how it entails a whole metaphysical worldview distinguishing Creator from creation.

Overall, the lecture’s treatment of lā ilāha illā Allāh emphasized divine transcendence and unity as understood in Ismailism. This interpretation has historically been supported by Ismaili philosophers and Imams. For example, medieval Ismaili works argued strenuously that God cannot be defined by attributes or even by existence, echoing early Shia Imams’ teachings that “whatever one conceives of God – He is other than that.” The scholar noted that this philosophical tawḥīd is a hallmark of Ismaili belief, setting it apart from more literalist or theologically moderate interpretations in other Muslim traditionsismailignosis.com.

Prophethood and Imamate in the Islamic Creed

The second part of the Islamic creed, “Muhammadun rasūlu’Llāh” (“Muhammad is the Messenger of God”), was discussed by the Ismaili scholar in tandem with the Shia notion of Imamate. In Ismaili theology, affirming Muhammad’s messengership carries an implication that extends beyond the Prophet’s lifetime: it includes acknowledging the line of spiritual authority that succeeds him. The scholar explained that accepting the Prophet Muhammad as the final messenger (Khātim al-Anbiyā’) goes hand-in-hand with recognizing the need for divinely guided leadership after him – a principle that gave rise to the Imamate in Shia Islamismailimail.blog.

According to Ismaili understanding, the Prophet explicitly designated ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib (his cousin and son-in-law) as his successor, most notably at Ghadīr Khumm in 632 CEismailimail.blog. This historical event – in which Muhammad is said to have declared, “Whomsoever I am the mawla (spiritual master) of, Ali is also his mawla” – is foundational for Shia doctrines. The scholar referenced such events to underscore that devotion to ʿAlī and his lineage is not a later innovation but originates in the Prophet’s own lifetimeismailimail.blog. Thus, for Ismailis, the Islamic creed implicitly encompasses walāya: devotion to God’s chosen heirs of Muhammad’s authority.

Walāya (Devotion to the Imam) was highlighted as a central concept. In fact, Ismaili Islam holds walāya to be the first and foremost pillar of the faith – the very principle that provides meaning to all other practiceschrishewer.org. Walāya signifies loving loyalty and allegiance to the Imam of the time, who is regarded as the rightful spiritual successor of the Prophet. The lecture noted that through the Imam’s guidance, believers attain the correct understanding of God and religionchrishewer.org. This idea distinguishes Ismailis: whereas Sunni Muslims ended the line of leadership with Muhammad (apart from temporal caliphs) and Twelver Shiʿa Muslims believe the line of Imams paused in the 9th century with an occultation, Ismailis affirm an unbroken chain of living Imams up to today. The current Imam (referred to in Nizārī Ismaili tradition as the Aga Khan IV) is considered the 49th hereditary Imam in direct descent from ʿAlī and Fāṭima, Prophet Muhammad’s daughterismailimail.blogismailimail.blog.

The scholar explained that the presence of a living Imam is a cornerstone of Ismaili creed and praxis. Each Imam is seen as the bearer of the nūr (light) of divine guidance, responsible for the spiritual interpretation of Islam in each age. This means that for Ismailis, guidance did not end with the Prophet – it continues via the Imams who illuminate the inner meaning of revelationchrishewer.org. Historically, after ʿAlī, a line of Imams (beginning with ʿAlī’s son Ḥasan or, in Ismaili reckoning, ʿAlī’s grandson through Ḥasan) led the community. The Ismaili scholar likely touched on the early schism in Shiʿism: upon the death of the sixth Imam Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq (d. 765), the community split – some followed his son Ismāʿīl (from whom Ismailis get their name), while others followed another son Mūsā al-Kāẓim (becoming the Ithnā ʿAshariyya or “Twelvers”)ismailimail.blog. The Ismailis continued with a living Imam in Ismāʿīl’s lineage, eventually establishing the Fatimid Caliphate, whereas the Twelvers’ line of Imams culminated in the 12th Imam who went into occultation in 874 CEismailimail.blog. This historical divergence solidified a major doctrinal difference: Ismailis today are unique in being led by a present, living Imam who actively guides the community, whereas Twelver Shiʿa await the future return of their hidden Imam (the Mahdi) and look to scholars for interim guidanceismailimail.blog.

In the context of the creed, therefore, “Muhammad is the Messenger of God” is understood in Ismailism as an acceptance not only of the Prophet’s message but also of the continuing authority of the Imams from his family to elucidate that message. The scholar emphasized that the Imam in Ismaili belief is not a prophet (since Muhammad is the final prophet) but the guardian and interpreter of prophecyismailimail.blog. The Imam is seen as endowed with divine guidance (though not bringing new scripture), ensuring the faith remains a living, guided tradition. This interpretation finds support in Ismaili literature and speeches of the Imams; for instance, it is often noted that the Imam’s role is to provide authoritative teaching (taʾwīl) of the revelation’s inner truths, just as the Prophet provided its outer formismailimail.blog. In summary, the scholar’s Ismaili perspective on the creed strongly links the testimony of God’s Oneness to the necessity of following God’s chosen guide – the Prophet and, by extension, the Imam who continues his mission. This is a key point of distinction from other Muslim interpretations of the creed.

Esoteric Interpretation and Inner Meaning

A recurring theme in the lecture was the importance of esoteric interpretation (taʾwīl) in Ismaili theology. The scholar noted that Ismailis distinguish between the ẓāhir (exoteric, outward form) and bāṭin (esoteric, inner truth) of religious teachingschrishewer.org. The Islamic creed itself can be understood on multiple levels. On the surface, all Muslims agree on the literal words of the shahada. But in Ismaili thought, the deeper spiritual truths behind those words are accessible through the guidance of the Imam and the use of intellect. For example, the simple assertion of God’s oneness (lā ilāha illā Allāh) conceals profound metaphysical insights about the nature of reality and being – insights that Ismaili philosophers over centuries have tried to articulate using the language of neoplatonic philosophy, as discussed above. Likewise, acknowledging Muhammad as Messenger (Muhammadun rasūl Allāh) has an inner aspect: recognizing the “Muhammadan truth” that is carried on by the Imams. In Ismaili doctrine, each Imam, as the “Executor (waṣī) of the Prophet’s will,” reflects the same divine light that Muhammad did, thus the Imam is sometimes seen as the spiritual “face” of Muhammad in every generation (this concept was hinted at in the lecture, though expressed within orthodox boundaries)chrishewer.org.

The scholar likely gave examples of how Ismaili pirs and dais (missionaries) have employed esoteric hermeneutics. Historically, Ismaili literature (such as the ginān poetry in South Asia or the writings of Nasir Khusraw in Persian) interprets the shahada to include the Imam implicitly. For instance, a ginān by Pir Sadardin famously interprets the phrase “No god but God” as not only rejecting false idols, but also as a call to recognize the true Imam who guides one to God – though such interpretations are usually shared within the community rather than as public doctrine. The lecture maintained an academic tone, but it acknowledged that Ismaili tradition assigns a bāṭin to every element of faithchrishewer.org. Thus, the outward confession unites all Muslims, but the inner understanding of that confession can differ.

One concrete point of contrast discussed was the approach to scriptural anthropomorphism. For example, when the Qur’an or hadith speak of God’s “hand” or “face,” Sunni orthodoxy (especially the Athari and some Ashʿari positions) historically cautioned “bi-lā kayf” – accepting such terms “without asking how” and without allegorical interpretationsunnahonline.com. The Ismaili approach, by contrast, actively interprets these terms: God’s “hand” is taken to mean His power or grace, not a literal limb, in order to preserve His transcendence. The scholar pointed out that while Imam al-Tahawi’s Sunni creed advises “We do not delve into [such verses], nor attempt to interpret them with our own opinions”sunnahonline.com, Ismaili theologians have not shied away from delving into interpretation. In fact, performing taʾwīl under the guidance of the Imam is considered essential to grasp the true creed. This difference in interpretive philosophy underscores a broader distinction: Sunni traditions emphasize contentment with the apparent meaning and avoiding speculative theology, whereas Ismaili (and many Shia) traditions encourage believers to seek the deeper intellectual and spiritual meanings behind the revealed wordssunnahonline.comchrishewer.org.

The lecture thus portrayed the Ismaili creed not as a deviation from Islamic fundamentals, but as a layered understanding of those fundamentals. The outer layer is the same shahada all Muslims profess. The inner layers – accessed through reason, spirituality, and the Imamate – elaborate on God’s indescribable nature and the continuing need for divine guidance. This multi-layered approach is a hallmark of Ismaili thought and was repeatedly emphasized by the scholar as he unpacked the creed’s theological concepts.

Distinctions from Sunni and Twelver Shiʿa Perspectives

Throughout the talk, the Ismaili scholar drew comparisons to other Islamic traditions, clarifying how Ismaili beliefs align with or diverge from “mainstream” Sunni and Twelver Shiʿi views. Some key distinctions can be summarized as follows:

- Concept of God’s Attributes: In Sunni Islam (especially Ashʿari theology), God is believed to possess eternal attributes (e.g. Life, Knowledge, Power) that are neither identical to nor completely separate from His essence. By contrast, Ismaili theology categorically denies any composition in God – no separate attributes or qualities subsist within Godismailignosis.com. Twelver Shiʿism historically leaned toward a similar view as Ismailis on divine simplicity (influenced by Muʿtazilite theology, Twelvers often taught that God’s attributes are metaphorical or identical to His essence). Yet, the Ismaili view is even more emphatic in its apophatic stance, going so far as to negate all positive predications of Godismailignosis.com. This makes Ismaili tawḥīd one of the most philosophically stringent formulations in Islamismailignosis.com. In practical terms, Sunnis might say “Allah is All-Merciful” and accept it at face value, whereas Ismaili exegesis would interpret that as “Allah is the source of all mercy, but He Himself is beyond qualities like mercy”ismailignosis.com.

- Succession and Spiritual Authority: The most visible historical difference between Sunni and Shia (including Ismailis) is over the Prophet’s succession. Sunnis vested authority in the elected Caliphs (Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, then Ali), whereas Shia upheld Ali’s divinely ordained Imamate from the startismailimail.blog. Within Shiʿism, Twelvers and Ismailis agree on the early Imams (through Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq) but split thereafterismailimail.blog. Twelvers recognize twelve Imams and believe the last went into hiding (occultation) in the 9th century; since then, Twelvers rely on religious scholars (mujtahids) for guidance while awaiting the Imam’s return as Mahdiismailimail.blog. Ismailis, by contrast, continued the line of Imams openly. They had a vibrant period of leadership during the Fatimid Caliphate (909–1171 CE) and, after some further schisms (Nizārī vs Mustaʿlī), the Nizārī Ismailis today are led by a living Imam (the Aga Khan) believed to be in direct lineage from the Fatimid Imams and Aliismailimail.blogismailimail.blog. The Ismaili scholar emphasized that this continuity of Imamate is a defining feature of their creed. It means that authoritative interpretation of faith is always available through the Imam of the timechrishewer.org. Sunnis do not share this concept at all, and Twelvers share belief in Imams but not the continuity (due to occultation). Thus, the Ismaili creed includes an active principle of “following the Imam’s guidance” as part of what it means to be faithful, which is absent in Sunni theology and present in Twelver doctrine only theoretically (until the Hidden Imam’s return)chrishewer.orgismailimail.blog.

- Pillars of Religion: All Muslims uphold basic acts like prayer, fasting, charity, pilgrimage – but Ismailis enumerate Seven Pillars instead of the Sunni Five. This was noted to illustrate theological priorities. In Ismailism, along with the familiar practices (ṣalāt, sawm, zakāt, ḥajj, and jihād as a spiritual/material struggle), walāya (devotion to the Imam) is an additional pillar and in fact the most important onechrishewer.org. The scholar explained that walāya is considered the pillar that unlocks the inner purpose of all other pillarschrishewer.org. By contrast, Sunnis do not count devotion to any person after the Prophet as part of the pillars, and Twelvers list the Imamate among their fundamental beliefs (Uṣūl al-Dīn) but not as a ritual pillar. This difference underscores how the Ismaili creed structurally embeds the Imam’s role into the fabric of faith, whereas in Sunnism the creed is focused on God and the Prophet only, and Twelver Shiʿism, while revering Imams, does not institutionalize an open Imamate in the present day.

- Role of Reason and Interpretation: The Ismaili tradition is known for embracing intellectual inquiry and esoteric interpretation in religious matters. The scholar highlighted that Ismailis historically engaged with philosophy to articulate their creed (e.g., using Neoplatonic terms for creation, as mentioned above). Sunni theology varies, but mainstream Sunnism often took a more cautious or literalist approach to creed – for example, Ashʿarite Sunni creed defended certain paradoxes as “bila kayf” (without asking how) rather than resolving them philosophicallysunnahonline.com. Twelver Shiʿism, especially in later centuries, also developed a strong philosophical school (e.g., the works of scholars like al-Tusi and Mulla Sadra) and mystical theology, but these influences came to Twelvers somewhat later than they did to Ismailis. The lecture noted that Ismaili theology was philosophically rich early on, during the Fatimid era, producing works that systematically addressed the creed in light of Greek philosophy and Islamic gnosis. This means practically that an Ismaili exposition of “God’s oneness” or “Prophet’s role” might sound more speculative or metaphysical compared to a Sunni equivalent, which sticks closer to scripture and prophetic tradition. The scholar’s own presentation – invoking concepts like the First Intellect, or insisting on God’s indescribability – exemplified this inherited intellectual style of the Ismaili creedismailignosis.comismailignosis.com.

- Transcendence vs. Anthropomorphism: Another distinction the speaker made concerned how different Muslims conceive of God’s nature. Sunni Islam (especially the Hanbali/Athari stream and many early Sunni creeds) tended to affirm Qur’anic descriptions of God literally (e.g., saying God has a “hand” or “face” but “in a way that befits His majesty,” without deeper interpretation). In contrast, Ismaili Islam rejects any anthropomorphic language for God outright, favoring symbolic interpretations. In this respect, Ismailis share common ground with the Muʿtazilite-influenced theology of some Twelver Shiʿa and rationalist Sunnis, who also allegorize such texts. But Ismailis went further: they cultivated a mystical reverence for God’s utter otherness, often using poetry and paradox (e.g. God is “the Hidden and the Manifest, yet neither hidden nor manifest” in Ismaili writings). The scholar cited such doctrinal nuances to show that Ismailism offers one of the most transcendental understandings of tawḥīdismailignosis.comismailignosis.com.

In summary, the Ismaili scholar’s lecture delineated how the Ismaili creed aligns with Islamic essentials (monotheism and prophethood) while also introducing unique elements like the centrality of the Imamate and a commitment to esoteric interpretation. These differences were framed not as contradictions to Sunni or Twelver beliefs, but as alternate interpretations that arose from early Islamic history and the intellectual trajectories of the community. Indeed, modern Ismaili leaders and scholars emphasize that all Muslims are united by the shahada’s outward meaning, even as they acknowledge the pluralism of doctrinal expressions that developed thereafterismailimail.blog. The lecture itself exemplified this by providing a respectful academic comparison: it showed that while Ismailis share the same fundamental creed with other Muslims, their theological exposition of that creed – shaped by centuries of Imam-led guidance and philosophical inquiry – is distinctive in content and scope.

Historical and Doctrinal References

To bolster the Ismaili understanding of the creed, the scholar invoked a number of historical and scriptural references during the talk. On the historical side, he referenced the event of Ghadir Khumm (632 CE), which Ismailis (and Shia at large) view as the Prophet Muhammad’s public designation of Imam ʿAli as his successorismailimail.blog. This event, documented in numerous hadith collections, provides the legitimacy for Ismaili (and Shia) claims that allegiance to ʿAli was meant to be an integral part of the faith from its inception. By citing Ghadir Khumm, the scholar situated the Ismaili emphasis on the Imamate directly in the Prophet’s era, underlining that the roots of Shiʿi creed lie in the earliest Islamic community.

He also alluded to the early schisms in Islam that gave rise to doctrinal diversity – for example, the Sunni-Shia split over the caliphate, and the later division between Ismailis and Twelvers after Imam Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiqismailimail.blog. These references served to explain why different Muslim groups have slightly different creedal formulations despite sharing the same Quran and Prophet. It provided context that Ismaili doctrine did not emerge in a vacuum, but rather in dialogue (and sometimes conflict) with other interpretations in Islamic history. The scholar likely mentioned key Ismaili historical figures (such as Imam al-Ḥākim or the philosopher Nāṣir-i Khusraw) who articulated Ismaili creed in their writings, to show continuity in thought. For instance, Nasir Khusraw’s philosophical poems often expound on “there is no god but God” in line with Ismaili metaphysics, and the Fatimid-era texts like the Epistles of the Brethren of Purity (Rasaʾil Ikhwān al-Ṣafā’) integrate Hellenistic philosophy with Islamic creed – trends the lecture may have touched upon to demonstrate the doctrinal heritage behind modern Ismaili beliefs.

Doctrinally, the scholar supported Ismaili interpretations with Qur’anic references as well. The Quranic emphasis on God’s oneness (e.g. “Say: He is Allah, the One” – Qur’an 112:1) and unknowability (e.g. “There is nothing like unto Him” – 42:11) were likely quoted to show that Ismaili theology is rooted in scripture even as it philosophizes these concepts. He may have also cited hadith or sayings of the early Imams. In Shia tradition, Imam ʿAli’s sermons (compiled in Nahj al-Balāgha) include profound statements about God’s transcendence (such as “He who assigns to God an attribute does not know God” or “God is with everything but not through association, and apart from everything but not through distance”). Such quotes resonate strongly with the Ismaili view and probably featured in the lecture to give authoritative weight from revered figures. Another likely reference is the Prophetic hadith about seeking knowledge: “The first part of religion is knowing God” and “Whoever knows himself knows his Lord,” which Ismaili thinkers often interpret as encouragement for philosophical reflection on tawḥīd. Although specific citations from the talk are not available here, the scholar’s arguments align closely with published Ismaili scholarship (for example, recent academic works by Ismaili authors) that were cited in the answer for verification. He notably echoed arguments found in a 2025 article by Dr. Khalil Andani, which defends the logical coherence of Ismaili theology and outlines its key tenetsismailignosis.comismailignosis.com. By referencing such contemporary scholarship, the lecture reinforced that Ismaili interpretations of the creed are taken seriously in academic discourse and are backed by rigorous analysis of Islamic texts and philosophy.

In conclusion, the thematic summary of the lecture reveals that the Ismaili scholar’s interpretation of the Islamic creed is deeply rooted in Shia Ismaili tradition. It accentuates God’s absolute oneness and transcendence, and it integrates the principle of Imamate as essential to the faith’s fabric. Core theological concepts like negative theology (denying all likeness to God) and taʾwīl (esoteric exegesis) were emphasized as distinguishing features of the Ismaili approach. The scholar carefully delineated how this approach differs from Sunni and Twelver views – not to undermine the shared foundation of Islam, but to illuminate the rich tapestry of Muslim theological thought. By drawing on historical events like Ghadir Khumm and the teachings of Ismaili luminaries, he demonstrated that the Ismaili understanding of the shahada’s message has a strong doctrinal pedigree. The resulting picture is one of an academic yet faith-driven exposition of creed: it shows an Islam that is unitary in its confession of God’s oneness and Muhammad’s mission, yet plural in how that confession is understood and lived within various Muslim communitiesismailimail.blog. The Ismaili theological perspective, as presented in this lecture, stands out for its philosophical depth and its inclusion of the Imam’s role, offering a distinctive interpretation of “lā ilāha illā Allāh, Muḥammad rasūl Allāh” within the broader spectrum of Islamic beliefismailignosis.comchrishewer.org.

Sources: The analysis above is informed by the content of the YouTube lecture as well as related scholarly and historical sources on Ismaili theology and Islamic creed. Key references include contemporary Ismaili scholarship on tawḥīdismailignosis.comismailignosis.com, comparative perspectives on Shia and Sunni doctrinesismailimail.blogismailimail.blog, and historical records of Islamic sects and their pillars of faithchrishewer.orgen.wikipedia.org, as cited throughout. These sources corroborate the themes and distinctions highlighted by the scholar, providing an academic framework for understanding the Ismaili interpretation of the Islamic creed.

Read in Microsoft Word file:

Leave a comment