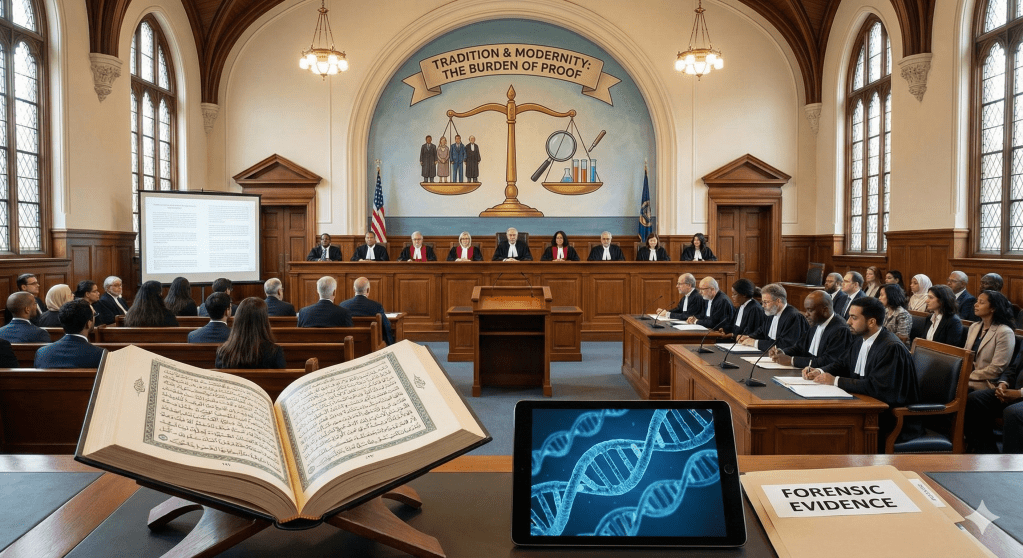

Epigraph

By the morning brightness and by the night when it grows still, your Lord has not forsaken you [Prophet], nor does He hate you, and the future will be better for you than the past; your Lord is sure to give you so much that you will be well satisfied. Did He not find you an orphan and shelter you? Did He not find you lost and guide you? Did He not find you in need and make you self-sufficient? So do not be harsh with the orphan and do not chide the one who asks for help; talk about the blessings of your Lord. (Surah Ad Duha or the Morning Brightness)

Written and collected by Zia H Shah MD, Chief Editor of the Muslim Times

In the Quran, Allah frequently employs oaths, swearing by various elements of His creation—such as the sun, the moon, time, and natural phenomena. These oaths serve multiple purposes, including emphasizing the significance of the ensuing message, highlighting the importance of the entities sworn upon, and directing attention to the signs of Allah’s majesty and power inherent in His creation.

Chapter number 91 of the Quran is named after the Sun or Al Shams and the chapter number 93 is named Ad Duha or the Morning Brightness. Today we will mostly focus on the latter. Surah Ad Duha starts with an oath: “By the morning brightness and by the night when it grows still.”

One primary function of these oaths is to underscore the gravity of the statements that follow. By swearing upon notable aspects of creation, Allah draws the reader’s or listener’s attention to the critical nature of the message. This rhetorical device is akin to asserting the truth and importance of the forthcoming discourse. For instance, in Surah At-Tur, Allah swears by the Mount, symbolizing the significance of the revelations given to Prophet Musa (Moses) on Mount Sinai. On other occasions the Quran swears on the sun, the moon, the constellations and many other parts of our universe.

The entities by which Allah swears are often remarkable signs within creation, reflecting His wisdom and artistry. By drawing attention to these elements, the Quran encourages contemplation of the natural world as evidence of divine majesty. For example, in Surah At-Tin, Allah swears by the fig and the olive, invoking both the fruits and their associated regions, which hold historical and spiritual significance.

Unlike humans, who are instructed to swear only by Allah due to His supreme status, Allah’s oaths by aspects of His creation serve to demonstrate His authority over all things. These oaths exemplify His dominion and the profound connection between the Creator and His creation. As noted in Islamic scholarship, “Allah swears by some of His creation because they are His signs and creation, so they are indicative of His Lordship, divinity, oneness, knowledge, might, will, mercy, wisdom, greatness, and glory.”

By swearing upon various elements of the natural world, the Quran invites believers to reflect upon these signs and recognize the underlying messages. This approach encourages deeper contemplation of the universe and one’s place within it, fostering a greater appreciation for the Creator’s wisdom and the interconnectedness of all things.

In summary, the oaths in the Quran serve as powerful rhetorical devices that emphasize the importance of the conveyed messages, highlight the significance of the entities sworn upon, demonstrate Allah’s supreme authority, and invite believers to reflect upon the signs present in creation.

So, why does the Quran swear on the sun or the morning brightness?

Scientific Wonder

The Sun, our closest star, is a massive sphere of hot plasma that serves as the primary source of energy for our solar system. Its immense gravitational pull governs the orbits of planets, asteroids, and comets. At the core of the Sun lies the powerhouse of its energy production: nuclear fusion.

Nuclear fusion is the process by which light atomic nuclei combine to form a heavier nucleus, releasing substantial energy in the process. In the Sun’s core, where temperatures reach approximately 15 million degrees Celsius, hydrogen nuclei (protons) undergo fusion to form helium. This process occurs in several steps known as the proton-proton chain reaction:

- Proton-Proton Fusion: Two protons collide and fuse, resulting in a deuterium nucleus (one proton and one neutron), a positron, and a neutrino.

- Formation of Helium-3: The deuterium nucleus fuses with another proton, producing a helium-3 nucleus (two protons and one neutron) and releasing gamma radiation.

- Formation of Helium-4: Two helium-3 nuclei collide, forming a helium-4 nucleus (two protons and two neutrons) and releasing two protons.

This fusion process converts mass into energy, as described by Einstein’s equation E=mc^2, and is responsible for the Sun’s luminosity and the heat and light it emits. Sun supplies all of earth’s energy needs directly or indirectly from a distance of 92 million miles that light takes 8 minutes to reach us on planet earth from its source the sun.

The energy produced in the core migrates outward through the radiative and convective zones before reaching the photosphere, from where it radiates into space as sunlight. This energy supports life on Earth, drives weather patterns, and influences the climate.

For the last century humanity is trying to mimic the sun for safe energy production on our planet but to no avail yet. Can the miracle that has been supplying for the last 4.5 billion years be called a fluke or an accident?

Historical Context

Revelation During a Period of Distress

Surah Ad-Duha (The Morning Brightness) was revealed in Makkah during an emotionally difficult period for Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him). After the initial series of revelations, there was a sudden pause in the coming of new verses. This fatrah (gap in revelation) lasted long enough that the Prophet became anxious and distressed. He deeply missed the solace of the Divine message, and feared that perhaps he had displeased Allah in some way. During this time, the Prophet’s enemies seized the opportunity to mock and taunt him. According to authentic narrations, a pagan woman (identified in some reports as Umm Jamil, the wife of Abu Lahab) sneeringly said, “O Muhammad, I think your ‘devil’ has finally left you.” Others sarcastically quipped that Allah had abandoned him. These cruel remarks compounded the Prophet’s grief, as he already felt the weight of wahy (revelation) having ceased temporarily.

Divine Reassurance and Strengthening Resolve

It was in this context of anxiety and yearning that Surah Ad-Duha was revealed as a profound reassurance. The entire chapter was meant “to relieve him of these negative feelings and to give him hope, positivity, and the assurance that Allah is with him no matter what.”

The opening verses gently swear by the bright morning and the still night, then deliver the comforting message: “Your Lord has not forsaken you, nor is He displeased.” This declaration directly refuted the idea that Allah had “forgotten” the Prophet. Instead, it affirmed Allah’s continuous care and love. The revelation of Ad-Duha lifted the Prophet’s spirits and renewed his determination. It assured him that the temporary silence did not signify abandonment, but was part of the divine wisdom. Classical scholars note that just as day and night alternate without implying Allah’s pleasure or anger, likewise the coming and going of revelation was not due to divine displeasure but due to Allah’s wisdom and timing. In fact, the Surah promised the Prophet that greater things lay ahead, strengthening his resolve to persevere. Thus, Ad-Duha served as a turning point – transforming the Prophet’s moment of grief into an occasion of hope and steadfastness, and reminding him (and the believers by extension) that Allah’s support had been with him in the past and would continue in the future.

Linguistic Analysis

Key Words and Phrases

The Surah begins with two powerful oaths: “By the morning brightness (al-ḍuḥā), and by the night when it covers with darkness (idhā sajā)” (93:1-2). The word “ḍuḥā” refers to the radiant morning light after sunrise. It evokes the image of the day’s bright, gentle warmth – a time often associated with hope, activity, and optimism. In contrast, “sajā” in Arabic means tranquil or still. Describing the night as “when it is still” suggests a deep calm and darkness that falls when most of the world is at rest. The pairing of these terms – bright day and quiet night – is rhetorically significant. It presents polar opposites that together encompass the full spectrum of time and human experience. This contrast also mirrors the Prophet’s emotional state: the light of inspiration versus the darkness of seeming isolation. Such juxtaposition sets a tone of contrast and change, subtly implying that just as morning follows night, the Prophet’s period of trial would be followed by joy and enlightenment.

The oath formula itself (“By the morning… and by the night…”) carries a classical emphatic function. In the Quran, Allah swears by magnificent creations to draw attention to the truths that follow and to encourage reflection. Here, swearing by morning and night serves to highlight the lesson that the subsequent verses will impart. It grabs the listener’s attention and hints that the coming message – of Allah’s care and promise – is as assured as the cycle of dawn after dusk. It also creates an emotional ambience: the listener can feel the relief of dawn and the stillness of night, preparing them for words of comfort.

When the Surah moves to its central message, it uses direct address and negation for emphasis: “Mā waddaʿaka Rabbuka wa-mā qalā” – “Your Lord has not forsaken you, nor does He hate you” (93:3). The verb “waddaʿa” comes from tawdīʿ, meaning to bid farewell or leave behind. Allah emphatically declares He has not abandoned the Prophet. Similarly, “qalā” means to detest or hate – a strong word rarely used in Quran. Allah assures that He does not hate or resent His Messenger. The double negation (“neither forsaken nor hated”) is a powerful rhetorical construction: it categorically denies any notion of Allah’s displeasure. The personal pronoun “your Lord” (rabbuka) adds intimacy – your caring Master has never left you. These linguistic choices convey a tender, emphatic reassurance. One can almost sense a loving tone in the original Arabic, as if soothing the Prophet’s heart.

Another key phrase is in verse 4: “Walal-ākhiratu khayrun laka mina l-ūlā” – “Surely the latter (state) is better for you than the former” (93:4). The term “ākhirah” can mean the Hereafter, and “ūlā” “the first (life).” Many exegetes interpret this as: the life to come is far better for the Prophet than this worldly life. This reminds him (and us) that any worldly hardship is temporary, and eternal bliss awaits, which is immensely superior. However, ākhirah may also be understood as later times and ūlā as earlier times. In that sense, it is a promise that the future of the Prophet’s mission will be better than its beginning. Both meanings are valid and complementary: ultimately, the Prophet’s afterlife in Paradise will indeed outshine all earthly experiences, and the coming years of his prophethood will bring victories easing the struggles of the start. The verse’s wording cleverly encompasses both spiritual and temporal optimism. It instills hope that better days are ahead, both in this world and the next.

In verse 5, Allah further promises: “Wa la-sawfa yu’ṭīka Rabbuka fa-tarḍā” – “And soon your Lord will give you, and you shall be satisfied.” The construction “la-sawfa” (indeed, soon) adds certainty and near expectation. Yet what will be given is left unspecified – an open-ended promise. This generality implies Allah will bestow abundant blessings of many kinds. The phrase “fa-tarḍā” (“then you will be pleased/satisfied”) is especially profound. It suggests that Allah will not cease giving until the Prophet is fully content. Classical commentators note that this encompasses the Prophet’s ultimate satisfaction in the hereafter, such as by granting him the greatest intercession. For instance, Imam Qurtubi relates that the Prophet responded to this verse by saying he would not be truly pleased “as long as a single member of my Ummah remains in Hellfire,” and Allah will grant him until he is pleased. This highlights the breadth of Allah’s promise – from the spread of Islam and victories in this life, to the Prophet’s personal joy at seeing believers forgiven in the next. Linguistically, ending the promise with fa-tarḍā (you shall be pleased) puts the focus on the Prophet’s happiness – a remarkable illustration of how dearly Allah regards His Messenger.

Verses 6–8 then employ a memorable rhetorical pattern: “Did He not find you… and [then] He…”. Three questions remind the Prophet of Allah’s past favors: “Did He not find you orphaned and give [you] shelter? Did He not find you lost (ḍāllan) and guide [you]? And did He not find you in need and enrich you?” (93:6-8). The interrogative “a-lam” (Did He not?) is not seeking information but affirming a known fact in a gentle, reflective way. It’s as if Allah is saying “Remember that indeed We did these things for you.” Each question is immediately followed by “fa…” (“then …”), indicating how Allah swiftly responded to the Prophet’s state with His grace. The repetition of this structure has a persuasive rhythm—reminding the listener of three clear examples of divine providence.

The wording of these favors is also carefully chosen. The Prophet is reminded that he was born “yatīman” (an orphan) and Allah provided him care and protection. Historically, Muhammad’s father died before his birth and his mother died when he was six; yet he was lovingly raised first by his grandfather and then his uncle. The verse uses the verb “āwā” (gave shelter/refuge), indicating how Allah arranged guardians and homes for the young orphan. Next, “ḍāllan” in verse 7 has been interpreted in light of the Prophet’s status. Although ḍāll in a general sense can mean “astray” or “lost,” here it cannot mean the Prophet was astray in faith, since prophets are protected from misguidance. Instead, commentators explain it as “unaware” or “seeking” – the Prophet was looking for truth but had not yet been given revelation. Allah found him in that state and “guided” him by granting prophethood and scripture. In support of this, the Quran elsewhere addresses the Prophet: “You did not know what the Book or faith was, but We made it a light by which We guide whom We will.”

Some scholars also note that ḍāll can mean “lost” in the sense of not being recognized by people. The Prophet lived in a society lost in idolatry; people did not know his rank. Allah then guided people to him, making his message known. In either case, the word is not a criticism but a description of Allah’s guidance coming at the right time. Finally, Allah recalls finding the Prophet “ʿāʾilan” – in a state of need or poverty – and then enriching him (fa-aghnā). The young Muhammad was not from a wealthy family; as an adult too he experienced times of financial constraint. Allah enriched him, for example, through his marriage to Khadijah – a wealthy, noble woman who supported him – and by giving him contentment and self-sufficiency of the soul. Indeed, the Prophet said, “True wealth is not in abundance of possessions, but being rich in soul (contentment).”

Thus “enriching” can mean Allah made him independent of need and satisfied with what he had. The Arabic term “aghnā” can imply spiritual richness as well as material sufficiency, and both were fulfilled in the Prophet’s life.

Overall, the language of Surah Ad-Duha is gentle, poignant, and layered with meaning. The oaths create a vivid backdrop of light and dark, the direct address and negation in verse 3 dispel the clouds of doubt, and the rhythmic questions in verses 6–8 stir gratitude by recalling personal history. The surah’s diction conveys Allah’s intimate care for His Prophet. Even without knowing the context, a reader of the Arabic can feel a soothing cadence and positive arc: it starts in the soft light of morning, traverses a period of darkness, then affirms love and promise, and ends by urging kindness and thankfulness. These linguistic elements together set a tone of compassionate reassurance.

Thematic Insights

From Perceived Abandonment to Divine Assurance

A central theme of Surah Ad-Duha is the shift from an initial sense of abandonment to a strong assurance of Allah’s nearness. At the start, the Prophet had felt as if he was left alone (due to the pause in revelation), a feeling his enemies tried to reinforce with their mockery. The very first message Allah gives in this Surah is an emphatic negation of that notion: “Your Lord has not forsaken you nor is He displeased” (93:3). This marked a dramatic turning point. In place of perceived distance, Allah asserts His closeness and approval. Thematically, this teaches that Allah’s care has been there all along, even when one feels it less. The pause in revelation was a test, not a termination of the relationship. By swearing on the calming phenomena of dawn and night, Allah seems to say: just as morning light returns after darkness, My guidance and favor to you were never gone; they are returning with an even brighter message. The Prophet’s moment of anxiety is directly addressed by Allah’s gentle words, removing any doubt about Allah’s love for him. This transition from despair to hope illustrates a broader spiritual lesson: a believer may sometimes feel desolate or that their prayers are unanswered, but Allah’s support is in fact ever-present and will manifest again in due time. The tone of the Surah itself reinforces this – moving from a somber, reflective mood to an uplifting, optimistic one. By the end of the third verse, the initial worry is entirely dispelled by divine reassurance.

Past Hardship and Future Ease

Another major theme is the contrast between past difficulties and future blessings, highlighting a trajectory from hardship to ease. Allah explicitly tells the Prophet that what is coming is better than what has passed. On one level, as classical and modern scholars note, this pointed to the Prophet’s future victories in his mission. In the early Makkan period, Muslims were few and oppressed, and the Prophet faced rejection. The promise that “the latter period is better” foretold the eventual spread of Islam and the nascent community’s success after years of struggle. This indeed came true – within a decade or two, the Prophet saw Islam triumph in Arabia, confirming the prophecy of this verse. On another level, the verse comforts by pointing to the ultimate future: the Hereafter. However challenging life may be, the reward with Allah is far greater and everlasting. This perspective gave the Prophet (and gives all believers) a sense of patience and purpose. Any present hardship is put into context – it is neither permanent nor pointless. In fact, difficulty is often a precursor to ease, just as the dark night is a prelude to a brilliant morning. Although Ad-Duha doesn’t state it explicitly, it aligns with the general Quranic principle “Indeed, with hardship [will be] ease” (94:6).

The Surah then reinforces this theme by prompting the Prophet to remember how Allah has already brought him through past hardships. The rhetorical questions in verses 6–8 enumerate earlier stages of the Prophet’s life that were challenging, and how Allah alleviated them. He was an orphan – a situation of vulnerability – and Allah arranged loving guardians for him. He was searching for truth in a society of ignorance, and Allah granted him guidance and prophethood. He experienced poverty, and Allah provided for him and made him content. By reminding him of these personal examples, Allah is effectively saying: “Just as I helped you then, I will continue to help you now and in the future.” This reflection on the past builds trust in future ease. It’s a powerful thematic lesson in gratitude and optimism: remembering past blessings can strengthen one’s faith that current or future difficulties will also be resolved by Allah’s grace.

Notably, the contrasts in the Surah are very touching: orphanhood vs. care, unawareness vs. guidance, poverty vs. sufficiency. Each pair shows a journey from a state of lack to a state of fulfillment. The pattern implies that Allah’s way is to gradually uplift His servants, filling the voids in their lives with His bounty. For the Prophet, this was true in the literal sense. But thematically, it extends to all believers: the dark moments in our lives are often followed by relief and improvement. Sometimes the “delay” in help (like the delay in revelation) is only to teach patience or to make the eventual relief even more meaningful. Thus, Ad-Duha instills a sense of tawakkul (trust in Allah’s plan). It teaches that a believer should never lose hope due to a temporary downturn. The future holds something better by Allah’s will, especially if one remains steadfast. And ultimately, even if some struggles last a lifetime, the ākhirah (Hereafter) will abundantly compensate for every pain, being “far better” than this transient world. The Prophet exemplified this outlook: he remained optimistic and committed to his mission after this revelation, confident in Allah’s promise of eventual victory and eternal reward.

Gratitude and Social Responsibility

In its concluding verses, Surah Ad-Duha shifts to a practical moral directive, connecting gratitude to social responsibility. After reminding the Prophet of how Allah helped him, Allah instructs him on how to express thankfulness for those blessings: “So as for the orphan, do not oppress him. And as for the petitioner (beggar), do not repel him. And as for the favor of your Lord, proclaim it.” (93:9-11). These three commands encapsulate a call to action in response to Allah’s grace.

First, kindness to orphans: “Therefore, do not maltreat the orphan.” The use of fa- (“so/therefore”) ties this command directly to the preceding reminder “[Allah] found you an orphan and gave you shelter”. In other words, because Allah protected you when you were an orphan, you must care for orphans with compassion. The word “taqhar” (translated as oppress or harshly subdue) implies not to overpower the orphan or treat them with harshness or humiliation. Instead, classical commentators like Qatādah said, “Be like a merciful father to the orphan.”

This instruction institutionalizes empathy – the Prophet (and by extension all of us) should remember our own past hardships and pay it forward by protecting those who are now in that vulnerable position. The thematic message is clear: true gratitude for Allah’s blessings is shown by helping others who are in need, not by boasting or mere words.

Second, charity and respect for the needy: “Do not repel the petitioner.” The term “as-sāʾil” means one who asks – it can mean someone asking for material help (a beggar), or someone asking for guidance or knowledge. Both interpretations are given in classical exegesis. If it is a beggar, the verse means not to scold or drive away anyone who asks for help. Rather, a believer should respond kindly and, if possible, give from what Allah has given them. This again ties to the earlier verse: the Prophet was in need and Allah enriched him, so he should not ignore those in need. If “sāʾil” is taken more broadly as any seeker (even a student of knowledge asking a question), the meaning would be: do not turn away someone who seeks something good from you. The Prophet indeed was extremely generous both with wealth and with teaching; he never turned away a sincere questioner. In either case, the verse emphasizes generosity, approachability, and compassion towards people who ask for our assistance. It is a call to social mercy – to treat the disadvantaged with dignity. As one commentary puts it, “respond to the poor with mercy and gentleness.”

This instruction complements the first: where the first focuses on not oppressing the weak, this focuses on actively helping and respecting those who seek help.

Finally, proclaiming the blessings of Allah: “And as for the blessing of your Lord, then speak about it.” The word “ḥaddith” (recount, declare) in context means to acknowledge and broadcast Allah’s favor. For the Prophet Muhammad, the greatest blessing was the revelation and prophethood itself. Thus, this verse is an encouragement to continue preaching the message – to announce the Qur’an and guidance that Allah has given. It also implies thanking Allah openly for His bounties. In a hadith the Prophet said, “Whoever is not thankful to people is not thankful to Allah.” – meaning gratitude should be expressed, not kept hidden. Hadith here is in the sense of speaking about a blessing. Therefore, the Prophet is told to celebrate Allah’s grace by sharing it: both by conveying the revelation to humanity and by generally praising Allah for His kindness. In a personal sense, to “proclaim God’s favor” also guards one against despair or ingratitude. It means deliberately focusing on the positive – counting one’s blessings and attributing them to Allah. This is the final antidote to the earlier worry that “Allah has abandoned me” – instead of that negative thought, one should actively remember and mention how Allah has blessed me. Such grateful proclamation solidifies one’s faith and spreads positive awareness to others as well.

Together, these three instructions form a coherent theme: Gratitude must translate into compassionate action. The Surah doesn’t end merely by comforting the Prophet; it ends by guiding him on how to live out the lessons of that comfort. He is consoled that Allah never forsook him – so he must never forsake the orphans. He is told Allah will give him abundance – so he should give to those who ask. He is reminded of Allah’s blessings – so he should spread hope and thanks. There is a beautiful symmetry here: each moral directive corresponds to one of the earlier mentioned favors. This structure teaches all believers that when Allah graces us, He expects us to “pay it forward” in goodness. The theological implication is that serving humanity, especially the vulnerable, is a form of shukr (thankfulness) to God. Moreover, speaking about Allah’s bounty (without pride or arrogance) is a way to honor the Giver and inspire others.

In essence, Ad-Duha moves from the internal (the Prophet’s internal state of distress and its alleviation by Allah’s words) to the external (actions to be done in society). It begins by healing the heart and ends by motivating the hands and tongue towards righteousness. This thematic flow underscores a holistic message: believers should find solace in Allah’s care, remain hopeful for the future, remember past blessings – and let that gratitude spur them to benevolence and praise. It’s a succinct yet comprehensive guide for a grateful life. As one commentary concludes, Allah instructs the Prophet to treat others with the same love and kindness that Allah had shown him, as a way of “repaying and rendering thanks for the favors” his Lord bestowed.

Classical Interpretations

Classical scholars of Quranic exegesis (tafsir) have offered rich commentary on Surah Ad-Duha, delving into its context, language, and theology. We find remarkable consensus on the core message, along with diverse insights. Here are perspectives from four renowned commentators:

- Ibn Kathir (d. 1373 CE) – In his Tafsir al-Qur’an al-‘Azim, Ibn Kathir highlights the * سبب النزول* (reason for revelation) of Ad-Duha. He cites the hadith of Jundub ibn Sufyan: when the Prophet fell ill and could not pray at night for a couple of nights, a woman mockingly said, “I think your Satan has left you.” This prompted the revelation of “By the forenoon, by the night when it grows dark, your Lord has not forsaken you nor does He hate you.” Ibn Kathir underscores that Allah never abandoned His Messenger. On the verse “the Hereafter is better for you than the first life,” he remarks that the Prophet was offered the choice of worldly immortality or meeting Allah, and he chose Allah – illustrating that his focus was always on the better abode of the Hereafter. Regarding “your Lord will give you and you will be satisfied,” Ibn Kathir, like many others, connects it to the Prophet’s special status in the afterlife. He notes it implies Allah will grant the Prophet’s intercession and other honors until the Prophet is pleased with the fate of his followers. Ibn Kathir even mentions the River Kawthar in Paradise and other bounties prepared for Muhammad as part of this promise. On verses 6-8, Ibn Kathir explains each favor: Allah found him orphaned and arranged shelter (referring to the care of Abdul Muttalib and Abu Talib), found him unaware of prophethood and gave guidance (through revelation), and found him poor and enriched him (through trade via Khadijah’s wealth and by contentment). For the final verses, Ibn Kathir stresses doing good in response: “just as you were an orphan and Allah sheltered you, then do not oppress the orphan… just as you were in need of guidance and Allah guided you, do not scorn the seeker… just as you were poor and Allah enriched you, then proclaim Allah’s favor”. Thus, Ibn Kathir sees the Surah as both a comfort to the Prophet and an exhortation to noble character, reflecting Allah’s past grace in future behavior.

- Al-Tabari (d. 923 CE) – The eminent early commentator Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari provides a thorough account of transmitted reports about this Surah. In his Jāmiʿ al-Bayān, he records the same background: that after a gap in revelation, the idolaters said, “Muhammad’s Lord has forsaken him.” Tabari includes the report from Ibn ‘Abbas that the Prophet became distressed when Jibril did not visit him for several days, and pagans said his Lord disliked him, whereupon Ad-Duha was sent down. He examines the meanings of key words, often citing early authorities like Mujahid and Qatadah. For example, on “wa-l-layli idhā sajā,” he notes Mujahid’s interpretation that sajā means “stilled” or “darkened”, describing the night’s stillness. Tabari’s commentary on “wa-wajadaka ḍāllan fahadā” compiles various understandings. He explicitly rejects any reading of “ḍāll” that would imply the Prophet was astray in faith. Instead, he favors the meaning “lost to your people and unknown, then Allah guided them to you”, as well as the idea that the Prophet did not know scripture and faith until Allah guided him. These interpretations are supported by Quranic evidence and do not impugn the Prophet’s integrity. Tabari often concludes by choosing the interpretation that best fits the context and Arabic usage. Theologically, he underscores Allah’s care in the Prophet’s life; for instance, when explaining “did He not find you an orphan and give you shelter,” Tabari highlights Allah’s arrangement of the Prophet’s guardians and how that fulfilled this verse. He also addresses an interesting practice: some early Muslims would say “Allāhu Akbar” at the end of this Surah (and others) in prayer, based on reports that the Prophet taught such separation between certain surahs. (Tabari himself did not find a strong basis for requiring this, but he notes the narrations). Overall, Tabari’s exegesis firmly situates Ad-Duha as a testament to the Prophet’s esteem in Allah’s sight and as a reminder of Allah’s consistent grace. He often concludes the discussion by returning to the main point: “Your Lord has not forsaken you” – emphasizing that every line of the Surah reinforces Allah’s favor upon Muhammad.

- Al-Qurtubi (d. 1273 CE) – The Andalusian scholar Imam Al-Qurtubi, in his al-Jāmiʿ li-Aḥkām al-Qur’ān, also covers the revelation context and linguistic nuances. Qurtubi relates the same incident of Umm Jamil’s taunt and the subsequent revelation of Ad-Duha, citing it as a known سبب نزول. He delves into the Arabic grammar and rhetoric: for instance, he explains that the oaths by dawn and night are meant to comfort the Prophet by these signs of nature – that just as these cycles are normal, so was the temporary pause in revelation, not an abandonment. On “mā waddaʿaka… wa mā qalā”, Qurtubi points out the eloquence: Allah negated both abandonment and loathing, covering any possible negative thought. He also mentions that qalā (hate) is a strong term, used here to emphatically deny that Allah hates His Prophet in the least. Qurtubi pays special attention to verse 5 (“your Lord will give you so that you will be satisfied”). He records the beautiful response of the Prophet that he would not be satisfied if even one of his followers remained in Hell – indicating the Prophet’s vast mercy. Qurtubi sees this as an implicit promise of the Prophet’s shafā‘ah (intercession) being accepted, and Allah ultimately saving many believers to please His Messenger. This, Qurtubi says, is one of the honors hinted at in the Quran without being explicitly spelled out. On verses 6-8, Qurtubi, like others, stresses the literal truth of each statement in the Prophet’s life. He often brings in hadith or historical reports – for example, he notes how Abdul Muttalib once said he never let Muhammad (as a child) out of his sight, indicating how Allah placed special care in the hearts of his guardians. In discussing “found you poor and made you rich,” Qurtubi cites opinions that this refers to Khadijah’s wealth or to contentment, and he leans on a hadith: “richness does not mean having many possessions, but being content with oneself,” to clarify it’s not about opulent wealth. In the final verses, Qurtubi emphasizes the ethical commands. He echoes the interpretation of “do not repel the petitioner” as not rebuking one who asks for help or knowledge, and he quotes early scholars who said this includes not turning away the poor beggar empty-handed – at least speak kindly to them. Qurtubi also mentions a legal point: from “proclaim the bounty of your Lord,” some scholars derive that verbally thanking Allah and publicizing His blessings is recommended, as long as it’s not boastful. He relates a saying of the Prophet: “Talking about Allah’s blessings is gratitude (shukr), and ignoring them is ingratitude (kufr).” In summary, Al-Qurtubi’s interpretation reinforces the tender care Allah had for His Prophet and the corresponding duty of the Prophet (and all grateful believers) to care for others. Theologically, he sees in this Surah a proof of the Prophet’s high rank (refuting anyone who thought Allah was upset with him) and an encouragement for the Prophet to continue his mission with full trust in Allah’s plan.

- Fakhr al-Din al-Razi (d. 1209 CE) – Known as “the Imam of commentators” for his extensive Mafātīḥ al-Ghayb (Tafsir al-Kabir), Al-Razi offers deep analysis on Ad-Duha. Razi often explores multiple dimensions of meaning. On the oaths by the morning and night, he philosophizes that Allah swore by these times to indicate the wisdom of both states – light and darkness each have benefits – and similarly the presence or absence of revelation each had a wise purpose. He argues that continuous daylight would overwhelm creatures, so night provides rest; analogously, if revelation had been incessant without pause, it might have overwhelmed the Prophet’s community, so the pause was by divine wisdom. Razi also addresses possible objections. For example, he vigorously refutes any literal interpretation of “ḍāll” (lost) that would contradict the Prophet’s protection from error. In fact, Razi famously compiled almost twenty different interpretations for “wa-wajadaka ḍāllan fahadā” to demonstrate the range of acceptable meanings that do not impugn the Prophet. He cites opinions such as: “You were lost to your people and Allah guided them to you,” or “You were engrossed in love of Allah and away from worldly ways, and Allah guided people through you,” or simply that “You did not know the Scripture and faith until We guided you to it,” referencing Qur’an 42:52. By listing many views, Razi shows that ḍalāl (when attributed to the Prophet here) can mean “being unaware of something” or “lacking instruction until it came”, rather than misguidance. This scholarly exercise by Razi upheld the doctrine of prophetic infallibility while allowing the Quran’s words their proper linguistic scope. On the promise that the Prophet’s future will be better, Razi notes it encompasses both worldly triumphs and spiritual elevations. He muses that the Prophet’s every passing moment actually brought him closer to Allah, so indeed every later moment was better in nearness to God than before – a spiritual interpretation beyond the obvious historical one. Razi also discusses the Prophet’s ridā (satisfaction) mentioned in verse 5. He, too, mentions that the Prophet’s ultimate wish is the salvation of his Ummah, and that Allah will grant him the greatest honor of intercession. Razi ties this to the Prophet’s role as raḥmatan lil-‘ālamīn (mercy to the worlds), whose personal joy is linked to his community’s wellbeing. In his moral reflections, Razi often draws broader principles: from “do not oppress the orphan,” he extrapolates that one should never exploit the weakness of any vulnerable person – because Allah is the supporter of the weak and He supported the Prophet when he was weak. From “do not turn away the asker,” Razi extends it to mean one should be generous with knowledge as well: never turn away someone seeking guidance or answers about faith. And regarding “proclaim the blessing,” Razi writes about the importance of recognizing blessings. He warns against the false humility of hiding Allah’s favor; instead one should use it for good and acknowledge Allah’s grace publicly, as this inspires gratitude in oneself and others. In sum, Al-Razi’s commentary is characteristically comprehensive – covering linguistic, theological, and spiritual angles. He sees Ad-Duha as an affirmation of the Prophet’s lofty status (refuting any hint of divine displeasure), a lesson in the ebb and flow of spiritual experiences (with the pause in revelation as a trial), and a reminder that with patience and trust, relief always comes. Razi’s theological takeaway is that Allah’s relationship with His beloved Prophet is one of unceasing care; any test is for wisdom, not withdrawal of mercy. And the ethical takeaway is that believers should emulate the Prophet in responding to Allah’s gifts by spreading mercy and guidance to others.

All these classical interpretations, despite their different styles, converge on viewing Surah Ad-Duha as a tender message from Allah to Prophet Muhammad. They affirm that the Surah highlights God’s constant grace, provides solace amidst trial, and carries implicit directives on how to live gratefully and charitably. In classical Islamic thought, Ad-Duha also had theological implications: it subtly refuted claims of the idolaters and established that Allah’s love for Muhammad is unwavering. It underscores the principle that a delay in divine help is not a denial. The commentators often point out how this Surah, though addressed to the Prophet in singular, carries universal morals for the community – especially about caring for orphans and the needy, given how often those themes recur in the Qur’an’s Makkan revelations. Thus, through the lens of these scholars, Ad-Duha is both a deeply personal reassurance to the Prophet and a chapter of broad guidance, embodying hope, gratitude, and benevolence as fundamental Islamic values.

Modern Reflections

Beyond its historical and classical exegesis, Surah Ad-Duha continues to inspire and console people in the modern world. Its psychological and spiritual lessons are strikingly relevant to contemporary struggles, making it a source of solace and motivation for many.

Emotional and Psychological Comfort: The revelation of Ad-Duha addresses feelings of despair, loneliness, and self-doubt – emotions that are all too common today. The Prophet (PBUH) experienced a form of what we might call spiritual grief or anxiety when he feared Allah’s word had stopped coming. Allah responded with compassion and reassurance. Modern readers take great comfort in knowing that even the best of creation went through a period of heaviness in the heart, yet Allah had not forsaken him. This teaches that feeling temporarily abandoned or depressed is not a sign of true abandonment. One lesson often drawn is that Allah’s love is constant, even when life’s circumstances make us feel otherwise. As one contemporary writer put it: Surah Ad-Duha was revealed to relieve the Prophet of negative feelings and to give him hope and positivity, assuring him that Allah is with him no matter what. In the same way, a believer who feels spiritually low or ridden by problems can find in this Surah a divine message of hope. It reminds us that “your Lord has not forsaken you” applies in our lives too – Allah doesn’t hate us or forget us, even if we face difficulties or don’t feel an immediate answer to our prayers.

From Darkness to Light – A Paradigm of Hope: The imagery of the morning brightness after the still night carries a psychological metaphor that modern commentators love to highlight. In times of depression or sorrow, one’s world can feel as dark and still as the dead of night. Ad-Duha opens by almost physically lifting one’s gaze: “By the morning light!” – effectively saying, look at the dawn, the world is not all darkness. Some have even advised that a person battling low mood should take this as a cue to literally seek out the morning sun – to reset their mindset and appreciate the daily renewal of hope. The next oath, “by the night when it grows calm,” is also interpreted in modern reflections as advice: the night’s purpose is rest, not anxiety. When depressed, people often suffer insomnia or an erratic sleep cycle; this verse can be seen as encouraging a healthy pattern – use the night for comfort and sleep, not for dwelling on sorrow. Such reflections show how the Surah speaks to mental health: it recognizes the rhythm of life – ups and downs – and urges us to work with that rhythm (embracing dawn’s hope and night’s rest) rather than succumb to unbalanced despair.

The promise “the future will be better than the past” is an antidote to the hopelessness that many experience in personal trials. When someone is depressed, they often feel nothing will improve. But Allah flatly tells us otherwise. As a comment on Reddit succinctly paraphrased: This ayah reminds us that life in this world is temporary and that the future – ultimately Jannah – will certainly be better, helping us view our problems as temporary tests.

Knowing that there is light at the end of the tunnel – whether in this life or the next – can inspire resilience. Therapists speak of “hope” as a crucial ingredient in overcoming depression; this Surah injects hope directly from the divine source. It teaches optimism as almost a requirement of faith.

Gratitude as a Tool for Resilience: Modern spiritual thinkers often emphasize the latter half of Ad-Duha as a blueprint for combating sadness through gratitude. Verses 6-8 prompt an individual to reflect on their own life story: “Has Allah not helped you before? Recall those moments.” In counseling, a practice similar to this is gratitude journaling or recalling past victories to gain confidence for the future. The Surah essentially does this for the Prophet by listing his past blessings. We can each do the same – remember times when we felt lost and then found a way, or times we were in need and then received relief. “When a person is depressed, giving them examples of how Allah has helped them in the past will strengthen their conviction in Allah’s promises for the future,” as one reflection notes. This aligns perfectly with modern positive psychology techniques that encourage focusing on past positives to build hope. After enumerating such blessings, Ad-Duha directs us to proactive gratitude: helping others and speaking of blessings. From a mental health perspective, helping those less fortunate is known to improve one’s own sense of well-being. The verse “So do not oppress the orphan” can be seen as telling someone who is down: go volunteer, help someone in need; it will shift your focus and make you realize you have purpose and relative fortune. In fact, the reflection we saw called this “the ultimate antidote to depression” – because it forces one to look beyond themselves to those who have it worse. Realizing “I still have many blessings others might lack” is a powerful way to break out of self-pity. Likewise, “do not turn away the beggar” reminds us of our material comforts – food, shelter, etc., which we often take for granted. By engaging with the needy, one recognizes the gifts one has, which fosters gratitude and a positive outlook. Modern readers frequently mention that verses 9-10 teach them to count their blessings and help the less fortunate as a means to feel better themselves. It’s a virtuous cycle: gratitude drives away despair, and helping others uplifts one’s own soul.

The final verse, “And proclaim the bounty of your Lord,” also resonates with people today. It encourages sharing positivity. Whether that’s in the form of telling others what you’re grateful for, doing dawa (inviting to the faith) by talking about how Islam or Allah’s guidance has improved your life, or simply maintaining an attitude of praise (dhikr), it helps keep a person’s faith upbeat. One writer explained, “This verse is about maintaining that renewed faith and bond with Allah – by pondering, glorifying, and talking about His blessings, whether in study circles, discussions with friends, or even on social media. Keeping the remembrance of Allah close to your heart will keep your spirits lifted.” In an age where negativity can spread so easily, Ad-Duha’s call to share goodness and gratitude is particularly relevant. It’s essentially telling us to be a beacon of positive faith, just as the Prophet was commanded to openly declare Allah’s favors (chiefly the Quran itself).

Relevance to Contemporary Struggles: Nearly everyone faces periods of uncertainty, loneliness, or failure – be it in personal life, career, or spiritual practice. Surah Ad-Duha speaks to those moments directly. Its message “Allah has not forsaken you” is extremely empowering for someone who feels their prayers aren’t being answered or who can’t feel the spiritual high they once did. Many people testify that reading and reflecting on Ad-Duha lifted them out of a dark place. It is often recommended as part of Islamic advice for anxiety and sadness. For example, the concept of the “Duha approach” to trauma has been discussed by modern scholars, suggesting that the Surah outlines steps to heal a troubled heart: Acknowledgment of pain, reframing the situation with hope, recalling past mercies, and then redirecting focus to helping others and staying positive. This approach can be applied to everything from personal depression to collective hardship. In times of community difficulties, leaders draw on Ad-Duha to remind people that Allah’s aid will come and that they should continue to care for the vulnerable meanwhile.

Moreover, Ad-Duha has been central in modern khutbahs (sermons) and lectures about overcoming feelings of worthlessness. The Prophet felt “maybe Allah does not want me as a prophet anymore” – an intense form of self-doubt – and Allah directly corrected that thinking. Believers today sometimes feel “I am such a sinner, maybe Allah hates me” or “My life is a mess, perhaps God is punishing/abandoning me.” Ad-Duha provides a divine rebuttal to that: Allah’s plan may include tests, but never assume that delays or hardships mean you are hated by Him. This is a crucial theological and psychological point. It replaces a destructive thought (“I’m forsaken”) with a constructive one (“There is wisdom, and Allah still cares”). Therapists would recognize this as cognitive reframing – and here the Quran itself is doing it for the believer’s mind.

Finally, the Surah’s emphasis on helping orphans and the poor continues to inspire Muslim charitable work. Many humanitarian campaigns invoke verses 9-10 to encourage donations, saying in effect: Remember where you or your Prophet came from, and share Allah’s blessings with those in need. Thus, the social impact of these verses remains strong: orphanages, care for refugees, and social welfare in Muslim communities often draw motivation from commands like those in Ad-Duha. This shows that the Surah not only soothes hearts but also moves hands into action in our modern context.

In conclusion, Surah Ad-Duha offers a timeless prescription for both spiritual and emotional wellness. Its key lessons – maintain hope in Allah’s mercy, recall past blessings, look forward to better outcomes, and show gratitude through kindness – are as meaningful today as ever. In personal moments of sadness or societal moments of crisis, Ad-Duha guides one back to a state of shukr (gratitude) and yaqīn (certainty) that Allah is with us. It transforms a mindset of “I am alone in the dark” to “My Lord will soon brighten my way.” This transformation of attitude, coupled with the call to serve others, makes Ad-Duha a profound source of solace and inspiration for resilience in the lives of countless Muslims. As the Surah itself exemplifies, after every hardship there is ease, and after every night, a glorious morning.

Epilogue

The Surah Ad Duha starts off with the cosmological argument, swearing on a part of God’s creation the sun and the morning brightness. Once the Creator, establishes Himself through His creativity, He then highlights His role in human history in bringing forth a destitute, an orphan, Muhammad, not only as successful merchant but now as an insightful preacher and prophet. In the last part of the Surah, He guides Muhammad himself and through him the rest of humanity, towards compassionate living in creating a society where the orphans, destitutes and have nots are taken care of without hurting their self-respect.

Sources

- The Noble Qur’an – Surah 93 (Al-Duḥā) with translations islamicstudies.info.

- Ibn Kathīr, Tafsīr al-Qur’ān al-ʿAẓīm (commentary on Surah Ad-Duha) honeyfortheheart.wordpress.com.

- Al-Ṭabarī, Jāmiʿ al-Bayān fī Tafsīr al-Qurʾān (early commentary) – reports from Ibn ʿAbbās, etc. on revelation context honeyfortheheart.wordpress.com islamicstudies.info.

- Al-Qurṭubī, Al-Jāmiʿ li Aḥkām al-Qur’ān – classical commentary (see commentary on 93:4-5 regarding intercession)quran.com.

- Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī, Mafātīḥ al-Ghayb (Al-Tafsīr al-Kabīr) – analytical commentary (discussion on the many meanings of 93:7) ijmmu.comijmmu.com.

- Ibn ʿAshūr, Al-Taḥrīr wa’l-Tanwīr – on the wisdom of the pause in revelation islamicstudies.infoislamicstudies.info.

- Islamqa fatwa 205660 – Explanation of why revelation paused and Surah Ad-Duha’s revelation islamicstudies.info.

- “Reflections from Surah Ad-Duha” – contemporary article highlighting its lessons on hope and gratitude reddit.com.

- The “Duha” Approach: Trauma and Islam – Yaqeen Institute (Tesneem Alkiek) – using Surah Ad-Duha as a model for healingthelionofallah.wordpress.com.

- Personal reflections and analysis (various authors) on the psychological benefits of Surah Ad-Duha reddit.com.

Leave a comment