Presented by Zia H Shah MD

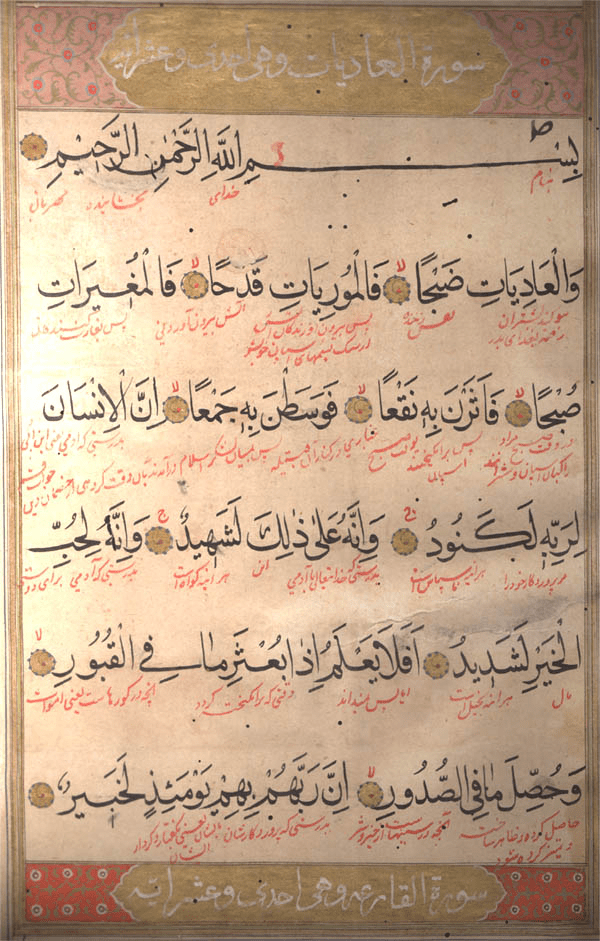

Introduction: Surah Al-ʿĀdiyāt (Arabic: العاديات) is the 100th chapter of the Qur’an, consisting of 11 short verses revealed in powerful, rhythmic Arabic. According to most sources it is a Meccan surah (from the early period of Muhammad’s prophethood), though some scholars – including companions like Ibn ʿAbbās and Imam Mālik – believed it was revealed later in Madinahislamicstudies.info. The chapter opens with a series of oath-like verses evoking a vivid scene of war horses charging at dawn, panting and striking sparks with their hooves, and concludes with a stark reminder of human ingratitude and the impending Day of Judgment. In fact, one classical summary states that Al-ʿĀdiyāt “gives an example that horses are more grateful to their owners than men are to their Lord (Rabb)”en.wikipedia.org. This surah’s dramatic imagery and moral themes have inspired extensive commentary in Islamic tradition, as seen in an 18th-century Qur’an manuscript of Al-ʿĀdiyāt in elegant naskh script with a Persian translation in red margins.

Scientific Commentary (Historical & Linguistic Insights)

Revelation Context and Imagery: The name Al-ʿĀdiyāt can be translated as “The Galloping Chargers” or “The Racers.” The surah begins by swearing “by the ˹steeds˺ that run, with panting (sound)” (Arabic: wal-ʿādiyāti ḍabḥā)al-islam.org. This oath conjures the image of battle horses at full gallop, breathing hard. Some early Muslims thought these verses referred to the horses used by the Muslim fighters at the Battle of Badr (2 AH); however, Imam ʿAlī is reported to have rejected that, noting there were only two horses at Badral-islam.org. Instead, ʿAlī (and others) suggested the oaths could refer to swift camels of the Hajj pilgrimage running between the holy sites of ʿArafāt, Muzdalifah, and Mināal-islam.org. This alternate view highlights how the Arabic terminology is rich enough to envision both war chargers and pilgrimage camels – in either case symbolizing noble exertion. (Indeed, some commentators ultimately include both meanings under al-ʿādiyāt, emphasizing that the wording should not be limited to a single scenarioal-islam.org.)

Linguistic Features: The Qur’anic Arabic in this surah is concise yet evocative. The term al-ʿādiyāt comes from a root meaning “to run swiftly or charge,” and classical lexicons note it implies racing with great speedal-islam.org. The word ḍabḥ in verse 1 refers to the sound of heavy panting – the heaving breath of an animal running at full tiltal-islam.org. Such an image is grounded in real physiology: a horse galloping will breathe deeply and rapidly (almost one breath per stride) to intake enough oxygen, a phenomenon observable and “heard” as panting. Verse 2 continues: fal-mūriyāti qadhaḥā – “by those that strike sparks of fire.” The phrase mūriyāt is derived from īrā’, “to kindle a fire,” and qadhaḥ means striking or ignitingal-islam.org. This describes how the fast horses’ hooves hit rocks and flints, producing visible sparks in the dark of early morningal-islam.org. Modern science affirms the literal possibility: friction can cause heat and small sparks when iron or steel (horseshoes or horses’ metal armor) strikes stone. The Qur’anic depiction is thus not fanciful – desert riders did witness flashes of light from horses’ hooves on rocky terrain at nightal-islam.org. Verse 3 swears by “the chargers at dawn” (al-mughīrāti ṣubḥā), using mughīrāt from ighārah, “to raid or attack suddenly.” Historically, Arab warriors preferred to begin their raids at daybreak – they would stealthily approach by night and strike at first light, a tactic seen as courageous (since attacking in daylight, as opposed to the cover of full darkness, demonstrated boldness)islamicstudies.infoal-islam.org. The surah’s imagery aligns with that custom, as the charging horses “raise clouds of dust” in the morning air (verse 4) and then plunge “into the midst of the enemy ranks” (verse 5) without hesitational-islam.org. Each term underscores speed, surprise, and intensity: atharna bi-hī naqʿā indicates kicking up dust so thick it hangs like a cloudal-islam.org, and fawa-saṭna bi-hī jamʿā portrays the war mounts penetrating the enemy gathering head-onal-islam.org.

Natural Phenomena and Realism: The Qur’an’s oath by these phenomena suggests their significance. From an environmental perspective, the mention of dust clouds (naqʿ) highlights the dry desert setting – in the still air of dawn, a stampede of hooves would indeed send up plumes of dust, whereas later in the day wind or heat might dissipate such clouds more quicklyislamicstudies.info. The scene evokes a synchronized cavalry charge with a sensory richness: thundering hooves, snorting breaths, striking sparks in the twilight, and swirling dust in the morning sun. Modern readers can find parallels in, say, the way off-road vehicles or cavalry units kick up dust storms in arid terrain, or how fire sparkles under a horse’s shoes on rocky ground – timeless physical details connecting ancient warfare to observable reality. Such fidelity to natural details has been noted by commentators as a mark of the Qur’an’s eloquence: it captures the drama of battle in a few words that are both poetically powerful and empirically accurate. Even the feminine plural forms used for the charging animals in Arabic (indicating groups of mares) reflect classical Arab preferences – they prized war mares for its loyalty and endurancelolliesplace.wordpress.comal-islam.org. In sum, the surah’s language merges linguistic precision with vivid observation of nature and human behavior, setting the stage for the moral lesson that follows.

Philosophical Commentary (Ethical and Existential Themes)

After painting this breathtaking scene, the surah abruptly shifts in verse 6 to the human condition: “Indeed, mankind is ungrateful to his Lord.” This statement (“innal-insāna li-rabbihī lakanūd”) packs an ethical judgment that invites deep philosophical reflection. It speaks to human nature, moral responsibility, and the tendency toward ingratitude. Below, we analyze key themes:

- Human Ingratitude vs. Gratitude: The Arabic word kanūd (translated as “ungrateful” or “extremely ungrateful”) is rich in nuance. Classical scholars like Hasan al-Baṣrī explained al-kanūd as a person who counts their misfortunes but forgets the blessings Allah has givenislamicstudies.info. In other words, the kanūd personality dwells on negative events and fails to acknowledge positive gifts – a psychological trait still recognizable today. Another early scholar said kanūd is one who uses God’s bounties for sinful purposes, while yet another defined it as one who focuses on the gift rather than the Giverislamicstudies.info. All these interpretations point to a moral failing of ingratitude and misaligned priorities. Ethically, the surah is prompting readers to examine their own attitudes: do we, as humans, remember our benefactor (the Creator) with thankfulness, or do we selfishly take the good and complain about the bad? The war horses in the oaths implicitly contrast with humankind – the horses exhibit loyalty and gratitude to their human masters (charging into danger at their command) despite receiving only fodder in returnislamicstudies.infoislamicstudies.info. Humans, by contrast, enjoy countless blessings from their Lord – life itself, intellect, sustenance – yet many “do not recognize or acknowledge” these divine favorsislamicstudies.info. This comparison raises a philosophical question about ingratitude as a moral failing: Why would a rational human, uniquely endowed with intellect and conscience, be less grateful than a beast trained with a few oats? The surah challenges the reader to overcome this base tendency. In a sense, it affirms a view found in many wisdom traditions that gratitude is a fundamental virtue and that forgetting one’s benefactor (whether one’s parents, society, or God) is a sign of ethical decay.

- Love of Wealth and Materialism: Verse 8 continues the critique: “And he is surely intense in love of ḫayr (good things).” Here al-ḫayr (“the good”) is understood by the commentators to mean wealth or worldly richesislamicstudies.info. The Qur’an is observing that humans have a passionate love of material good. Philosophically, this touches on the classic debate about materialism and the proper role of wealth in a good life. The text does not deny the utility of wealth – indeed, Islamic teachings permit and even encourage earning one’s livelihood and using wealth for good – but it condemns an excessive, obsessive love of wealth that eclipses higher valuesislamicstudies.infoislamicstudies.info. One commentary illustrates this with a vivid analogy: Wealth should be to the human heart as water to a ship. Water beneath a ship allows it to sail, but if water fills the ship, it sinks itislamicstudies.info. In the same way, wealth used as a tool or support – kept “under” control – is beneficial, but once love of wealth enters one’s heart, it can sink one’s moral and spiritual lifeislamicstudies.info. The surah’s wording “violent in the love of wealth” suggests that uncontrolled greed can drive people to immoral extremes. Ethically, this is a warning similar to that found in other traditions – for example, the New Testament’s remark that “people will be lovers of themselves, lovers of money, … ungrateful, unholy” in perilous timesbiblestudytools.com. Both the Qur’anic and Biblical perspectives recognize unrestrained avarice as inimical to righteousness. The philosophy of contentment emerges here: wealth in itself is neither evil nor good, but the attachment of the heart to wealth is dangerous. A sound approach, the commentators note, is to treat wealth like any necessity – to be acquired and used without letting it dominate one’s affectionsislamicstudies.infoislamicstudies.info. The surah thereby challenges readers to reflect on their motivations: Do we love “the good things” as ends in themselves, or do we value higher ethical and spiritual goods above mere accumulation?

- Self-Awareness and Conscience: Verse 7 of Al-ʿĀdiyāt contains a subtle phrase: “And indeed, he (mankind) is to that a witness.” This can be understood in two ways. Some Qur’anic exegetes interpret it to mean God is witness to human ingratitudequran.com. Others, however, take the pronoun as referring to insān (the human being) – meaning the human is a witness against himself in this regardquran.com. The latter interpretation has profound philosophical implications about human conscience and self-knowledge. It suggests that deep down, a person knows when they are ungrateful or covetous; the evidence is in their own soul, if they only reflect. Even if we hide our shortcomings outwardly, our inner self bears testimony. This aligns with the idea that humans have an innate moral compass (fitra in Islamic thought) – when we act against it (such as showing ingratitude toward our Creator), we experience an inner witness or guilt. The surah thereby invites an attitude of moral introspection. Instead of dismissing the charge of ingratitude, one is prompted to ask: “Am I myself aware of this tendency? In my candid moments, do I admit that I haven’t thanked God as I should?” Such self-questioning is the beginning of ethical reform. In a broader existential sense, the verses underscore how human beings are caught between two poles: they can be loyal, brave, and grateful (like the charging horses), or cowardly, greedy, and thankless. The Qur’an elsewhere notes this dual potential: humans can reach the “highest of the high” or fall to the “lowest of the low.”al-islam.orgal-islam.org The commentary of Al-ʿĀdiyāt echoes this view, explaining that mankind is not irredeemably evil by nature, but rather capable of great good or great evil depending on whether they follow divine guidanceal-islam.orgal-islam.org. This understanding harmonizes the apparently pessimistic tone of verses 6-8 with the Quranic optimism about human honor (as in Qur’an 17:70 which says “We have honored the children of Adam…”al-islam.org). In summary, Al-ʿĀdiyāt philosophically urges us to recognize our lower tendencies (ingratitude, greed) so that we can transcend them and live up to our higher nature through gratitude, generosity, and mindfulness of divine accountability.

- Motivation for Action – Between World and Hereafter: Implicit in the surah is the question of what drives human action. The imagery of the war horse suggests single-minded devotion to duty – the horse rushes forward, undeterred by danger, because it heeds its master’s call. Humans, on the other hand, often rush through life driven by love of wealth or worldly gain (as verse 8 indicates). The juxtaposition asks: what “master” are we truly serving? Are we as devoted to our Lord as the battle-steed is to its rider? This resonates with a philosophical theme of right motivation: noble actions are those done with the right intention (such as seeking to please God or uphold justice), whereas ignoble actions stem from base intentions (greed, ego, ingratitude). By reminding the listener of the impending Day when all secrets are revealed, the surah implicitly encourages aligning one’s motivations with a higher purpose beyond material temporality – an idea comparable to exhortations in other traditions to remember the impermanence of life and the reality of death as a way to live more authentically (akin to Stoic and Christian memento mori concepts).

In all, the philosophical commentary on Surah Al-ʿĀdiyāt reveals it to be a meditation on human nature: our capacity for loyalty and bravery versus our tendency to selfishness and thanklessness. It offers a moral diagnosis (man tends to ingratitude and excessive material love) but also, by contrast with the faithful steeds and by reference to the Day of Judgment, a cure: to cultivate gratitude, temper our attachment to wealth, and stay conscious of our ultimate accountability.

Theological Commentary (Classical Exegesis and Comparative Theology)

Insights from Classical Islamic Exegesis: Muslim scholars through the centuries have studied Al-ʿĀdiyāt extensively, unpacking its linguistic subtleties and theological messages. Major commentators like Ibn Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī, Ibn Kathīr, and al-Qurṭubī have all addressed this surah in their tafsīr works. They generally agree on the overall meaning while offering nuanced interpretations of certain phrases:

- Oaths of Verses 1–5: Exegetes discuss what objects or events Allah is swearing by in the opening oaths. The majority, as noted, view it as an oath by war horses engaged in jihād (striving in God’s cause)al-islam.org. They describe the scene as allegorical emphasis: God swears by these noble animals and their arduous deeds to underline the truth of the following statement (that man is ungrateful)islamicstudies.info. Some early authorities, however, extended the reference to include the swift Hajj camels, as mentioned before, based on reports from Companions like Ibn ʿAbbās and ʿAlīal-islam.org. Al-Qurṭubī in his tafsīr reconciles that the term al-ʿādiyāt could be general enough to encompass any beings that ardently rush forward – the context (raiding at dawn, raising dust) strongly suggests horses in battle, but the broader lesson (devotion in action) is not lost even if one considers the pilgrimage contextal-islam.org. In any case, the hard tasks of the chargers are invoked as a testimony against human ingratitudeislamicstudies.info. This rhetorical style – oaths by striking images of nature or history – is common in the Qur’an and is meant to grab attention and establish a point of reflection for the audience.

- “Kanūd” (Ungrateful): Classical commentators often elaborate on kanūd by quoting early Islamic authorities. Ibn Kathīr cites Ibn ʿAbbās, Mujāhid, Qatāda and others all explaining kanūd as “ungrateful”, particularly ungrateful for God’s favorsquran.com. Al-Ḥasan al-Baṣrī’s definition (as one who tallies hardships and forgets blessings) is frequently mentionedquran.com, indicating a deep understanding of human psychology in the Qur’anic milieu. This definition is found in al-Qurṭubī’s commentary as well, who notes that kanūd signifies someone exceedingly negative and thankless despite bounty. The theological significance is that ingratitude (kufr al-niʿma) is seen almost on par with impiety – in fact, the word kufr itself in Arabic can mean ungrateful, and rejecting faith is often described as ingratitude toward God. Thus, the commentators warn that kanūd in this verse characterizes the typical disbeliever, but it could also apply to anyone who neglects to thank God properlyislamicstudies.infoislamicstudies.info. Some scholars, according to Ma’āriful Qur’ān tafsīr, even restricted the meaning of “insān” (man) in verse 6 to the unbelievers specifically, since true believers are taught to be gratefulislamicstudies.info. However, they hasten to add that if a Muslim exhibits these qualities (ingratitude and greedy love of wealth), he or she should be very concerned – as it is characteristic of those who lack sincere faithislamicstudies.info. Thus, the theological consensus is that these verses serve as a mirror: most humans have these flaws, but the righteous are those who strive to avoid them.

- “He is surely a witness over that” (verse 7): As mentioned, exegetes differ whether the pronoun refers to God or man. Al-Ṭabarī reports both views: one, “Allah is indeed witness to man’s ingrained ingratitude,” and two, “Man is himself fully aware (deep down) of his own ingratitude.”quran.com Interestingly, both readings convey truth in Islamic theology. God’s omniscience means no ingratitude or secret is hidden from Him (as the last verse also emphasizes), and the Day of Judgment will confirm that. At the same time, the Quranic view of the self (nafs) is that humans have been given an inner faculty (the soul or conscience) that testifies to good and evil (cf. Qur’an 91:7-8) – so a person really “knows” when he has been ungrateful or sinful, even if he covers it up externally. Al-Rāzī and others often like to explore such dual layers of meaning, seeing no contradiction in both being intended. Thus the verse is rich: it reminds us that God is a witness to our deeds, and also that our own souls bear witness (leaving us no excuse but to repent and reform).

- Love of Wealth (verse 8): Many classical tafsīrs note that al-khayr (“the good”) is used idiomatically for wealthislamicstudies.info. They often reference other Qur’anic verses like 2:180, where khayr clearly means material goodsislamicstudies.info. The commentators expound that the “intense love” of wealth is blameworthy when it leads to hoarding, stinginess, and distraction from God. However, they clarify an important point: Islam does not advocate poverty or renunciation of all worldly goods; rather, it condemns excessive attachment to wealth. As the commentary of Ma’āriful Qur’ān puts it, acquiring and saving wealth to meet one’s needs is permissible (even obligatory to a degree), “but having its love in the heart is bad.”islamicstudies.info They use practical examples: one relieves oneself or takes medicine out of necessity, but one does not love the act of doing soislamicstudies.info. Likewise, a believer may earn and use wealth as needed, yet his heart should remain detached – loving God and righteousness more than money. Rūmī, the famous Sufi poet, was quoted by some later commentators with the ship and water analogy we mentionedislamicstudies.info. In theological terms, wealth is a test (fitna), and the surah implies most people fail that test by falling in love with the worldly “good” instead of using it as a tool to attain the real Good (God’s pleasure).

- The Day of Judgment (verses 9–11): The final verses bring a dramatic eschatological scene: “Do they not know that when what is in the graves is scattered about, and what is in the breasts is made known – surely their Lord, on that Day, is fully aware of them?” Early authorities like Ibn ʿAbbās explained “buʿthira mā fī l-qubūr” as meaning the dead will be removed from their graves (resurrection)quran.com. This is entirely in line with Islamic doctrine that all the dead will be raised up on Yawm al-Qiyāmah (the Day of Resurrection). The phrasing “poured out” or “scattered” from the graves evokes an image of graves turning inside out – no corpse remains hidden. Likewise, “ḥuṣṣila mā fī ṣ-ṣudūr” was glossed by Ibn ʿAbbās as “that which was in their souls/hearts will be brought forth and made apparent”quran.com. Al-Qurṭubī notes that this making known of what’s in the breasts means distinguishing the good and evil hidden insidequran.com. All inner intentions, secrets, and feelings that people harbored will be exposed by God’s knowledge. Some classical scholars pointed out variant readings of the verb (e.g. ḥuṣila with a different vocalization meaning “brought to light”) but the essence is the samequran.com. Theological discussions here emphasize God’s perfect knowledge and justice: not only will outward deeds be judged, but the inner reality behind those deeds will be laid bare. The last verse (“Verily, their Lord is, on that Day, fully aware of them (and all they did)”) is taken as an assurance that no deed, good or bad, is overlookedquran.com. Ibn Kathīr writes, “He knows all of what they used to do, and He will recompense them with the fairest recompense. He does not wrong even the weight of an atom.”quran.com In other words, divine justice will be exact and omniscient. This serves as both a warning to the ungrateful and a comfort to the righteous: hidden sins will be punished, but hidden virtues and wrongs suffered patiently will also be rewarded. Classical exegetes often link such verses to broader Islamic eschatology – the blowing of the trumpet, the gathering of mankind, the giving of the records of deeds, etc. While Al-ʿĀdiyāt is very brief, it effectively compresses the end-time theology: resurrection from graves, revelation of secrets, and God’s complete awareness leading to judgment.

Comparative Theology – Parallels in the Bible and Torah: The themes in Surah Al-ʿĀdiyāt find resonance in earlier scriptures, illustrating a common moral and theological core in the Abrahamic traditions:

- Divine Judgment and Resurrection: The idea that the dead will be raised and judged by God is a cornerstone in Christian and Jewish eschatology as well. For instance, the Book of Daniel (considered part of the Hebrew Bible/Ketuvim) states: “Many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life, and some to shame and everlasting contempt.”leaderu.com This is a clear parallel to “what is in the graves is brought out” in Al-ʿĀdiyāt. The New Testament echoes the same truth; Hebrews 9:27 reminds that “it is appointed unto men once to die, but after this the judgment,” and in a vision of Judgment Day, John says, “I saw the dead, great and small, standing before the throne… and the dead were judged… according to their works.” (Revelation 20:12)leaderu.com. The Qur’anic depiction of God’s thorough awareness (“fully Acquainted”) also parallels verses like Psalm 44:21: “Would not God find this out? For He knows the secrets of the heart.”biblegateway.com. Similarly, Jesus in the Gospels teaches that on the Last Day “there is nothing hidden that will not be made known” – the very concept Al-ʿĀdiyāt conveys about secrets being revealed. These shared motifs underscore a common theological theme: no secret or deed can escape the sight of God, and a final divine justice will expose and recompense all actions and intentions.

- Human Ingratitude and Moral Behavior: The critique of human ungratefulness and worldliness is also mirrored in the Bible. In the Torah, for example, Moses rebukes the Israelites’ ingratitude after God’s blessings. Deuteronomy 32:15 uses striking language akin to the Qur’anic kanūd: “But Jeshurun (Israel) grew fat and kicked… then he forsook God who made him and scoffed at the Rock of his salvation.”biblehub.com Here, as in Al-ʿĀdiyāt, prosperity led to spiritual complacency and thanklessness. The Quranic condemnation of chasing wealth at the expense of faith finds a parallel in the New Testament warning: “For men shall be lovers of their own selves, lovers of money… unthankful, unholy.” (2 Timothy 3:2)biblestudytools.com. Both scriptures identify greed and ingratitude as hallmark vices of godlessness. Moreover, the metaphor of the war horse can be intriguingly compared to the Hebrew Bible’s own descriptions: in the Book of Job, God speaks of the warhorse: “It paws fiercely, rejoicing in its strength… It laughs at fear, afraid of nothing; it does not shy away from the sword.”web.mit.edu. This is not to say Job and Al-ʿĀdiyāt address the same topic, but the imagery of the valiant horse is common to both, symbolizing courage and devotion. The Qur’an uses it to shame man’s ingratitude, while Job uses it to illustrate God’s creation marvels – yet in both cases the horse serves as a moral exemplar of sorts, highlighting by contrast the failure of some humans to live up to that courage or loyalty.

- Divine Knowledge of the Heart: The Quran’s stress that God knows what is hidden in the breasts finds parallel emphasis in the Bible’s teaching that only God fully knows the human heart. King David prays, “Shall not God search this out? For He knows the secrets of the heart” (Psalm 44:21)biblegateway.com. And Jesus’ disciple Peter acknowledges, “Lord, You know all things; You know that I love You,” appealing to God’s knowledge of the heart beyond outward evidence (John 21:17). In both traditions, this is a sobering and comforting truth: sobering because one cannot hide hypocrisy or ingratitude from God, comforting because God understands one’s true intentions and unseen struggles as well.

In comparative perspective, Surah Al-ʿĀdiyāt reinforces themes that are part of a universal biblical worldview: gratitude to God as a fundamental duty, the peril of letting material wealth corrupt one’s soul, the certainty of a coming judgment when all secrets are revealed, and the unwavering justice and omniscience of the Creator. Each tradition might frame these themes with its own emphasis – for example, the Qur’an uses the stark oath and accusation format, while the Bible often uses narrative or parable – but the moral and theological substance often converges. Such parallels can be used in interfaith reflection to appreciate how the Qur’an’s message “challenges or affirms” earlier scripture. For instance, a Jewish or Christian reader might see Al-ʿĀdiyāt as affirming the Old Testament lesson that prosperity should lead to thanksgiving not pride, or a Christian might see it as harmonizing with Jesus’ teaching that “where your treasure is, there your heart will be also” – hence if one’s treasure is only on earth, the heart has gone astray.

Conclusion: Though brief in length, Surah Al-ʿĀdiyāt packs a profound punch through its layered use of imagery and meaning. Scientifically and historically, it transports us to the dust-laden dawn of an Arabian battlefield, attesting to the Qur’an’s grounded realism. Philosophically, it forces an examination of human morals – urging us to rise above our lower instincts of ingratitude and greed. Theologically, it connects with core Islamic tenets of God’s justice and knowledge, while resonating with scriptural themes familiar in Judeo-Christian thought. The war horses of Al-ʿĀdiyāt thunder across the ages with a timeless call: Remember your true Master with gratitude and devotion, for all that is hidden will one day be laid bare. On that day, the loyalty of a humble beast might even put to shame the heedlessness of a human, unless we take to heart the lesson and redirect our love and zeal to where it truly belongs – in service of our Lord, with the hope of His mercy on Judgment Day.

Sources:

- The Qur’an, Surah Al-ʿĀdiyāt (100) – text and various translations.

- Tafsīr Ibn Kathīr (14th c.) – Commentary on Surah 100: reports from Companions on meaning of kanūd and other termsquran.comquran.com.

- Tafsīr al-Qurṭubī (13th c.) – Classical exegesis noting linguistic insights (e.g., meaning of ḥuṣṣila in verse 10)quran.com and distinguishing general statements from the righteousislamicstudies.info.

- Maʿāriful Qur’ān by Mufti M. Shafi (20th c.) – Contemporary exegesis drawing from earlier scholars: explanation of oaths and analogy of horses vs. human gratitudeislamicstudies.info; definitions of Arabic termsislamicstudies.info; discussion on love of wealth and Rūmī’s parableislamicstudies.info; general lesson that prophets and true believers are free of the ingratitude describedislamicstudies.info.

- An Enlightening Commentary into the Light of the Holy Qur’an (modern Shiʿa tafsīr) – Provides historical context of a battle (Dhat al-Salāsil) associated with the surah according to Shiʿa traditional-islam.org, and philosophical discussion on whether man is innately ungrateful or has dual potentialal-islam.orgal-islam.org.

- Bible & Torah Parallels: Daniel 12:2 on resurrectionleaderu.com; Deuteronomy 32:15 on Israel’s ingratitudebiblehub.com; Psalm 44:21 on God knowing secretsbiblegateway.com; 2 Timothy 3:2 on future people being lovers of money and ungratefulbiblestudytools.com; Job 39:19-25 on the fearless warhorseweb.mit.edu; Hebrews 9:27 and Revelation 20:12 on judgment of the deadleaderu.com. These demonstrate the scriptural unity on themes of gratitude, moral responsibility, and divine justice across the Qur’an and earlier revelations.

Leave a comment