Epigraph

He is the Mighty, the Forgiving; Who created the seven heavens, one above the other. You will not see any flaw in what the Lord of Mercy creates. Look again! Can you see any flaw? Look again! And again! Your sight will turn back to you, weak and defeated. (Al Quran 67:2-4)

He is Allah, the Creator, the Maker, the Fashioner. His are the most beautiful names. All that is in the heavens and the earth glorifies Him, and He is the Mighty, the Wise. (Al Quran 59:24)

Written and collected by Zia H Shah MD, Chief Editor of the Muslim Times

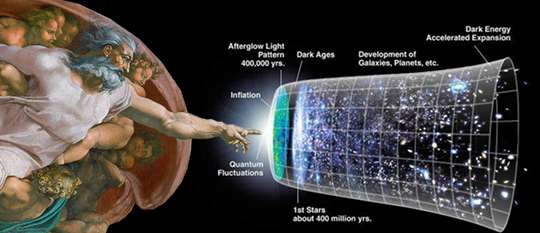

For decades, scientists have noticed that the fundamental parameters of our universe seem “just right” for life to exist. If certain physical constants or initial conditions were even slightly different, complex life (and perhaps any life) would likely be impossible. This remarkable observation is known as the fine-tuning of the universe. Many believe such fine-tuning is best explained by the existence of a purposeful Creator (God), while others propose alternative explanations like a multiverse or yet-unknown physical necessity. In this article, we will explore the fine-tuning concept from scientific, philosophical, and theological angles – examining the evidence and arguments on all sides – and consider whether it truly points to the existence of God.

Scientific Aspects of Fine-Tuning

Fundamental Constants “Just Right” for Life: Physics identifies several fundamental constants of nature that appear finely balanced to permit life. Small changes in these constants would produce a universe hostile to any complex structures. Key examples include:

- Cosmological Constant (Λ): This term in Einstein’s equations represents the energy density of empty space (dark energy). Its observed value is astronomically small – on the order of 10^−122 in dimensionless Planck units. Theoretical physics cannot yet explain why it isn’t much larger; in fact, naive quantum calculations suggest it should be 10^50 to 10^123 times bigger. If Λ were only several times larger than it is, the universe would have expanded so rapidly that galaxies and stars could not form. Conversely, if Λ were negative or too small, the universe might have recollapsed quickly after the Big Bang. The tiny, unexpected value of the cosmological constant allows a cosmos that develops galaxies, stars, planets, and life – a striking coincidence if due to chance alone.

- Gravitational Force: Gravity is set by Newton’s gravitational constant (and can be expressed by a dimensionless ratio N, the strength of electromagnetism vs. gravity). N is approximately 10^36, meaning electromagnetic forces inside atoms are 10^36 times stronger than gravity. If gravity were significantly stronger (or electromagnetism weaker), stars would burn much faster and smaller, likely leaving no time or stable environments for life. Stars might collapse into black holes or never form long-lived stable systems. If gravity were much weaker, stars and galaxies might not condense at all – the universe would remain a thin diffuse gas. In short, gravity’s strength relative to other forces lies in a narrow “habitable” range enabling a long-lived, structured universe.

- Strong Nuclear Force: The strong force binds protons and neutrons in atomic nuclei. If it were slightly weaker, atomic nuclei (especially larger ones) would not hold together, and elements heavier than hydrogen might not exist. With a weaker strong force, the periodic table would collapse to mostly hydrogen – no carbon, oxygen, or other essential elements for chemistry. If the strong force were slightly stronger, it would cause nearly all hydrogen to fuse into helium in the early universe (or in the first moments of the Big Bang). That would leave no hydrogen for water and no long-lived stars, and it would drastically reduce the diversity of chemistry available. Calculations show that a change of just a few percent in the strong force’s strength (relative to electromagnetism) would render a universe devoid of either hydrogen or of elements like carbon and oxygen. (Notably, some studies suggest up to a 50% increase might still allow hydrogen, but beyond that life chemistry fails.)

- Electromagnetic Force (Fine-Structure Constant): The electromagnetic interaction is characterized by the fine-structure constant α≈1/137. This number governs how strongly electrons bind to atoms and how chemical reactions occur. If α were significantly smaller, electrons would not bind well to nuclei, and atoms might not form stable structures. If α were larger, electromagnetic repulsion between protons would hinder nuclear fusion in stars and could disrupt stable atoms. For example, if electromagnetism were too strong relative to the strong force, no elements heavier than hydrogen would form, and stars might be unable to shine steadily. Conversely, if it were too weak, stars might collapse or atomic chemistry might be too feeble. Thus, α must also lie in a life-friendly range, tuned in concert with the strong force and other constants.

- Other Examples: Dozens of other parameters show similar sensitivity. The ratio of the proton’s mass to the neutron’s mass affects whether hydrogen fuses or decays – a slight difference could leave the universe with only neutrons or only protons. The “density parameter” Ω (overall mass-energy density of the universe) had to be extremely close to 1 in the early universe for structure to form – if the Big Bang’s initial expansion rate differed by more than ~1 in 10^15, the universe would either have collapsed or expanded too fast for galaxies to form. Even the entropy of the universe (disorder) had to start extraordinarily low; mathematician Roger Penrose calculated that the odds of our universe’s low-entropy beginning occurring by chance are about 1 in 10^10^123 – an absurdly tiny probability. Such examples have led researchers to conclude that life-permitting universes occupy an incredibly small fraction of possible physical parameter space.

Chance vs Design – How (Un)Likely is a Life-Friendly Universe? Given these examples, scientists have tried to quantify how unlikely our life-supporting universe would be if its parameters were randomly assigned. While we can’t know the actual probability distribution of fundamental constants, estimates of the allowed range for life are astonishingly narrow. As one analogy, the chance of all the physical “dials” being randomly set just right is like surviving a firing squad of fifty expert marksmen – theoretically possible by luck, but so improbable that design seems a more sensible explanation. Physicist Paul Davies noted “the impression of design is overwhelming” when one considers the many “coincidences” needed for life. Sir Fred Hoyle, a once-staunch atheist, famously remarked that “a superintellect has monkeyed with physics, as well as with chemistry and biology,” because the facts seemed to him to almost forbid a merely chance origin. In scientific literature, this fine-tuning is well-documented. The real debate is not whether the universe is fine-tuned for life (many agree it is), but rather what this fine-tuning implies about reality.

Modern cosmology has no accepted natural reason why constants take these life-permitting values – they are not fixed by any known theory and could conceivably have been otherwise. Because of this, fine-tuning is a central question that straddles science and philosophy. Does the uncanny suitability of cosmic physics for life point to an intelligent Designer (God) who set the “dials” appropriately? Or could it be explained by a lucky draw among countless universes, or perhaps by an undiscovered principle that forces the constants to be life-friendly? We turn next to the philosophical arguments that grapple with these questions.

Philosophical Aspects of the Fine-Tuning Argument

The Teleological Argument Updated: The fine-tuning argument is essentially a modern form of the Teleological Argument (the argument from design or purpose). Classical teleology dates back to thinkers like William Paley, who compared the world to a watch – just as a watch’s intricate order implies a watchmaker, the intricate order in nature implies a Designer. Fine-tuning shifts this analogy to the fundamental level of physics. It observes that the universe as a whole has precise conditions enabling life, and infers that a purposeful Mind best explains this “cosmic calibration.” In logical form, the argument notes that: (1) The universe’s life-permitting conditions are enormously improbable under random chance (or under any “atheistic” single-universe assumption). (2) If a divine Creator set the constants intentionally (design hypothesis), it isn’t surprising that they fall in the narrow life-permitting range – because such a Creator wanted life to emerge. (3) Thus, the fact we observe fine-tuning is said to strongly favor design over chance. Philosopher Richard Swinburne, for instance, argues that it is far more probable that God would create a life-sustaining universe than that such a universe would exist by accident; hence fine-tuning is evidence for God. Another proponent, Robin Collins, emphasizes that of the three main options – physical necessity, chance, or design – only design provides a satisfying explanatory reason for why these fundamental numbers all reside in the minuscule life-friendly interval.

Anthropic Principle – Selection Bias or Explanation? A key counterpoint in philosophy is the Anthropic Principle, which comes in “weak” and “strong” forms. The Weak Anthropic Principle (WAP) simply states that we observers can only find ourselves in a universe capable of supporting observers. In other words, there’s an observational selection effect: no one should be shocked that the universe has the conditions for their existence, because if it didn’t, they wouldn’t be here to notice! As astrophysicist Luke Barnes explains, “if physical life-forms exist, they must observe that they are in a universe capable of sustaining their existence.”

This principle, by itself, is a logical truism; it doesn’t explain why a life-permitting universe exists, but it cautions us that any conscious beings will inevitably observe fine-tuning. The Strong Anthropic Principle, in some interpretations, goes further – suggesting that it might be inevitable or necessary for the universe to evolve observers (or that multiple universes exist, and we are in one of the rare habitable ones).

Philosophers debate whether the anthropic principle diminishes the force of the design argument. If there were many tries (many universes with varying constants), then observers would naturally exist in the few universes that “got it right” by chance – anthropic selection would guarantee that any beings find their universe fine-tuned, no miracles needed. However, if there is only one universe, the anthropic principle alone doesn’t solve the improbability; it just restates that we won the cosmic lottery, otherwise we wouldn’t know about it. The teleological argument’s advocates often use analogies to illustrate this: Suppose you face an execution by a 50-member firing squad and all shooters miss. You shouldn’t simply shrug and say “well, if they hadn’t missed I wouldn’t be here to notice” – you would reasonably suspect something intervened (perhaps they intended to miss). Likewise, simply noting that we observe a hospitable universe because we couldn’t observe a hostile one does not fully answer why this universe, against all odds, has the right properties to allow life.

Necessity vs. Chance vs. Design: Philosophically, we can categorize explanations of fine-tuning into three broad camps. (1) Physical necessity – perhaps there is some underlying law or Theory of Everything that forces the constants to have the values they do, with no freedom. If that were true, then there is no accident or choice: a life-permitting universe might be the only possible universe. However, current science has found no evidence that constants must be exactly as they are; on the contrary, our best theories treat them as free parameters. It would be a stunning coincidence if the only theoretically possible values just happened to also be the tiny range that supports life. Thus, most experts doubt pure necessity accounts for fine-tuning (unless one invokes a Creator who built necessity into nature, which circles back to design). (2) Chance – in a single-universe context, this means we simply got very, very lucky. The odds against all parameters falling in the life-friendly zone are enormous, but chance by itself cannot be ruled out logically. Some philosophers argue that using probability for unique cosmological events is tricky – we have a sample size of one universe, and perhaps we lack information to say how probable different constants really are. Nevertheless, given the extreme improbabilities cited (like Penrose’s 1 in 10^10^123 for one condition), relying on chance alone strikes many as a less plausible stance. This pushes consideration to a modified chance hypothesis: (3) A multiverse (discussed more in the next section), where myriad universes exist with different parameters, and by chance one of them turned out like ours. In a multiverse, it’s not surprising that some universe is hospitable – we just happen to live in that fortunate bubble. Finally, (4) Design – the idea that an intelligent Agent (God) chose the constants deliberately. Design is not a scientifically testable hypothesis, but proponents argue it is a rational inference to the best explanation: a cosmic mind has a motive (produce life) and the ability to set the laws of physics, thus expecting life-favorable constants is reasonable if such a mind exists. By contrast, on atheistic chance alone, there’s no reason to expect any life at all – making our existence a profound surprise. This inferential reasoning is at the heart of the fine-tuning argument for God’s existence.

Different philosophers assign different weights to these options. Those inclined toward theism find the design inference compelling and see fine-tuning as a powerful clue that physical reality is not random but intentional. Non-theists often prefer the multiverse or unknown physical principles as alternatives that don’t invoke supernatural design. Some, like philosopher of science Elliott Sober, caution that we should be careful with selection effects and not jump to conclusions about probability without more data (pointing out that we might only be aware of universes where observation is possible). Others, like Victor Stenger, have attempted to refute fine-tuning by arguing that a range of different physical constants might still allow some form of life or complexity – claiming the case for fine-tuning is overstated or a “fallacy.” For example, critics note that many fine-tuning arguments varied one constant at a time, holding others fixed, which might exaggerate fragility; perhaps a universe could compensate a change in one constant with a change in another and still produce complexity. While this is a fair caution, detailed studies (including simulations varying multiple parameters) generally still find that truly life-permitting combinations occupy a tiny volume in parameter space. The consensus is that fine-tuning is real – the open question is how to interpret it.

In summary, philosophically the fine-tuning argument uses logical reasoning and probability to argue that cosmic design is more plausible than a fluke. It resonates with the intuitive sense that such a “Goldilocks” universe is too perfect to be a coincidence. At the same time, it raises deep questions about inference: Can we apply probabilistic reasoning to the universe as a whole? Are we biased by the fact of our own existence? These questions show why fine-tuning spans physics and metaphysics – it forces us to consider why reality is the way it is.

Theological Perspectives on Fine-Tuning

The apparent fine-tuning of the cosmos has not gone unnoticed by the world’s religious traditions. For many believers, this scientific discovery is seen as a stunning confirmation of their faith in a purposeful Creator. They interpret the fine-tuning as “the heavens declaring the glory of God” – a modern echo of ancient scripture.

In Judeo-Christian Thought: The Bible contains numerous passages asserting that the universe was deliberately fashioned by God for a purpose. For example, around 700 BCE the prophet Isaiah wrote: “For thus says the LORD, who created the heavens… who formed the earth and made it… He did not create it to be empty, He formed it to be inhabited.”

This idea – that God formed the world specifically as a habitation for life (and ultimately for human beings) – dovetails remarkably with the fine-tuning argument. The Book of Psalms similarly exclaims: “The heavens declare the glory of God; the skies proclaim the work of His hands” (Psalm 19:1). Theologians interpret such verses to mean that the order and suitability in creation are intentional signs of God’s craftsmanship. Christian apologists often point to fine-tuning as scientific evidence of this biblical concept of a designed cosmos. For instance, the Catholic physicist-priest John Polkinghorne refers to fine-tuning as an insight into a divine “purpose-bearing” cosmos, calling them “signposts to God.” Christian writers note that a universe with billions of galaxies and a 14-billion-year history was necessary to produce the heavy elements, stable solar systems, and planetary environments that eventually allow life – exactly what one might expect if God works through natural processes to bring about life. Some also cite the New Testament, where Paul writes that God’s attributes are “clearly seen” in the creation (Romans 1:20), as consistent with fine-tuning: the coherence and intelligibility of the universe reflect a rational Mind behind it. While traditional design arguments focused on biological complexity, fine-tuning shifts the focus to physics and cosmology, but the underlying theological claim is the same: order + purpose = evidence of a Creator.

In Islamic Thought: Islamic theology has long emphasized that Allah created the universe with balance, order, and precise measure. The Quran contains verses that closely parallel the idea of fine-tuning. For example, “Indeed, all things have We created in proportion and measure” (Quran 54:49). Another verse, in Surah Ale Imran, records believers saying, “Our Lord, You have not created this universe without purpose – Glory be to You!”

The verses quoted as epigraph also perfectly resonate with all the philosophical and theological discussion so far.

The Quranic statements align strongly with the fine-tuning argument: the cosmos is not a random accident (batilan, “in vain/aimlessly” as the Quran says), but the deliberate work of an Al-Hakeem (The Wise) Creator who calibrated it for a meaningful end. Contemporary Muslim scholars and apologists often incorporate fine-tuning into their proofs of God’s existence, seeing it as a modern confirmation of what the Quran calls the “signs” of Allah in the heavens and earth. They argue that the delicate laws and constants reflect divine wisdom. Some even consider fine-tuning a scientific miracle hinted at by verses about the ordered heavens. Overall, in Islam, the fine-tuning fits the belief in tawhid – that one God is the ordainer of all natural laws and created everything with qadar (precise planning).

In Other Traditions: Other theistic worldviews likewise see the fine-tuning as supportive of their beliefs. Judaism, sharing the Hebrew scriptures with Christianity, similarly holds that God designed the universe with intention. Jewish theologians might point to the fine-tuning as an aspect of Chokhmah (divine wisdom) in creation. Deists (who believe in a non-interventionist Creator) also find fine-tuning very compatible – the idea of a “Divine Watchmaker” setting up the cosmic machine exactly right is a classic deist image. Even some Hindu thinkers have noted that the concept of Rta (cosmic order) and an intelligent Brahman behind the universe could be seen in the fine-tuning notion, though Hindu cosmology is often cyclic and vast in scope. In Eastern religions that are less theistic (like Buddhism or Taoism), fine-tuning is less directly cited, but the remarkable harmony of the cosmos can still inspire spiritual wonder or ideas of a principle of order (Dharma or Tao) underlying reality. Generally, however, it is the monotheistic faiths that most readily integrate fine-tuning as apologetic support for their doctrine of creation.

Scripture and Science in Dialogue: What is striking is how fine-tuning has opened a dialogue between modern science and ancient theology. Religious interpreters are careful to not overstate the argument – fine-tuning doesn’t “prove” God in a mathematical sense, but it is seen as highly suggestive. It takes a feature of the natural world – objective, quantifiable physics – and finds it resonates with what scriptures have long said: that a rational mind underlies the universe. For believers, fine-tuning thus strengthens the cumulative case for faith, adding a cosmological dimension to existing arguments. It’s often paired with the “Big Bang” theory’s implication of a cosmic beginning (which many see as echoing the idea of a creation event). Indeed, Pope Benedict XVI remarked that the Big Bang and fine-tuning are not contrary to the idea of creation, but “invite us to go beyond” scientific explanations to consider the divine Logos (rational principle) behind them. Religious individuals who are scientists, such as Francis Collins (a geneticist and Christian), also cite fine-tuning as one factor among many that led them to see harmony between science and belief in God.

In summary, theological perspectives across Judaism, Christianity, and Islam largely view the fine-tuning evidence as consistent with and supportive of the belief in a purposeful Creator. They often express that it is thrilling and faith-affirming to see scientific discoveries “catching up” to theological intuitions. Of course, skeptics might respond that this is a biased interpretation, but for people of faith, fine-tuning feels like discovering a message in the fundamental fabric of reality – a message that says “You are not here by accident.”

Counterarguments and Alternative Explanations

While fine-tuning is widely accepted as a scientific observation, its interpretation remains hotly debated. Skeptics and many scientists seek alternative, naturalistic explanations that do not require invoking God. The primary counterarguments include the multiverse hypothesis, anthropic selection effects, and questioning the premise of extreme improbability. Let’s examine these:

The Multiverse Hypothesis: By far the most discussed alternative to cosmic design is the idea that our universe is just one of many universes – perhaps an infinite ensemble of universes, each with randomly set physics constants. If a multiverse exists, then it’s almost inevitable that some universe in the ensemble would have the right conditions for life. We just happen to be in one of the lucky universes (we had to be, or we wouldn’t be here to notice). This scenario can make fine-tuning seem less “special” or surprising without needing a designer. How might a multiverse come about? One proposal is eternal inflation – a cosmological theory in which pocket universes are constantly spawned with varying properties. Another comes from string theory, which suggests a vast landscape of possible vacuum states (perhaps 10^500 or more), each of which could be a universe with different constants. If all those possibilities exist physically, then a life-friendly universe is not a 1 in 10^120 fluke; it’s an expected outcome somewhere in the multiverse.

The multiverse idea is taken seriously in physics, but it remains hypothetical. By definition, other universes (if they exist) are not observable to us, except perhaps indirectly. Critics argue that invoking an infinity of unobservable universes is not a very simple explanation – some say it’s like “multiplying entities” to dodge the fine-tuning problem. Moreover, if the multiverse itself is governed by laws or a process (like inflation) that produces universes, one could still ask: why does that meta-law exist, and does it itself require fine-tuning? (For example, the inflation field’s properties might need to be just right to generate a multiverse of diverse constants.) In reply, multiverse proponents will often appeal again to anthropic reasoning: maybe many different kinds of universes exist, and only in some regions of the multiverse tree can life evolve and ask these questions. This remains an area where physics, metaphysics, and even philosophy of science intersect. Some philosophers argue that the multiverse explanation, while possibly true, lacks empirical testability – making it almost a philosophical explanation rather than a scientific one. There is ongoing debate if there could be any indirect evidence (for instance, maybe adjacent universes could collide and leave an imprint on our cosmic sky – scientists have actually searched for such signs, without conclusive results so far). Until a testable multiverse prediction emerges, design proponents will point out that the multiverse is an imaginative but unproven way to avoid a single, created universe.

Weak vs. Strong Anthropic Principle (Redux): The anthropic principle, as mentioned, is often invoked alongside the multiverse. In a single-universe context, the weak anthropic principle (WAP) simply reminds us that we must observe conditions that allow our existence. This is true but doesn’t explain fine-tuning; it only explains why we shouldn’t be shocked to see a life-permitting universe (because if it weren’t, we wouldn’t be here). Some skeptics argue that this is enough: since we could only observe a fine-tuned universe, it’s a mistake to think that observation needs further explanation – maybe it’s just a “brute fact” that the universe is this way, and only in such a universe can the question arise at all. Proponents of design respond that this is like saying “don’t seek any explanation, it’s just a coincidence we’re allowed to exist.” Most would agree anthropic reasoning alone doesn’t fully satisfy our curiosity; at best, it reframes the problem: Given that we exist, what’s the most plausible explanation that our universe permits life?

The strong anthropic principle (SAP) in one form posits that the universe must produce life or that life is in some sense built into the structure of the cosmos. Some interpretations verge on teleology without a theistic framework (e.g. the idea that consciousness is somehow required in the universe, or that perhaps many universes exist but only those with observers are “realized”). These ideas are speculative and not mainstream, but they show the range of thought in trying to explain why the universe seems almost as if it “knew we were coming.” The SAP is controversial because taken naively it can sound tautological or mystical. In practice, when scientists talk about anthropic explanations today, they usually mean a combination of WAP + multiverse: i.e., many universes exist, and of course we find ourselves in one of the rare habitable ones.

Other Naturalistic Explanations: Beyond the multiverse, is it possible that future physics will remove the need for fine-tuning by showing the constants couldn’t have been otherwise? Some researchers hold out hope for a final Theory of Everything that yields only one self-consistent set of laws – which happens to be our set. If such a theory is found, it might turn “contingent” properties into logically necessary ones. However, even if that occurs, one might still ask: why that theory (and set of laws) and not another? Interestingly, even a unique Theory of Everything would not explain why its structure leads to life-compatible conditions – it would just say “these are the only conditions possible.” If those unique conditions permit life, we’re still confronted with the question of purpose versus coincidence (some would say a life-permitting TOE would itself smell of design). On the other hand, if the unique theory didn’t allow life, we wouldn’t be here – so it’s somewhat circular. At present, this is speculative since no such final theory exists.

Another angle: some scientists have explored whether different kinds of life might exist under alternative constants. If the fine-tuning argument only considered life “as we know it” (carbon-based, water-dependent, etc.), could radically different physics still produce some form of complexity or information processing that counts as life? For instance, maybe if electromagnetism were weaker, you couldn’t have atoms, but perhaps stable “molecules” of particles bound by gravity could form creatures (though gravity is so much weaker that this seems implausible on small scales). Or maybe if the strong force were a bit different, you get a universe with chemistry based on different elements or nuclear compounds. So far, studies suggest that the basic requirements for any complex order (stable bound structures, energy sources like stars, a variety of elements to enable complexity) rule out most variations – it’s not just carbon life that’s threatened, but any form of organized complexity. Nonetheless, this consideration adds a note of caution: we know one type of life – our kind – can arise in this universe. We don’t have exhaustive knowledge of all conceivable life in all conceivable universes to be absolutely certain nothing could exist in a slightly different cosmos. However, given how hostile most variants appear, it’s reasonable to say our universe is uniquely congenial to any life whatsoever so far as we understand.

Objections from Atheism and Skepticism: Atheists typically argue that invoking God to explain fine-tuning might be premature or unnecessary. They sometimes accuse the design argument of being a “God of the gaps” – inserting God to explain what science currently can’t. If one is confident that science will eventually find a natural explanation (like a multiverse or deeper laws), then positing God now is seen as unwarranted. Moreover, skeptics like Sean Carroll and others have noted that if God’s purpose was to create life, the universe is an awfully roundabout way to do it – with vast uninhabitable expanses, and eons of time where no life existed until very recently on one tiny planet. In other words, they question, if the universe is fine-tuned for life, why is life so exceedingly rare and fragile in it? Defenders reply that the universe’s immense scale and age are a necessary backdrop for even one planet of life (since it took billions of years of cosmic evolution to brew heavy elements and assemble them into Earth). Another common rebuttal is the “who designed the Designer?” retort – though strictly speaking this is beyond the fine-tuning argument’s scope (the argument infers design as the best explanation for the universe’s order; it doesn’t claim to explain the origin of the Designer – that goes into deeper philosophical theology about God as uncaused or eternal).

Some skeptics maintain that fine-tuning isn’t as statistically impressive as often claimed. They highlight that we don’t actually have a probability distribution for constants; phrases like “one in a million” or “one in 10^120” might not be rigorous if we don’t know the space of possibilities. While true, the argument can be reframed in terms of likelihood: “If no God, what is the chance of a life-permitting universe? If God, what is the chance?” Even if those probabilities aren’t numerically precise, one can qualitatively reason that the chance of a universe being life-friendly by accident is extremely small, whereas if a powerful God wants life, the chance is appreciably higher (not certain, but presumably high). By Bayesian logic, this makes a fine-tuned universe evidence favoring God. Critics might dispute the assignments of those probabilities, but that is where much philosophical exchange occurs.

Finally, some physicists question if we’re truly looking at all possibilities. Sabine Hossenfelder, for example, has argued that fine-tuning claims often fix other features of physics and only vary a couple of constants, which might mislead us. Perhaps changing initial conditions alongside constants, or allowing new physics to come into play, could allow life in scenarios we haven’t imagined. This is a fair point: our conclusion that “life couldn’t exist” is only as good as our understanding of what life requires. However, given our best current knowledge, most alternative scenarios either collapse into trivial uniformity (no complexity) or remain as diffuse chaos (no structure), reinforcing that something special is going on in our universe.

In summary, the multiverse hypothesis stands as the most robust secular explanation for fine-tuning, essentially by rendering the lucky draw not so implausible across many tries. It shifts the question from “why this universe?” to “why this multiverse?” – a question some argue is beyond science. The anthropic principle provides a context for understanding why we shouldn’t be surprised to observe fine-tuning, but by itself it doesn’t resolve the mystery of how such a life-friendly setup came to be. Other naturalistic angles either appeal to future knowledge or critique the inference methods of theists. All these counterarguments ensure that the fine-tuning debate remains vibrant. Both sides – theistic and atheistic – acknowledge the facts of fine-tuning; they diverge on philosophical interpretation. As cosmologist Bernard Carr said, “If you don’t want God, you’d better have a multiverse.” In other words, absent a multiverse, the fine-tuning cries out for explanation, and many see design as the most straightforward answer.

A Balanced Conclusion

The fine-tuning of the universe is a fascinating crossroads of science, philosophy, and theology. On the one hand, it presents a strong intuitive argument for the existence of a cosmic Designer: the universe looks “rigged” in our favor, and it’s hard to imagine that sheer chance, out of all possible universes, hit upon one so compatible with life. The argument’s strength lies in clear scientific findings (the sensitivity of physical structures to fundamental parameters) and in the relative paucity of explanations other than design or multiverse. It has broad appeal because it uses empirical facts and simple reasoning – you don’t need advanced theology to feel the weight of the question, “Why do the laws of nature allow us to exist?”

The multiverse theory, while currently speculative, could potentially make fine-tuning a non-issue (though one might then debate whether the multiverse itself shows evidence of design). Additionally, critics point out that even if fine-tuning suggests some intelligent cause, it doesn’t by itself tell us much about the nature of that cause. Is it the God of classical theism, a deistic creator, a simulator in a higher reality, or something else? The fine-tuning argument typically assumes a God with the intent to produce life, which fits well with the God of Abrahamic faiths, but strictly speaking, fine-tuning could only establish a generic intelligence behind the universe’s order.

Multiverse seems to be a useful term to allow those who are not ready for belief in God to deny it, but ultimately it will need explanation as well. At the end of the day we need an explanation for our universe that is not contingent but is necessary. The only reality that can fulfil the definition of necessary in my mind is God.

Nevertheless, the debate over fine-tuning has had a fruitful impact on broader discussions. In science, it has motivated new lines of inquiry (like multiverse research, inflation theory, and even alternative physics scenarios). It forces scientists to confront foundational questions: Why these laws? which historically were often shrugged off as “just given.” In philosophy, fine-tuning has reinvigorated age-old arguments about probability, inference, and the principle of sufficient reason (the idea that every fact needs an explanation). Philosophers have published extensive analyses on whether fine-tuning is evidence of design or simply a selection effect. In theology, fine-tuning has become part of the dialogue between faith and reason – it’s cited in apologetics, but also prompts deeper theological reflection on how God might set up a universe that develops life through natural processes.

Ultimately, whether fine-tuning convinces someone of God’s existence often depends on their prior commitments and how they weigh the plausibility of alternatives. Believers see it as a powerful alignment of scientific discovery with their belief in a deliberate Creator – a pointer toward the truth of a cosmos created with intention. Non-believers may acknowledge the enigma but reserve judgment, preferring to await a possible physical explanation or accepting that we just happen to be the lucky winners in a vast cosmic lottery.

What everyone can agree on is that fine-tuning is a remarkable feature of our universe. It evokes a sense of wonder that the deepest laws of physics are intertwined with the emergence of life and consciousness. As Stephen Hawking noted, it “seems remarkable that the universe is so finely tuned” for our existence – whether one attributes that to God or to a multiverse, it is a fact that invites awe. In a way, fine-tuning brings us back to very basic, child-like questions: “Why are we here? Why is there something rather than nothing – something so hospitable to us?” Those questions straddle the empirical and the existential. The fine-tuning argument for God doesn’t force an answer, but it certainly enriches the question. It has made the cosmos a central piece of evidence in the discussion of divine existence, putting scientific discovery in dialogue with humanity’s oldest philosophical and theological ideas. And regardless of where one stands, that intersection – of cosmology and meaning – is a profound place to be. The conversation is far from over, but it reminds us that the universe we live in is a truly extraordinary place, perhaps pointing beyond itself to something (or Someone) even greater.

Sources:

- Barnes, L. & Lewis, G. A Fortunate Universe: Life in a Finely Tuned Cosmos. Cambridge University Press, 2016 – discussions on small changes to constants and habitability phys.orgphys.org.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy – “Fine-Tuning” entry: detailed survey of fine-tuning cases in physics plato.stanford.edu and philosophical interpretations.

- Rees, M. Just Six Numbers: The Deep Forces That Shape the Universe. Basic Books, 2000 – explains six key constants (N, ε, Ω, λ, Q, D) that underpin cosmic structure en.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org.

- Templeton Foundation, “What is Fine Tuning?” (Oct 25, 2022) – overview of fine-tuning with firing squad analogy and explanation of multiverse and anthropic principle templeton.orgtempleton.org.

- Phys.org – “Is the universe fine-tuned for life?” (Nov 3, 2021) – reports Luke Barnes’ work and distinctions between fine-tuning and anthropic principle phys.orgphys.org.

- Hoyle, F. (1950s) – on carbon resonance enabling life: “A common sense interpretation of the facts suggests that a superintellect has monkeyed with physics…” mindmatters.ai, quoted in various sources.

- Holy Bible, Isaiah 45:18 – “[God] did not create [the earth] to be empty, He formed it to be inhabited” biblehub.com, affirming a purposeful creation.

- Holy Quran 54:49 – “Verily, all things have We created in proportion and measure” corpus.quran.com; Quran 3:191 – “You did not create this without purpose, glory to You!” surahquran.com – theological parallels to fine-tuning.

- Carr, B. & Rees, M. “The Anthropic Principle and the Structure of the Physical World.” Nature 278, 605 (1979) en.wikipedia.org – early paper noting that “it would still be remarkable” that the laws of nature coincidentally permit life.

- Stenger, V. The Fallacy of Fine-Tuning (Prometheus, 2011) – presents counterarguments suggesting life might be possible under other constants and criticizing the design inference.

- Hossenfelder, S. (2016), Backreaction blog – argues that typical fine-tuning arguments explore only a tiny part of parameter space and don’t consider multi-parameter variations futureandcosmos.blogspot.com.

- Hawking, S. A Brief History of Time (Bantam, 1988) – discusses the sensitivity of early universe conditions (expansion rate, etc.) and raises the question of why conditions are so exactly set for life (though Hawking himself leaned toward scientific explanations over divine ones).

These sources (and many others) provide a wealth of information on both the scientific details of fine-tuning and the diverse perspectives on what it means. The fine-tuning argument continues to be refined as our understanding of the universe grows. Whether one ultimately sees the fine-tuning of the cosmos as pointing to God, a multiverse, or something unknown, it remains one of the most intriguing discussions at the boundary of science and deeper human inquiry. The universe, against all odds, works for us – and that is a fact that invites thoughtful reflection, no matter one’s worldview.

Leave a comment