Written and collected by Zia H Shah MD

Sir Zafrulla Khan: Life, Achievements, and Scholarship

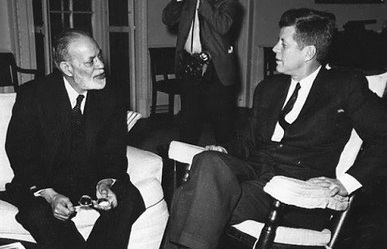

Sir Muhammad Zafrulla Khan (1893–1985) was a prominent Pakistani jurist, diplomat, and Islamic scholaralislam.org. He served as the first Foreign Minister of Pakistan after independence in 1947 and later represented Pakistan on the world stage, including terms as President of the U.N. General Assembly (1962–63) and President of the International Court of Justice (1970–73)alislam.org. A devout member of the Ahmadiyya Muslim community, Zafrulla Khan was renowned for his deep religious knowledge and scholarly works on Islamalislam.org. He authored several books in English and Urdu on Islamic topics, notably an English translation of the Qur’an (published 1970) and the biography Muhammad: Seal of the Prophets (first published 1980)britannica.comalislam.org. These contributions reflect his commitment to religious scholarship alongside an illustrious career in law and international diplomacy. Zafrulla Khan’s dual legacy as a statesman and a “distinguished scholar in world religions”alislam.org lends considerable weight to his writings on Islam. In particular, his biography of Prophet Muhammad serves not only as a historical account but also as a theological perspective, emphasizing the moral and spiritual principles exemplified by the Prophet’s life.

Islamic Doctrine of Defensive War: A Qur’anic Perspective

Islam’s stance on warfare as presented by Zafrulla Khan is unequivocal: war is permitted in Islam only in self-defense and to protect freedom of conscience, and even then it is tightly regulated by ethical constraints. The early Muslim community in Medina found itself under imminent threat from the Meccan leadership, which had vowed to annihilate them. Zafrulla Khan recounts that after Prophet Muhammad’s migration to Medina (622 CE), the Quraysh of Mecca “had declared war upon the Holy Prophet and the Muslims”, even issuing an ultimatum that unless the Prophet were expelled, they “would invade Medina in full strength and slaughter all the men…and enslave all the women”. In view of this genocidal threat, the Quranic revelation granted the Muslims permission to fight in self-defense: “the Muslims were accorded divine permission to take up arms in their defence and in the defence of their faith”. The Qur’an at this juncture pronounced: “Permission to fight is granted to those against whom war is made, because they have been wronged…They are those who have been driven out of their homes unjustly only because they affirmed: ‘Our Lord is Allah’…”. This inaugural verse of permission (Qur’an 22:39–40) makes clear that the justification for armed struggle was the wrong done to the Muslims by their oppressors – persecution and expulsion solely due to their faith. By mentioning that, if not for this divine sanction of defensive fighting, “cloisters and churches and synagogues and mosques” would be destroyed, the revelation situates the Muslim struggle as one to preserve religious freedom for all faiths.

Zafrulla Khan emphasizes that Islam regards war as an “abnormal and destructive” last resort, never as a desirable state. The Qur’an explicitly describes war as a conflagration or fire that God seeks to extinguish. In other words, when war becomes inevitable, it should be fought in a way that limits harm and hastens the return to peace. The sole legitimate objective of jihad (armed struggle) is to repel aggression and end persecution, not to conquer or convert. The Qur’an repeatedly stresses that “fighting is permissible only to repel or halt aggression”, and it commands: “Fight in the cause of Allah against those who fight against you, but do not transgress. Surely, Allah loves not the transgressors.”. This foundational rule from Qur’an 2:190 sets a firm limit: Muslims may fight only against those who initiate hostilities against them, and even then without transgression – meaning without brutality, injustice, or harm to non-combatants. All excess and atrocity is categorically forbidden. The Qur’an further ordains that if the enemy inclines to peace or ceases fighting, Muslims must also cease: “But if they desist, then surely Allah is Most Forgiving, Merciful… If they desist, then remember that no hostility is permitted except against the aggressors.”. In essence, once aggression stops, war must stop – there is no license for revenge or exploitation. The overarching aim is the elimination of fitna (persecution or oppression), which the Quran says is “worse than killing”. As Zafrulla Khan summarizes, any fighting forced upon the Muslims was to “put down aggression and persecution”, thereby restoring justice and freedom. This ethos is echoed by modern commentators: “The Quranic teachings about dealing with defensive war are black and white…highlighting the need to take every opportunity for peace”themuslimtimes.info. In the Islamic paradigm, peace is the default state – war is a constrained exception, only in defense against tyranny, to be conducted with proportionality and compassion.

Crucially, the Prophet Muhammad’s own conduct, as described by Zafrulla Khan, exemplified these principles. Muhammad is portrayed as “a man of peace” at heart whose enemies “would let him have no peace”, forcing him to take up arms “in defence of the most fundamental human right: freedom of conscience.”. He “hated war and conflict, but when war was forced upon him, he strove to render it humane”. The Prophet strictly forbade cruelty: no mutilation of enemies, no killing of non-combatants such as women, children, monks, or the elderly. He even stressed mercy toward captured foes – as seen after the Battle of Badr, where prisoners were treated kindly and many ransomed by teaching Muslim children to read instead of paying gold. All this was “designed towards making war humane and to put an end to the inhuman practices” prevalent in Arabia before Islam. Such restraint in victory underscores that the Prophet and his companions fought purely out of necessity, not for vengeance or domination. Indeed, the Qur’an lauds those warriors who, when they must fight, do so with justice: “whosoever transgresses against you, punish him in proportion to his transgression… and if you show patience, it is indeed best” (see Qur’an 16:126–127). In sum, Islamic scripture and the Prophet’s example – as expounded in Zafrulla Khan’s scholarship – firmly establish defensive war as a right and duty to confront aggression, never as a license for aggression.

Defensive War in Practice: Key Battles in Early Islam

Zafrulla Khan’s biography of the Prophet provides detailed historical context for the major military engagements of early Islam, demonstrating that each encounter was defensive in nature. The nascent Muslim community did not seek war with their opponents; rather, they were repeatedly forced into battle by the plots and attacks of the Meccan Quraysh and their allies. Below, we examine three pivotal conflicts – the battles of Badr, Uhud, and the Trench – to see how the principle of defensive war manifested in each case.

The Battle of Badr (624 CE)

The Battle of Badr, the first major armed conflict between the Muslims and the Quraysh, arose from escalating aggression by the Meccan leadership. By early 624, the Quraysh were sending armed caravans and tribal militias near Medina in order to intimidate the Muslim community and incite hostile desert tribes against them. These trade caravans doubled as military provocations, “accompanied by armed guards” and posing a direct threat to the security of Medina. Prophet Muhammad, as leader of the community, took steps to forestall attacks: he deployed small scouting parties to monitor Quraysh movements and intercept plots, and he sought to cut off the Quraysh caravan route as a pressure tactic. The biography explains that the Quraysh caravans “constituted a grave threat to the security of Medina”, so when news arrived of a particularly large caravan returning from Syria under Abu Sufyan’s leadership, the Prophet instructed his Companions to be ready to block its passage. This action was essentially a preemptive defensive measure – the Muslims aimed to diminish the Quraysh’s economic and military leverage, thereby deterring further attacks.

The Meccans, however, responded to the Muslims’ movements by escalating to open war. Upon learning that Muhammad’s forces might intercept the caravan, Abu Sufyan urgently dispatched a messenger to Mecca. According to Zafrulla Khan’s account, the emissary stirred up the Quraysh with dire warnings, shouting: “Men of Mecca, Muhammad and his Companions have set forth from Medina to attack your caravan!”. The Quraysh leaders seized this chance to mobilize a large punitive expedition. They “harangued them and incited them to get ready to go forth against the Muslims and to destroy them”. A Meccan army of around 1,000 fighters – vastly outnumbering the Muslims – was assembled with the avowed aim of annihilating Muhammad and his followers. Notably, even when Abu Sufyan’s caravan ultimately evaded the Muslims and passed safely beyond the “danger zone,” the Quraysh war party refused to abort its mission. Some voices in the Meccan camp suggested turning back at that point, but the militant chief Abu Jahl “rejected the suggestion violently and swore that they would proceed” to Badr regardless, to teach the Muslims a final lesson. His faction intended to make a public show of force at Badr – celebrating a victory even before it was won – “so that their prestige may be established throughout the country”. This detail illustrates that the Meccans were the clear aggressors seeking battle; they marched on Badr even though the immediate cause (the caravan) had vanished, driven by hubris and hatred for the new faith.

Thus, the encounter at Badr was essentially forced upon the Muslim community. Muhammad had not initially set out to engage the Quraysh army; he only learned of the approaching Meccan force en route and then consulted his companions on how to respond. Both the Emigrants from Mecca and the Ansar (Medinan helpers) agreed to stand and fight in defense of their faith and city. The resulting battle on the plain of Badr (17 Ramadan 2 A.H.) was a defensive showdown in which 313 ill-equipped Muslims, through what they believed was divine aid, won a stunning victory over the superior Meccan force. Zafrulla Khan notes that this triumph, though miraculous in Muslim eyes, was fundamentally about survival – it “changed the whole course of human history” by proving that a persecuted community could prevail against tyranny. In the aftermath, the Muslims demonstrated remarkable restraint and mercy, as highlighted earlier: enemy captives were treated with kindness, and those who could educate were allowed to ransom themselves by teaching, rather than with money. The Battle of Badr thus epitomized the Quranic principle: “no hostility is permitted except against the aggressors”. The Muslims fought only to repel the aggressors, and once those aggressors were subdued, no further bloodshed was pursued. Badr set the precedent that Islam’s wars would be fought defensively, with faith that God’s help accompanies the oppressed, as indeed the Qur’an later reminded the believers: “Allah had already helped you at Badr when you were few in number” (Qur’an 3:123).

The Battle of Uhud (625 CE)

In the year following Badr, the defeated Quraysh of Mecca prepared a second onslaught to take revenge and eliminate the Muslim community. The Battle of Uhud (March 625) confirms the defensive nature of the Muslims’ posture, as it was the Quraysh who initiated hostilities once again. Embarrassed by their loss at Badr, the Quraysh spent months rallying allies and resources for a retaliatory campaign. Zafrulla Khan describes how the Quraysh leadership openly declared their violent intentions: they reproached each other after Badr for having “neither killed Muhammad, nor enslaved the Muslim women, nor plundered their homes”, and thus having “missed a great opportunity”. Now determined to correct that “mistake,” they amassed a force of about 3,000 fighters and advanced towards Medina the next year, intent on achieving what they saw as unfinished business. The stated goal of the Meccan chiefs was, unmistakably, to murder the Prophet, massacre his followers, and sack the city. Some among the Quraysh argued in council that they should be satisfied with their prestige restored (after one victory at Uhud) and avoid overextending into Medina, but the more bloodthirsty voices prevailed. The Meccan army marched northward to Medina, seeking a decisive confrontation.

Prophet Muhammad, learning of the approaching invasion, consulted with his companions about how best to defend Medina. Initially, he inclined to fortify the city and fight from within Medina’s defenses, a tactically sound plan for a vastly outnumbered group on home ground. A number of younger companions, however, urged to meet the enemy outside in open battle, and the Prophet eventually acceded to this wish. Thus, the Muslims went out to face the Quraysh at the foothill of Mount Uhud, just outside Medina. Importantly, the Muslim army at Uhud consisted largely of the same volunteers who had fought at Badr, underscoring continuity in their defensive purpose. They were fighting to protect their community, not to invade or expand territory.

The Battle of Uhud itself was hard-fought and ended in a setback for the Muslims. After some early success, a mistake by a contingent of archers (who left their assigned post contrary to the Prophet’s orders) allowed the Quraysh cavalry to flank the Muslim rear, turning the tide of battle. Many Muslims were killed and the Prophet himself was wounded. Yet even in this moment of victory, the Meccans did not achieve their core aim: they neither captured Medina nor destroyed the Muslim community. Notably, the Quraysh did not press on to attack Medina directly after the battle. According to Zafrulla Khan’s account, as the defeated Muslims regrouped, the Quraysh army debated whether to capitalize on the win by marching into Medina. Some leaders insisted they should “go back [to Medina], attack and destroy the Muslims” completely, while others cautioned that the Muslims would fight desperately if cornered and that the Meccan forces were in no condition to lay siege. Ultimately, the more cautious approach won out: the Quraysh, content with having avenged Badr, decided to withdraw to Mecca rather than risk an urban battle. This decision was also influenced by a clever show of resolve by the Muslims. The very next morning after Uhud, the Prophet Muhammad rallied his injured companions and marched out a few miles from Medina, to show the enemy that the Muslims were still strong and ready to fight again if pursued. This bold move – coming from a community protecting its very existence – apparently convinced Abu Sufyan and the Quraysh to abandon any plan of attacking Medina itself. They returned home, leaving the Muslims bruised but unbroken.

From an Islamic perspective, the outcome of Uhud was a test of perseverance rather than a decisive defeat. The Qur’an revealed after Uhud reminded the believers that such days of triumph and setback alternate in order to distinguish the steadfast (Qur’an 3:139–142). Zafrulla Khan notes that the Muslim loss at Uhud, while painful, “inflicted no great permanent loss”. The community quickly regrouped and learned a vital lesson in discipline and unity, resolving to obey the Prophet’s commands unwaveringly in the future. Strategically, the battle underscored that the Muslims’ survival was still precarious; they had to remain vigilant against future onslaughts. But crucially, the moral high ground remained with the Muslims: they had fought only to defend their city from an aggressor. Even in victory, the Meccans failed to follow through on their threats to enslave and slaughter, which indicates that the Muslims’ spirited defense at Uhud succeeded in deterring the worst of the aggression. The pattern of events – Mecca raising an army to crush Medina, Medina fighting back to protect itself, Mecca retreating without achieving annihilation – reaffirms that the Muslims engaged in war purely reactively, for survival. As the Qur’an summarizes, the Meccans were the ones who “were the first to commence hostilities” (Qur’an 9:13), whereas the Muslims’ duty was to endure with patience and remain ready to repel those hostilities when they came.

The Battle of the Trench (627 CE)

Two years after Uhud, the Quraysh made one more concerted attempt to eliminate the Muslim community – an event known as the Battle of the Trench or the Siege of Medina (early 627 CE). This episode most clearly illustrates the concept of purely defensive war, as the Muslims adopted an entirely defensive strategy and fought a campaign of fortification and attrition to protect their city. Zafrulla Khan sets the scene by noting that by the fifth year after the Hijra, “the bitter hostility of Quraish towards Islam and the Muslims had assumed dangerous proportions.” The Meccans spread “poisonous propaganda” among the desert tribes, rallying many of them into an anti-Muslim coalition. Several of the Prophet’s bitter enemies who had fled Medina (notably members of the Jewish tribe of Banu Nadir, exiled earlier for treason) also joined this grand alliance【26†L100-108】【26†L109-117】. In the winter of 627, a confederate army of at least 10,000 (Quraysh and their tribal allies) marched on Medina from all sides, determined to besiege the city and overwhelm the Muslims once and for all. Facing this enormous threat, Prophet Muhammad convened his followers to devise a defensive plan. A companion, Salman al-Farsi, suggested an innovative tactic unfamiliar in Arabia: digging a trench around the vulnerable perimeter of Medina to block the enemy’s cavalry. The Prophet approved this plan, and the Muslims — only a few thousand in number — labored swiftly to excavate a wide ditch across the northwestern approaches to the city. Zafrulla Khan describes how Muhammad personally supervised the digging and shared in the hardship of the labor, illustrating his leadership by example. Despite cold weather and scant resources, the community’s solidarity paid off: “by the labour of the entire body of Muslims, the trench was completed” just in time as the coalition forces drew near.

When the Meccan-led confederates arrived and confronted this unexpected obstacle, their offensive momentum was blunted. Accustomed to traditional open-field battles, the allied forces found themselves confounded by Medina’s new defenses: “They were brought to a stand by the trench…a barrier which they could not pass. They were astonished and disconcerted at the new tactics of the Holy Prophet.”. Unable to charge directly into the city, the enemy camped on the far side of the trench, and a prolonged siege ensued. The Muslims, though vastly outnumbered, maintained their defensive lines along the trench and the city’s other flanks. The coalition forces made numerous attempts to breach the ditch or find a weak point. At times, small groups of enemy warriors managed to vault the trench in narrow sections, leading to brief skirmishes. But these penetrations were contained by Muslim defenders at great effort, and none resulted in a general breakthrough. As Zafrulla Khan notes, all the coalition’s efforts “were without effect. The trench was never crossed in force”, and the invaders grew frustrated as the siege dragged on.

Inside Medina, conditions were dire for the Muslims. They endured weeks of fear, hunger, and exposure while manning the defenses continuously. The biography vividly records that during the height of the siege the Muslims were “half-famished” and exhausted, to the point that by the end “they were absolutely spent and helpless”. Morale was tested not only by the external threat but also by a grave internal treachery: midway through the siege, the Jewish tribe of Banu Qurayza, which controlled a section of Medina’s inner defenses, betrayed the Muslims and conspired to aid the attacking forces from within. This created a nightmare scenario – the Muslims were caught between a massive enemy outside and perfidy inside, “between the upper and nether millstone,” as Zafrulla Khan puts it. Despite these severe challenges, the Muslims did not surrender or resort to desperate measures; they held the line with remarkable tenacity, inspired by their faith that God would deliver them. The Qur’an (Surah 33) later praised the believers’ steadfastness under these extreme conditions (Qur’an 33:9–20) and indeed describes how divine aid turned the tide. After roughly three weeks of stalemate, the coalition’s will began to erode. Medina’s defenders had prevented any significant incursion, and the confederates started running low on supplies and morale in the harsh winter weather. In the end, a sudden storm and deep distrust between the various pagan tribes caused the coalition to disband and retreat abruptly. Zafrulla Khan notes that the siege was finally lifted – the invaders departed Medina in frustration without achieving any of their objectives. The Muslims, by God’s grace, had prevailed by pure defense, with minimal casualties on either side. This outcome is exactly in line with the Quranic promise that “Allah repelled the disbelievers in their wrath; they gained no advantage” (Qur’an 33:25).

The Battle of the Trench stands as a definitive example that the Prophet Muhammad sought no worldly conquest. Faced with annihilation, he chose to entrench rather than attack. There was no battle of maneuver or quest for glory – only a patient defensive posture that forced the enemy to give up. When the siege ended, the Muslims immediately turned to neutralize the treachery of Banu Qurayza (through a separate, subsequent operation), but notably, they did not pursue the retreating coalition with vengeful counter-attacks. The Quraysh and their allies were allowed to withdraw to Mecca unharmed. In fact, the Prophet is reported to have said after this victory, “Henceforth, we will go to them; they will not come to us”, indicating that the Quraysh’s days of attacking Medina were over. Indeed, the failure of the siege was the last major offensive the Meccans ever launched. It paved the way for the Treaty of Hudaibiya (628) and eventually the peaceful conquest of Mecca (630) by the Muslims with hardly any fighting. The collapse of the Confederate siege confirmed that aggression against the Muslims had finally been thwarted and that Islam’s spread in Arabia would proceed with far less bloodshed going forward. Zafrulla Khan’s narrative underscores that throughout all these campaigns, Prophet Muhammad consistently acted on Quranic defensive principles: he never initiated hostilities against any tribe without invitation to peace, he only fought those who attacked first or committed treason, and whenever possible he chose strategies (like the trench) that minimized casualties on both sides. As the Qur’an says, “If they incline towards peace, then incline to it [also]” (Qur’an 8:61) – a guideline the Prophet scrupulously observed.

Conclusion

In light of Sir Zafrulla Khan’s biography Muhammad: Seal of the Prophets and the Qur’anic verses therein, it is evident that defensive war is not only permitted in Islam but is portrayed as a moral imperative in the face of injustice. The life of Prophet Muhammad, as analyzed by Zafrulla Khan, powerfully illustrates that the early Muslims took up arms only under relentless persecution and direct attack. They fought “in defence of the most fundamental human right: freedom of conscience” – to protect their lives, their faith, and the innocent from tyranny. At no point did Muhammad seek war for its own sake or for worldly gain; indeed, he “hated war and conflict”, and every engagement was “forced upon him” by enemy aggression. Even so, when compelled to fight, he exemplified the highest ethics of war: mercy, restraint, and swift cessation of hostilities once the threat abated. This aligns exactly with the Qur’an’s injunctions that fighting is allowed only against those who initiate war, that Muslims must not transgress limits of justice and compassion, and that peace is always preferable when attainable. The key battles of Badr, Uhud, and the Trench all validate that Islamic military action under the Prophet’s leadership was defensive in nature – responses to aggression rather than acts of aggression. As one contemporary analysis succinctly puts it, the Quranic guidance on war “highlights [the] need to take every opportunity for peace” and frames even necessary combat as a means to end oppression, not to perpetuate violencethemuslimtimes.info.

Sir Zafrulla Khan’s work, supported by the Qur’an and historical evidence, thus serves as a compelling defence of defensive war in Islam. It refutes misconceptions of Jihad as an instrument of holy war for expansion, showing instead that Prophet Muhammad was a peace-maker forced into battle, who fought with reluctance and invariably in self-defense. Islam’s earliest wars established a paradigm: religious persecution and aggression must be resisted, but with moral rectitude and with peace as the ultimate goal. This legacy, preserved in Islamic scripture and exemplified by the Prophet, remains a guiding principle in Islamic thought – that justice must be defended, but “Allah does not love aggressors.” (Qur’an 2:190).

Sources: Sir Muhammad Zafrulla Khan, Muhammad: Seal of the Prophets; Zia H. Shah, “Defensive War in the Holy Quran in 600 Words” themuslimtimes.info themuslimtimes.info; The Holy Qur’an (translations as cited above).

Leave a comment