Written and collected by Zia H Shah MD, Chief Editor of the Muslim Times

Introduction

Ismaili Shi‘ism is a branch of Shia Islam known for its emphasis on the esoteric interpretation of the faith and the centrality of the Imam (spiritual leader) in guiding the community. Originating in the 8th–9th centuries, the Ismaili tradition developed a distinctive theology that integrates core Islamic principles—such as the oneness of God and the mission of Prophet Muhammad—with a unique philosophical outlook. Historically, Ismailis established the Fatimid Caliphate and produced an extensive intellectual heritage, and today they continue as a vibrant community under the guidance of the Aga Khan (the present Imam). This analysis explores Ismaili theology and philosophy, how it diverges from Twelver Shi‘ism and Sunni Islam, the role of reason and ta’wil (esoteric exegesis), the evolution of various Ismaili branches, and the ethics and communal life shaped by Ismaili ideals.

Core Theological Principles of Ismaili Shi‘ism

Ismaili theology shares the fundamental pillars of Shi‘a Islam but reinterprets them in an esoteric and philosophical light. Classical Ismaili teachings articulate a holistic view of God, prophecy, Imamate, justice, and the end of times, integrating Islamic tenets with Neoplatonic thought. The following are the core theological principles as understood in Ismaili Shi‘ism:

- Tawḥīd (Divine Oneness and Transcendence): Ismailis uphold the absolute oneness and transcendence of God as the bedrock of their faith. In Ismaili metaphysics, God is the unknowable and indescribable One, exalted beyond all human attributes and understandingamaana.org. This radical monotheism is expressed via tanzīh (divine incomparability) – God cannot be limited by names or qualities. Ismaili thinkers, such as Abu Ya‘qub al-Sijistānī, carried the concept of tawḥīd to its furthest logical extent through a “via negativa,” even surpassing the anti-anthropomorphic stance of the Mu‘tazilitesamaana.org. God is seen as beyond being and non-being, and the first emanation of creation is the Universal Intellect (‘aql al-kull), brought forth by God’s command (amr) rather than by any diminution of the divine essenceamaana.orgamaana.org. This philosophical theology reinforces the Quranic principle of divine unity by ensuring no plurality or human-like attribute is ascribed to the Creator. For Ismailis, Tawḥīd is not only a doctrine about God’s nature but also an ethical imperative: it demands that believers devote themselves to the one God alone and seek to reflect divine attributes such as justice and mercy in the world, while recognizing that God in Himself remains beyond all conception.

- Prophecy (Nubuwwa) and Revelation: Like all Muslims, Ismailis believe Prophet Muhammad is the final Messenger of God and the Seal of Prophets (Khātam al-Anbiyā’)en.wikipedia.org. They affirm that divine revelation (waḥy) culminated in the Quran, which contains an outer meaning for all believers and a hidden meaning for those with deeper insightbritannica.com. In Ismaili thought, prophets (nāṭiqs, “Enunciators”) have appeared in sacred history to found religious communities and bring scripturesamaana.org. Ismaili tradition sometimes describes a typology of cycles of prophecy: human history is divided into eras initiated by great prophets – Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, Jesus, and Muhammad – each of whom proclaimed a religious law (sharī‘a) for their communityamaana.org. Muhammad, as the final Prophet, brought the definitive revelation for humanity and a universal message. However, the role of prophecy in Ismailism is intertwined with the Imamate: prophets provided the exoteric (ẓāhir) form of religion, while designating successors to continue guiding the community in the esoteric (bāṭin) truthsamaana.org. Thus, Ismailis revere all earlier prophets and especially Muhammad, seeing his message as containing layered meanings that the Imam can progressively unveil. The closure of prophethood in no way diminishes the need for ongoing divine guidance; rather, it passes the mantle from nubuwwa to walāya (guardianship), vested in the Imams.

- Imamate (Leadership of the Imams): The Imamate is the cornerstone of Ismaili theology and community. Ismailis, as Shi‘a, believe that after Prophet Muhammad, spiritual authority was entrusted to the Prophet’s family (Ahl al-Bayt), specifically to Imam ‘Ali and his descendants. The Ismaili Imams are regarded as the rightful successors of the Prophet in both spiritual and temporal matters. Ismaili doctrine stresses the permanent need of humankind for a divinely guided, infallible leader (imam) to teach and govern with justiceamaana.org. In Ismailism, the Imam of the Time is seen as the living embodiment of the Quran’s wisdom and the locus of divine guidance on earthen.wikipedia.org. Each Imam inherits the nūr (light) of the Imamate, a spiritual charisma traced back to ‘Ali. Early Ismaili theologians developed a sophisticated understanding of the prophetic chain (silsilat al-nubuwwa) in which the Imamate is a continuation of prophetic guidance: every major prophet (nāṭiq) had a legatee (waṣī or sāmit) who initiates the inner teachings, followed by a line of Imams who guard and interpret the true meaning of the revelationamaana.org. The cycle culminates in a Mahdi or Qā’im – an eschatological figure from the line of the Imams. While Twelver Shi‘ism holds that the 12th Imam is the Mahdi in occultation, Ismailis believe the Imamate continues in a living line to this day. The Ismaili Imam is not only the community’s spiritual guide but also the interpreter of scripture and law, with the authority (by divine designation, naṣṣ) to define the faith’s practice for Ismailis in different timesen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. Loyalty (walāya) to the Imam is, for Ismailis, a key religious obligation, as the Imam is viewed as the guide and intermediary through whom believers attain deeper understanding of God’s message. This strong emphasis on the Imamate profoundly shapes Ismaili identity, distinguishing it from other Muslim traditions.

- Divine Justice (‘Adl): Like other Shi‘i schools, Ismailism upholds ‘adl (justice) as a fundamental divine principle. In line with Shi‘a and Mu‘tazilite theological heritage, Ismailis assert that God is just and cannot commit injustice; God orders the good and shuns evil, and He does not wrong His creatures. This belief in divine justice carries implications about human free will and moral responsibility: evil and suffering are not capriciously willed by God but often result from human actions and the misapplication of free will. Ismaili theology teaches that God, though absolutely transcendent, acts with purpose and wisdom, and all of creation is endowed with an underlying order and fairness. The appointment of prophets and Imams itself is seen as a mercy and justice from God – providing humanity with guidance so that people are not left to stray without directionamaana.org. Whereas Sunni Ash‘arite theology tended to say that whatever God does is just by definition, Shi‘i theologians (including Ismailis) maintained that God’s justice is an objective reality discernible by human reason – for example, God would not impose obligations beyond a person’s capacity or punish without providing guidance. The Ismaili vision of a just God also translates into the goal of a just society: as the influential Ismaili philosopher Nāṣir-i Khusraw wrote, prophets and Imams collectively aim to establish justice on earth and restore the harmony intended in creationiep.utm.edu. Thus, ethical conduct and social justice are inseparable from theology – to know God’s will is to strive for equity, compassion, and righteousness in individual and communal life. While Ismaili texts may not always treat ‘adl as a standalone doctrine (as Twelver Shi‘ism does), they inherently affirm it by emphasizing God’s wisdom (ḥikma) and purpose in all things, and by insisting on the moral responsibility of the faithful to uphold justice, guided by the Imam’s teaching.

- Eschatology (Resurrection and the End of Time): Beliefs about the end of time (ākhir al-zamān) and the hereafter (ākhira) in Ismailism combine Quranic teachings with symbolic interpretation. Ismailis affirm the general Islamic teaching of resurrection and final judgment (Qiyāma) but often with an esoteric twist. In Ismaili eschatology, history is seen as progressive and cyclical, moving toward the full revelation of divine truthamaana.orgamaana.org. Each prophetic era ends with the advent of a Qā’im (Mahdi) from the Imam’s lineage, who initiates a period called the “Great Resurrection” (qiyāmat al-qiyāmāt). During this final era, according to classical Ismaili doctrine, the hidden meanings of all revelations will be unveiled openly and completely to humanityamaana.org. The Ismaili Fatimid tradition taught that the seventh and final era (initiated by the Qā’im) would not bring a new law but would abrogate the exoteric Sharī‘a, as the enlightened believers would then be governed by pure spiritual knowledgeamaana.org. In other words, the rituals and legal practices (which belong to the ẓāhir) would give way to the ḥaqā’iq (eternal truths) previously known only to the initiated elite. An example of this belief in practice occurred in 1164 at the Nizari Ismaili fortress of Alamut, when Ḥasan ‘Alā Dhikrihi’l-Salām declared the beginning of a symbolic “Resurrection” – a moment when the veil of formal religion was lifted for the Ismaili faithful, emphasizing the inner meaning as their true salvation. Alongside such spiritualized interpretations, Ismailis also share the common Islamic hope in personal life after death: the soul’s progress continues beyond this world, attaining paradise (jannah) or distance from God (hell) based on one’s enlightenment and obedience to God. However, Ismaili teachings often describe paradise and hell in intellectual and spiritual terms – paradise being the joy of the soul in attaining true knowledge (ma‘rifa) of God, and hell the deprivation of that knowledge. Contemporary Nizari Ismailis, guided by the living Imam, tend to focus less on apocalyptic timetables and more on the idea of an ongoing, present fulfillment of religion’s purpose. The present Imam is sometimes described as performing the role of qa’im in every age by making esoteric insights accessible to the believers. Thus, eschatology in Ismailism is not merely about end-time events – it is also about the soul’s journey to enlightenment and the eventual triumph of the truth. It serves as a horizon of hope that history will culminate in the vindication of the righteous and the full realization of God’s justice and unity, as well as a present reality in which the Imam’s guidance leads the believer from the worldly to the eternal.

Differences from Twelver Shi‘ism and Sunni Islam

Ismaili Shi‘ism diverges in important ways from the other major Islamic traditions, namely Twelver (Imami) Shi‘ism and mainstream Sunni Islam. These differences encompass leadership and authority, interpretations of law and ritual, and theological emphases:

Differences from Twelver Shi‘a Islam

Ismailis and Twelver Shi‘ites share belief in ‘Ali and the early Imams, but they split over the succession of the Imamate in the 8th century. Twelvers recognize a line of Twelve Imams ending with Muhammad al-Mahdi (the 12th Imam) who is in occultation, whereas Ismailis uphold a continuing line of Imams through Ismā‘il ibn Ja‘far (the son of the 6th Imam) and his descendants. After Imam Ja‘far al-Ṣādiq’s death (765 CE), Twelvers followed his younger son Mūsā al-Kāẓim, but Ismailis followed his elder son Ismā‘il (or Ismā‘il’s son) as the rightful Imam. This led to a permanent split: authority in Ismailism rests with a present, living Imam, whereas Twelvers have no present Imam (awaiting the Mahdi’s return) and delegate religious authority to scholars (mujtahids). The role and definition of the Imam thus differs: Twelvers see the Imam primarily as a past figure (except the Hidden Imam who will return), while Ismailis see the Imam as a current guide who is the “Imam of the Time,” an embodiment of divine guidance in the here and now. Both sects view their Imams as infallible and divinely appointed, but Ismailis invest far more ongoing teaching authority in the Imam’s person, including the flexibility to adapt practice through his ta‘līm (authoritative instruction).

Another key difference lies in esoteric vs. exoteric emphasis. Twelver Shi‘ism certainly has an esoteric dimension (Irfan and mystical philosophy developed by scholars like Ibn ‘Arabi and Mulla Ṣadrā influenced Twelver thought), but over time Twelvers placed greater emphasis on the outward law and the preserved teachings of the Imams through hadith. Ismailism, by contrast, became known for its strong bāṭini orientation – seeking hidden meanings in scripture and rituals accessible only via the Imam’s guidance. For example, in classical Ismaili communities, religious education was structured in graded levels of initiation: believers were gradually taught deeper interpretations of Quranic teachings by the Imam’s missionaries (dā‘is), whereas Twelvers generally taught a more uniform doctrine to all followers. Twelvers and Ismailis also differ on the immutability of the Sharī‘a. Twelver authorities maintain that the religious law brought by Prophet Muhammad can never be superseded or suspended until the end of time (the awaited Mahdi will enforce the same Sharī‘a, not abrogate it). Ismaili doctrine, however, allowed for the idea that exoteric practices might be abrogated or transcended in certain eras – most dramatically, the Nizārī Ismailis at Alamūt believed that the declaration of Qiyāma (Resurrection) by their Imam meant outward ritual obligations were lifted in favor of a purely spiritual focus. Twelver polemicists historically criticized Ismailis for this, accusing them of forsaking the Sharī‘a. In practice, modern Ismailis do still follow core Islamic practices (prayer, fasting, charity), but under the Imam’s guidance they sometimes interpret these in a distinctive way (for instance, substituting specific Ismaili liturgies for the standard forms of prayer). Twelvers, on the other hand, adhere to the Ja‘fari legal school’s prescriptions very closely, paralleling Sunni practice with minor variations.

Theological nuances also differ. Both Twelvers and Ismailis uphold God’s unity and justice and the need for divinely guided leaders, but Ismaili theology was more thoroughly influenced by Neoplatonism and philosophical concepts. Ismaili authors in the Fatimid period described creation in terms of emanations (Intellect and Soul) and saw the Imam as the earthly counterpart of the Universal Intellect. Twelver theology, while not inimical to philosophy, developed its metaphysics more cautiously through scholars like al-Ṭūsī and later the school of Isfahan, always ensuring it aligned with the Quran and hadith as understood by the Twelve Imams. Another point is that Twelvers emphasize that Muhammad was the final prophet and legislator, with no new scripture or law to come, whereas Ismailis, through their doctrine of cyclical eras, at times appeared to expect new revelations (the word “prophet” in Ismaili context can refer to the founding figures of prior eras) – although Ismailis do affirm Muhammad as the final law-bearing Prophet. In sum, Twelver and Ismaili Shi‘ism diverge in the lineage of authority and in how religious knowledge is accessed: Twelvers look back to the texts left by the Imams (with clerical interpreters in the Imam’s absence), while Ismailis look to a living Imam to continuously reveal the faith’s inner truths. Despite these differences, it should be noted that both traditions share love for the Prophet’s family and many aspects of Shi‘i piety (for example, devotion to Imam ‘Alī and commemorations of Imam Ḥusayn’s martyrdom – though Nizārī Ismailis observe ʿĀshūrā’ more privately and with less overt mourning than Twelvers). In modern times, there is greater mutual respect and dialogue, with both communities considered part of the broader Shi‘a and Muslim fraternity.

Differences from Mainstream Sunni Islam

The gap between Ismaili Shi‘ism and Sunni Islam is wider, given both the Shi‘i/Sunni split over succession and the Ismaili penchant for esoteric theology. The primary historical difference is loyalty to the Prophet’s family versus the Caliphate: Sunnis hold that leadership of the ummah passed to elected or selected caliphs (Abū Bakr, ‘Umar, ‘Uthmān, then ‘Alī, followed by the Umayyad, Abbāsid, etc., caliphal dynasties), whereas Ismailis (like other Shi‘a) reject the legitimacy of Sunnī caliphs after Muhammad, except for ‘Alī, and instead follow the line of Imams descended from ‘Alī and Fāṭima. This meant Ismailis developed in opposition to the Sunni political-religious order, at times establishing a rival caliphate (the Fatimids) claiming authority over all Muslims. Beyond political authority, several theological and jurisprudential differences are notable:

- Concept of Religious Authority: Sunnis base religious authority on the Quran and the Sunnah (the example and sayings of Prophet Muhammad) as transmitted by the Sahāba (Companions) and codified by scholars. There is no institution in Sunnism analogous to the Shi‘i Imam. In contrast, Ismailis (and Shi‘a generally) believe the Prophet appointed ‘Alī as successor, and thus religious authority is continued through the Imams. The Ismaili Imam has the authority to interpret scripture infallibly and even to clarify or override previous interpretations. From a Sunni viewpoint, this idea is foreign if not heretical – Sunnis regard the age of revelation and authorized interpretation as closed with the Prophet and the earliest generations. Sunnis also traditionally have been wary of esoteric interpretations that depart from the apparent meaning of the Quran and Hadith. Ismailis, however, see the Imam as the guarantor that deeper meanings (bāṭin) are authentic and not whimsicalbritannica.com. This leads to differing attitudes toward religious texts: Sunnis emphasize strict adherence to the literal word of Quran and Prophetic hadith, whereas Ismailis give primacy to the Imam’s teaching, which may unveil allegorical meanings and adapt certain practices.

- Law and Ritual Practice: Mainstream Sunnis follow one of several law schools (Hanafi, Shafi‘i, Maliki, Hanbali), all of which share the view that the five pillars of Islam (the shahāda, canonical prayers, fasting in Ramaḍān, pilgrimage, zakāt) are unalterable obligations. Ismailis affirm these pillars but sometimes with modified forms. For example, Sunni Muslims pray five times a day in a prescribed manner; Nizārī Ismailis, under guidance of their Imams, pray the devotional du‘ā three times a day instead, and this prayer includes Quranic verses and prayers to God but is distinct from the standard Sunni/Namāz format en.wikipedia.org. Likewise, while Sunnis (and Twelver Shi‘a) fast from dawn to sunset for 30 days in Ramaḍān, Nizārī Ismailis today often emphasize the “metaphorical” meaning of fasting – interpreting it as abstaining from ego and worldly vices – and many do not observe the full conventional fast, or do so only partially en.wikipedia.org. (Musta‘li Ismailis, like the Bohras, however, do fast in Ramaḍān in alignment with broader Muslim practice, illustrating diversity within Ismailism.) In terms of charity, Sunnis give zakāt (usually 2.5% of certain assets to the needy), while Ismailis also give dasond or ʿushr – a tithe to the Imam – which is used for communal welfare and development projects en.wikipedia.org. These practical differences underscore how the Imam’s authority can adjust ritual practice for Ismailis, whereas Sunni practices are standardized based on the Prophet’s example as interpreted by early scholars.

- Theological Outlook: Sunni Islam’s theology is typically based on either Ash‘arite or Māturīdi doctrines, which, unlike Ismaili theology, reject the need for a present Imam or any secret scriptures. Ash‘arite Sunnis emphasize God’s omnipotence (even at the expense of a strict concept of justice) and often prefer bi-lā kayf (accepting scriptural descriptions of God “without asking how”) over philosophical speculation. Ismaili theologians, on the other hand, delved deeply into philosophy and metaphysics, producing elaborate systems describing how God’s command emanated the intellect and soul, and how the Imam and the Prophet fit into the cosmic orderamaana.org. Such discourse was generally beyond the scope of Sunni ulama, who at times even condemned it. Sufi mystics in Sunni Islam did pursue esoteric interpretations and philosophical ideas, but they did so as individuals or orders separate from the Sunni orthodoxy, whereas in Ismailism esoteric philosophy was part of the authorized doctrine of the community. Moreover, Sunnis do not accept the notion of an occult or hidden truth accessible only by initiation – they hold that zāhir and bāṭin must ultimately coincide in the Prophet’s openly taught message. Ismailis maintain that every revelation has both an external and internal aspect, with the internal revealed progressively by the Imamsbritannica.com. This fundamental difference in epistemology (how one knows religious truth) marks Ismailism as distinct from Sunnism.

- Acceptance within Islam: For centuries, many Sunni regimes and scholars viewed Ismailis with suspicion or even as heretical, due to these differences. The Ismaili penchant for secrecy (taqiyya) when persecuted, and the startling actions of groups like the Assassins (medieval Nizārī militants), fueled Sunni distrust historically. In modern times, however, relations have improved significantly. The Ismaili Imam and community are now generally recognized as a legitimate part of the Muslim ummah. Notably, the Amman Message (2005), which was a declaration by a large number of Sunni and Shi‘i scholars, explicitly acknowledged the Ismaili (Ja‘fari and Zaydi) schools as Muslim. Today, Sunni and Ismaili communities often engage in inter-sectarian dialogue. Nonetheless, from a theological perspective, mainstream Sunnis still do not share the Ismaili view of Imamate and esoteric authority. In essence, Sunni Islam and Ismaili Shi‘ism differ on the source of guidance (Caliph & scripture vs. Imam & ta’wil) and on the balance between the outward form and inward meaning of religion, even as they share the same foundational belief in the Quran, the Prophet Muhammad, and the oneness of God.

The Role of Reason, Philosophy, and Esoteric Interpretation (Ta’wīl)

One of the hallmarks of Ismaili Islam is its bold engagement with reason and philosophy alongside revelation. Ismaili thought has often been described as Islamic Neoplatonism due to the early Ismaili adoption of Platonic and Aristotelian ideas filtered through late antique Neoplatonism. However, the Ismailis did not simply borrow Greek philosophy; they Islamicized it into a unique theological framework that served their religious vision. At the same time, Ismailism is a tradition of ta’wīl – interpretive “unveiling” of scripture’s inner meanings – which gives it a distinctly mystical and gnostic character. The balance (and tension) between rational philosophy and esoteric mysticism in Ismailism is a rich field of analysis:

Philosophy and Cosmology: In the 10th–11th centuries (especially during the Fatimid Caliphate), Ismaili scholars authored profound philosophical works. Figures such as Abu Ya‘qub al-Sijistānī, Hamīd al-Dīn al-Kirmānī, and later Nāṣir-i Khusraw developed a cosmology where creation is described in hierarchical emanations from God. They taught that God, the ultimate One, brought forth the Universal Intellect (al-‘Aql al-Kull) by a timeless command (kun – “Be”). From the Intellect emanated the Universal Soul (al-Nafs al-Kull) and through Soul, in gradual stages, the material world. This schema was borrowed from Neoplatonism but modified to accord with Islamic doctrine: Ismaili thinkers emphasized that God creates by His will and word (amr) rather than by necessity. They even avoided calling God the “First Cause” in the strict sense, instead saying God is the cause of the First Cause (i.e. cause of the Intellect) to preserve His total transcendence. In this metaphysical framework, the Imam and the Prophet have cosmological roles. For instance, some Ismaili texts equate the Imam with the Universal Intellect or at least see the Imam as the perfect manifest intellect on earth, guiding the Universal Soul (the community of believers). The ḥudūd (spiritual ranks) in Ismaili cosmology include entities like the Enunciator-Prophet (nāṭiq), the Foundation (asās, referring to the Imam or legatee who discloses inner meanings), and their deputies. This marrying of philosophy and religion allowed Ismailis to articulate Tawḥīd in a philosophically rigorous way – by positing an ineffable God above being, they affirmed divine unity more absolutely than even some kalām scholars did. It also provided a grand intellectual architecture in which every level of existence, from the celestial intellects down to the physical world, had its place and purpose. The influence of this Ismaili philosophy extended beyond the Ismaili community; ideas from Ismaili texts found their way into later Sufi and philosophical works in Persia. Notably, the anonymous Epistles of the Brethren of Purity (Rasā’il Ikhwān al-Ṣafā’), an encyclopedic philosophical collection from Basra, are believed by many scholars to have Ismaili authorship or inspiration. These epistles covered mathematics, music, natural sciences, metaphysics, and spiritual allegories, exemplifying the Ismaili ethos of universal knowledge – integrating Hellenistic science and philosophy with Islamic spirituality.

Ta’wīl (Esoteric Interpretation): The philosophical orientation of Ismailism was matched by a commitment to ta’wīl, meaning “to take [something] back to its origin” – essentially, decoding the inner truth behind religious forms. Ismailis hold that every religious scripture, ritual, or law has an esoteric significance. The Quran’s verses might conceal metaphysical truths or predictions only discernible through symbol and allegory. For example, in Ismaili exegesis, the creation story of Adam might be read not merely as history but as an allegory for the emanation of the Intellect and Soul; the prohibition on certain foods might be interpreted as guidance to avoid morally harmful behaviors, and so on. While Sunni and Twelver scholars also sometimes interpret Quranic symbolism, Ismailism institutionalized ta’wīl as a central religious practice. The Imam and his missionaries taught the initiates how to penetrate the bāṭin. There were ranks (such as ḥujja, dā‘ī, rafīq, etc.) through which an Ismaili disciple might ascend, each rank privy to deeper teachings. This systematized ta’wīl gave Ismaili Islam a mystical character: the faith was not just about obeying laws but about unveiling hidden wisdom leading to enlightenment (ma‘rifa). The ultimate ta’wīl is said to occur in the time of the Qā’im, when all humanity can access the batin without restrictions. Until then, Ismailis believe the Imam of the Time knows the full truth and reveals it gradually according to the capacity of minds and the needs of the time. This approach valorizes an inner, spiritual hermeneutic in parallel to the outer observance of religion. It also encouraged intellectual exploration: even fields like numerology, astrology, and alchemy attracted some Ismaili thinkers, always trying to read the “book of the universe” as well as the scripture for divine signs. Ta’wīl was not arbitrary free-for-all interpretation – it was guided by the lineage of Imams, which ensured to Ismailis that their esoteric readings stayed within the bounds of true Islam. In Ismaili belief, reason and revelation work together in ta’wīl: the Imam’s guidance (rooted in prophetic authority) illuminates the path, and the believer’s intellect is engaged to grasp profound truths.

Rationalism and Mystical Theology: Ismailism’s intellectual tradition is often characterized as a blend of rationality and mysticism. On one hand, the Fatimid-era Ismailis championed the use of human intellect (‘aql) – they argued that ‘aql, being the first creation of God, is the tool by which humans can discern truth and rise above mere literalism. They saw their faith as dīn al-‘aql (the religion of the intellect) in many respects. This rationalism meant that Ismailis were open to debating theologians, engaging with philosophy, and even incorporating scientific knowledge into their worldview. On the other hand, the content which the intellect was used to discover often had a mystical or gnostic flavor – knowledge of the transcendent God, understanding of pre-eternal souls, the destiny of the soul’s reunion with the divine, etc.

The emphasis on inner truth gave Ismaili theology a strong spiritual and ethical orientation: knowing God in Ismailism is not merely knowing doctrines, but undergoing a transformation of the soul (sometimes called the “second creation” of a person). In later centuries, especially after the fall of the Fatimids and during the Nizārī Ismaili dispersal, Ismaili thought continued to evolve. Nizārī Ismailis in Persia (13th–15th centuries) interacted with Sufi orders and adopted more overtly mystical language. The Imams in the Anjudān period (post-Alamūt) often expressed ideas in poetry and symbols reminiscent of Sufism. For instance, the concept of the Imam as a mystical guide who leads the seeker to union with God parallels Sufi ideas of the Murshid or Perfect Man. Yet, even this mystical aspect remained tied to the Imam’s authority rather than an independent Sufi shaykh.

In modern times, Ismaili scholarship (much of it patronized by the Institute of Ismaili Studies in London) has highlighted the community’s intellectual heritage. Ismaili leaders frequently stress that faith and intellect must go hand in hand. The present Aga Khan, for example, has spoken of Islam (and especially Ismaili Islam) as a thinking, spiritual faith that does not shy away from intellectual inquiry and pluralistic dialogue. This continues the tradition whereby Ismailism historically sought to “create a bridge between Hellenic philosophy and religion,” engaging the mind to reach the truths of revelation. The legacy of Ismaili philosophers is increasingly studied and appreciated not only within the community but in broader Islamic philosophy circles as well. In summary, reason and esoteric revelation are seen as complementary in Ismaili thought: philosophy provides conceptual tools to understand the nature of God and the cosmos, while ta’wīl and the Imam’s guidance ensure that this understanding remains rooted in divine revelation and leads the seeker toward spiritual fulfillment, not mere abstract knowledge.

Ismaili Branches: Nizārīs, Musta‘lis, Druze, and Others

Over its 1200-year history, Ismailism has branched into several communities with distinct identities and interpretations, even while sharing a common origin. The major branches include the Nizārī Ismailis (by far the largest group today, led by the Aga Khan), the Musta‘li (mostly known through the Bohras), and offshoots like the Druze. Understanding these branches requires tracing the historical evolution of the Ismaili movement:

- Early Ismailism and the Fatimid Caliphate: The Ismaili movement began in the 8th century as one of several Shi‘a factions that venerated the Imams descended from ‘Alī. Early Ismailism coalesced around the claim that Ismā‘īl ibn Ja‘far was the rightful 7th Imam after his father Ja‘far al-Ṣādiq. Some early Ismailis believed Ismā‘īl did not truly die but went into occultation as the Mahdi britannica.com, while others transferred the Imamate to his son, Muḥammad ibn Ismā‘īl britannica.com. For a few decades, the Ismailis maintained secrecy (partly to avoid Abbasid persecution) and built an underground missionary network (the da‘wa). In the year 899, a pivotal event occurred: an Ismaili leader in Salamiyya (Syria) by the name of ʿAbdullāh (also called Sa‘īd, later Ubayd Allāh) declared himself the Imam and descendant of Muhammad b. Ismā‘īl britannica.com. He would go on to found the Fatimid Caliphate in North Africa, after successfully gaining support and eventually conquering Egypt in 969 CE. The Fatimid Imams – who were simultaneously caliphs – ruled a vast empire (North Africa, Egypt, Syria, and for a time parts of Arabia and the Eastern Mediterranean) for over two centuries amaana.orgamaana.org. Key Fatimid Imams/Caliphs included al-Mahdi (Ubayd Allāh), al-Qā’im, al-Mansūr, al-Mu‘izz (who founded Cairo), al-Ḥākim, and al-Mustanṣir, among others. Under the Fatimids, Ismailism flourished openly: they built institutions like the Dār al-Ḥikma (House of Wisdom) in Cairo, where scholars of various faiths translated works and debated, and they commissioned works on law, theology, and philosophy. This era also saw schisms: the Qarmaṭians in Bahrain and elsewhere were an Ismaili offshoot that broke away from Fatimid allegiance, establishing a republic in eastern Arabia and famously sacking Mecca in 930 CE (stealing the Black Stone) amaana.orgen.wikipedia.org. The Qarmaṭians rejected the Fatimid claim to the Imamate and recognized their own local leaders; they were eventually subdued or faded away by the 11th century, and are generally considered a radical branch that is now extinct en.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. Another offshoot were the Druze, who originate from the time of the Fatimid Imam-Caliph al-Ḥākim bi Amrillāh (d. 1021). Al-Ḥākim’s reign was unusual and led to a posthumous divine veneration: a sect of Ismailis in Syria, inspired by Ismaili missionaries like Ḥamza ibn ‘Alī and al-Darazi, proclaimed al-Ḥākim to be an incarnation of the Divine and the final manifestation of truth. The Druze creed, which soon closed off conversion and became a separate religion, incorporated Gnostic and Neoplatonic ideas and embraced the concept of reincarnation of souls. Although “Ismā‘īlī in origin” britannica.com, the Druze do not follow the Ismaili Imamate anymore and have their own secretive scriptures; today they are a distinct community found mostly in Lebanon, Syria, and Israel, not identifying as Muslims (for the most part). Thus, by the 11th century, the Ismaili movement already had sub-branches and a golden age under the Fatimids.

- Nizārī–Musta‘li Schism (1094 CE): The next major split occurred upon the death of the Fatimid Imam-Caliph al-Mustanṣir bi’Llāh in 1094. There was a dispute over the succession: the established vizier in Cairo supported al-Musta‘li, a younger son of al-Mustanṣir, who became the next caliph-imam. But another faction, including influential Persian Ismaili missionaries, supported the deceased caliph’s elder son Nizār, who was bypassed and later killed. The supporters of Nizār refused to recognize Musta‘li, and thus the Ismaili community split into Nizārīs and Musta‘lis en.wikipedia.org. The Nizārīs eventually centered their movement in Persia, far from the Fatimid court. Ḥasan-e Ṣabbāḥ, a famed Ismaili da‘ī in Iran, seized the mountain fortress of Alamūt in 1090 and made it a base for Nizārī Ismailis. Under Ḥasan and his successors, the Nizārīs created a network of fortresses across Persia and Syria, defying both Sunni Seljuq rulers and the Crusaders. This is the period in which Nizārī Ismailis were often referred to by outsiders as the “Assassins” (from hashīshī – an epithet of unclear origin), due to their use of targeted assassination as a political weapon. The Nizārī Imams during this Alamūt period remained largely in hiding or at least not publicly known, with the community led by “lords” of Alamūt who acted on the Imam’s behalf (some scholars believe the lords themselves were Imams in some cases). A landmark event was in 1164 when the leader Ḥasan II (proclaimed to be the Imam or his representative) declared the Great Resurrection (Qiyāma), as mentioned earlier, signaling a new era of spiritualized religion for Nizārīs. This era ended abruptly in 1256 when the Mongols, led by Hülegü Khan, destroyed Alamūt and most other Nizārī fortresses, killing the Ismaili leadership. Nonetheless, a lineage of Nizārī Imams survived, moving often in secrecy through Persia and Central Asia. By the 14th century, the Nizārī Imams re-established themselves in Anjudān (Persia) and began to reassert communal leadership more publicly. Over time, the center of Nizārī Imamate shifted – during the 19th century the Imams (the Aga Khans) moved to India, and later to Europe. Today, the Nizārī Ismailis are the largest Ismaili branch, led by the 49th Imam, Prince Karim Aga Khan IV en.wikipedia.org. Geographically, Nizārīs are scattered worldwide, with significant populations in South Asia (where they are known as Khojas in some areas), Central Asia (notably Badakhshan in Tajikistan en.wikipedia.org), the Middle East, and East Africa, as well as a growing diaspora in the West. The Nizārīs have evolved a dynamic interpretation of the faith that, while rooted in classical Ismaili principles, is adapted to modern contexts by the guidance of the Imam. They no longer practice political assassination or rebellion; instead, the Nizārī community is known for its emphasis on education, economic development, and philanthropic institutions.

- Musta‘li–Tayyibi Bohras: The Musta‘li branch, which stayed loyal to the Fatimid line in Cairo, had its own schism not long after. The early Musta‘li Imams were Fatimid caliphs in Egypt: al-Musta‘li (r. 1094–1101) and then al-Āmir (r. 1101–1130). When al-Āmir was assassinated, he left no adult heir, only an infant son named al-Ṭayyib. One faction maintained that this child, al-Ṭayyib, was the rightful Imam, though in concealment (and hence the line continued in occultation). The Fatimid regency, however, installed al-Āmir’s cousin as caliph (al-Ḥāfiẓ), thereby creating a rival line. This led to the Ṭayyibi vs Ḥāfiẓi split among Musta‘li Ismailis. The Ḥāfiẓi faction (mostly in Egypt) followed the later Fatimid caliphs, but that line died out after the Fatimid dynasty was abolished in 1171 by Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn (Saladin). The Ṭayyibi Ismailis, on the other hand, went underground, with their Imams remaining in hiding. Leadership of the Ṭayyibi community was entrusted to a rank called Dā‘ī al-Muṭlaq (unrestricted missionary) as the representative of the hidden Imam. Centered in Yemen initially (under the patronage of the Sulayhid dynasty and Queen Arwa al-Sulayhi), the Ṭayyibis later saw their main community shift to Gujarat, India, among merchants who traded with Yemen. These Musta‘li Ismailis in India became known as Bohras (a corruption of vohra, meaning merchant). Over the centuries, the Bohras themselves split into minor sub-sects often due to leadership disputes – the largest today being the Dāwūdī Bohras, alongside smaller groups like the Sulaymānī (mostly in Yemen) and ‘Alawī Bohras. The Dā’udi Bohras, led by a Dā‘ī based in India (Mumbai), claim to follow the Ṭayyibi Imams in concealment and are a Musta‘li Ismaili community. Their practices in many ways resemble Twelver Shi‘a and Sunni practices more than Nizārī practices do: Bohras pray the standard five daily prayers, fast in Ramadan, etc., albeit with certain unique traditions and under their own religious hierarchy. The theology of Musta‘li–Ṭayyibi Ismailis is quite similar to the Fatimid Ismaili doctrine – they emphasize the Imam’s authority (even though he is absent, the Dā‘ī leads in his name) and the importance of ta’wīl. The Bohras, for example, highly regard the same philosophers and poets of Fatimid times and maintain an esoteric tradition. However, living under different historical circumstances (often as a minority under Sunni or Hindu rule in South Asia), the Musta‘li Ismailis became somewhat more externally conservative than Nizārīs – adhering to Islamic law closely and being inwardly orthodox in belief. Today’s Dāwūdī Bohras, under the leadership of the Dā‘ī Mufaddal Saifuddin, number around one million and are known for their tight-knit community and blend of modern business acumen with traditional dress and ritual. They differ from Nizārīs in that they do not have a present Imam to directly interpret religion for them; instead, their Dā‘ī claims authority to guide them based on instructions from the hidden Imam and the precedent of past Fatimid teachings.

- Other Communities and Identities: In addition to these main groups, there are other offshoots and identities within the Ismaili orbit. We have mentioned the Druze, who originated from Ismailism but now are separate. Another community sometimes associated with Nizārī Ismailism is the Satpanth tradition of South Asia – this term (“True Path”) refers to the syncretic devotional practice that emerged when Nizārī Ismaili missionaries (called Pīrs) converted communities in medieval India. The Satpanth incorporated some Indic terminology and poetic literature (e.g., the ginān hymns) to express Ismaili concepts. The Khoja Ismailis of the Indian subcontinent are inheritors of this Satpanth tradition, though over the 20th century the Aga Khans encouraged uniformity and a move away from Hindu-influenced expressions towards more mainstream Islamic ones. There also exist small groups that broke away from the main Nizārī line; for example, in the late 19th century, some Khojas contested the Aga Khan’s reforms and became Twelver Shi‘a (the Aga Khan won a legal case affirming his leadership over the Khojas in 1866). On the Musta‘li side, aside from Bohras, the Sulaymānī branch in Yemen still exists in modest numbers. The Qasim-Shahi and Muhammad-Shahi Nizārī sub-branches were historical splits in the Imam’s lineage after Alamūt (eventually reconciled with the Qasim-Shahi line being the one of the Aga Khans). The term “Sevener” is often applied to Ismailis in general (because they broke at the 7th Imam) but historically some who were called “Seveners” actually stopped recognizing new Imams after Muhammad b. Ismā‘īl – essentially an early, now-extinct branch that awaited his return as Mahdi. This is sometimes conflated with Qarmaṭians. In the modern context, the Nizārīs and the Bohras represent the continuing Ismaili tradition within Islam, while the Druze represent an Ismaili-origin tradition now outside mainstream Islam. All these groups illustrate the adaptability of Ismaili ideas to different times and places – whether as revolutionary millenarian movements, grand caliphates, secret sects in fortresses, mercantile communities, or globalized minorities under a philanthropic Imam. Despite their differences, they share key Ismaili concepts such as the importance of the Imam or his substitute, and the belief in hidden meaning in the scriptures.

Ismaili Ethics, Community Life, and the Modern Imamate

Ismaili Islam is not defined only by its doctrines and history, but also by a strong ethical framework and distinctive community structures shaped by the Imam’s guidance. From the Fatimid era to the present day, Ismailis have emphasized values such as knowledge, justice, generosity, and unity. In the contemporary period, the Aga Khan (the title of the Nizārī Imams since the 19th century) has been instrumental in articulating Ismaili ethics in a modern idiom and organizing the community’s social governance. This section examines the ethical outlook, communal organization, and the role of the current Imam in Ismailism:

Ethics and Values: Ismaili teachings encourage believers to cultivate both spiritual purity and responsible citizenship in the world. A famous teaching attributed to Imam ‘Alī (also cherished by Ismailis) is: “Work for this world as if you will live forever, and work for your hereafter as if you will die tomorrow.” This encapsulates the Ismaili ethical attitude of balancing material responsibility with spiritual mindfulness. Pursuit of knowledge is a paramount virtue – historically, the Fatimid Imams sponsored scholarship and learning, and today Ismailis have high rates of education. They see learning (both religious and secular) as a form of worship and a means to better serve humanity. Honesty in business dealings and trustworthiness are strongly emphasized, especially since many Ismailis are traders or professionals who rely on reputation. Another key ethic is charity and compassion. The community is expected to care for its less fortunate and to contribute to the welfare of wider society. This is institutionalized through the practice of tithing (dasond), where Ismailis contribute a percentage of their income to the Imam’s treasury for philanthropic use. The Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN), funded in part by these contributions, exemplifies this ethic by running hospitals, schools, and development programs in some of the poorest regions of the world – an expression of Islamic compassion and social justice. Pluralism and tolerance are also notable Ismaili values. Because Ismailis have often lived as minorities and in diverse societies, the Imams have taught respect for other faiths and cultures. The current Aga Khan has often spoken about the importance of pluralism and seeing diversity as strength, aligning with the Quranic verse that God made nations and tribes to know one another (Q49:13). There is a spirit of optimism and balance between din and dunya (religion and world): Ismaili ethics discourage monastic withdrawal or extremist austerity, advocating instead a life of moderation, family responsibility, and community engagement. This ethic may be rooted in the understanding that since the bāṭin (inner spirit) is what ultimately matters, one can be in the world but not of the world – excelling in worldly endeavors while keeping one’s heart oriented to God.

Communal Structure: The Ismaili community (especially the Nizārī branch) has a well-defined structure that has evolved under the Imams’ directives. Unlike decentralized Sunni communities, Nizārī Ismailis are organized under a single hierarchy headed by the Imam. The present Aga Khan has established formal constitutions for the Ismailis in different countries, setting up councils and boards to manage communal affairs (education, health, economic development, religious training, etc.). Jamaʿat-khanas (prayer and community halls) are the center of religious life, functioning analogous to mosques but with certain differences in form – for example, in Nizārī Jamaʿat-khanas, men and women pray together rather than in segregated spaces, and the liturgy can include poetry and devotional songs in local languages in addition to Arabic prayers. The Ismaili community is transnational, so the Imam appoints National Council leaders in each region, who report up to the Imam’s secretariat (the Diwan). There are also spiritual functionaries like the Pīrs and Mukhīs (local prayer leaders or elders) who take care of ritual and pastoral needs. A unique aspect of Ismaili community life is the tradition of obedience and service to the Imam and the community. Volunteers (referred to as Khadim or servants) contribute countless hours in Jamaʿat-khanas, at community events, and in AKDN projects, reflecting a value of khidma (service) that is ingrained from a young age. Another notable practice is taqiyya (precautionary dissimulation) historically – in times of persecution, Ismailis would hide their faith or practice discreetly. While this isn’t an ethical principle per se, it influenced the community’s cohesion and cautious approach historically. Today, that need has lessened, and Ismailis openly celebrate their identity, though they remain a relatively private community. The Musta‘li Bohras likewise have a structured community led by their Dā‘ī, with local jamaats and a strong emphasis on hierarchy and obedience. They wear identifiable community attire (especially the Bohra women’s ridā veils and men’s distinct caps) and have their own communal funds and welfare systems. In both Nizārī and Musta‘li communities, there is a sense of one big family – titles like “Mawlānā Hāẓir Imām” (Our Lord, the Present Imam) for the Aga Khan or “Mawlāy” for the Dā‘ī indicate a protective, familial leadership. Social events like marriages, festivals (e.g., Eid and Imam’s birthday commemorations), and communal meals reinforce solidarity. Ethics such as honoring one’s elders, maintaining unity, and upholding the community’s reputation are stressed in community gatherings.

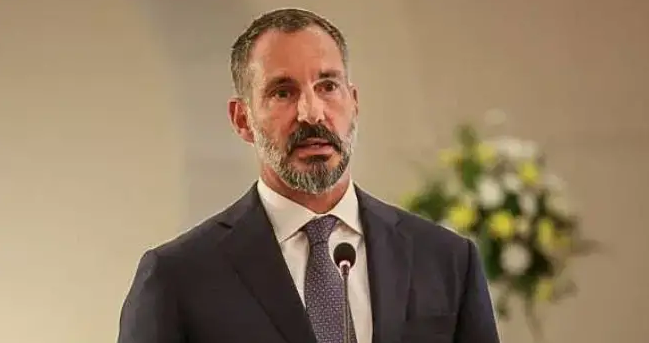

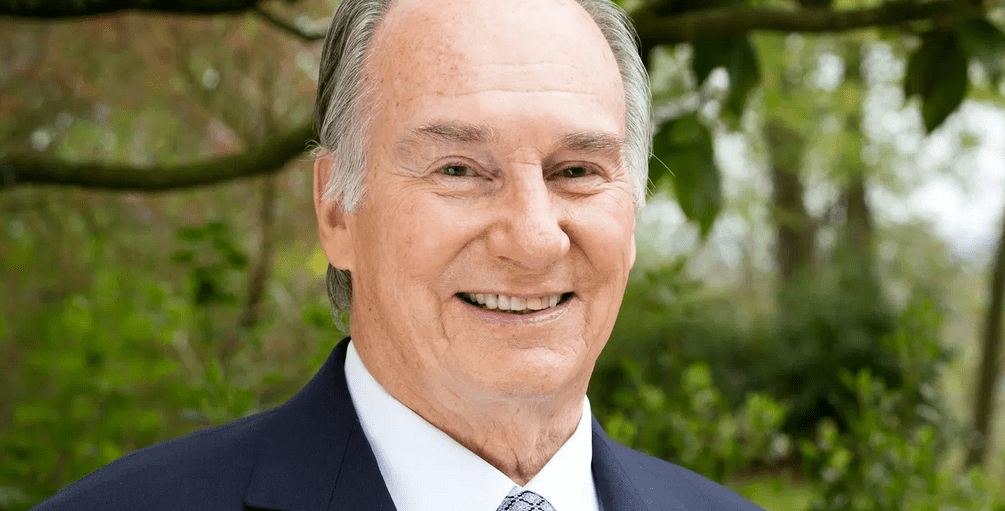

The Role of the Present Imam (Aga Khan IV): The Aga Khan, as the 49th hereditary Imam of the Nizārī Ismailis, plays an unparalleled role in defining modern Ismaili identity. Shāh Karim al-Ḥussayni (Aga Khan IV) assumed the Imamate in 1957 at the age of 20, and for over six decades he has led the community through significant changes. The Imam’s role is multifaceted: he is a spiritual guide, interpreting Islam in a way that is relevant to contemporary times, and he is also a statesman without a state, advocating for his community’s interests and for humanitarian causes on the world stage. The Aga Khan’s guidance comes in the form of farmāns (pronouncements) to the community, which may cover matters of faith (e.g. encouraging regular prayer, generosity, observance of ethical principles) or practical matters (emphasizing education, warning against fanaticism, advising on health or economic issues). One of his consistent messages has been the importance of keeping a balance between material progress and spiritual integrity – he urges Ismailis to be at the forefront of secular education and professional success, but to do so without losing their ethical compass. Under his leadership, the Ismaili community has invested heavily in institutions that reflect their values: the Aga Khan Development Network, which includes agencies for economic development, education, culture, health, architecture, and more, is among the world’s largest private development networks. Projects like the Aga Khan Rural Support Programs, University of Central Asia, Aga Khan University in Karachi, and the restoration of historic sites in the Muslim world all stem from the Imam’s vision of social conscience rooted in faith. He often describes these efforts as part of the mandate of the Imamate, that the Imam must improve the quality of worldly life for his community and the people among whom they live, in keeping with Islamic ethics of stewardship and charity.

In religious matters, the Aga Khan has guided reforms and interpretations that keep the Ismaili practice dynamic. For instance, during his grandfather’s time (Aga Khan III), the community’s rites were significantly modernized – the Du‘ā prayer was standardized, and many culturally specific customs were streamlined to give Ismailis around the world a unified set of practices. Aga Khan IV has reinforced the importance of Islamic pluralism and bridge-building. He has founded the Institute of Ismaili Studies (IIS) which works on preserving and studying Ismaili heritage and training religious teachers who can also relate to global contemporary issues. He has also established grand Ismaili centers (in London, Dushanbe, Toronto, Dubai, etc.) that serve as both places of worship and ambassadorial spaces showcasing Islamic art and promoting interfaith dialogue. The Imam’s person is central to Ismaili devotion – at gatherings, Ismailis will often recite a prayer for the Imam’s well-being and do didar (seek the Imam’s presence for a blessing). While Sunnis and others may not fully understand this relationship, for Ismailis it is the Imam’s guidance that guarantees the correct interpretation of Islam’s “essence” in every age. The present Imam has articulated that the essence of Islam is the search for enlightenment and social justice, and he interprets this essence through initiatives that uplift communities and foster understanding between religions.

Ethically, the Aga Khan’s influence can be seen in the way Ismailis have a reputation for integrity, philanthropy, and civic engagement in their respective countries. For example, Ismaili volunteers are often at the forefront of disaster relief alongside AKDN agencies. Culturally, he encourages Ismailis to be faithful Muslims while also being loyal citizens of their countries – there is an ethic of good citizenship, reflecting the belief that secular and spiritual responsibilities go hand in hand (a principle the Imam has referred to as the “dual responsibility” of Ismailis).

In conclusion, the modern Ismaili identity is a product of centuries of theological development and historical experience, crystallized under the direction of the Imams. The current Aga Khan epitomizes this by being a guardian of tradition and a reformer for modernity at once. Through his leadership, Ismaili Shi‘ism today demonstrates that a Muslim community can cherish its spiritual heritage – with deep roots in theological principles like tawḥīd, imamate, and ta’wīl – while also actively engaging in the global issues of education, health, poverty alleviation, and cultural dialogue. The ethics of the community, centered on compassion, knowledge, and justice, are thus lived out in concrete programs and daily practices. This synergy of faith and world, intellect and spirituality, esoteric insight and practical action is arguably the hallmark of the Ismaili interpretation of the “essence of Islam.” It shows a continuity from the classical Ismaili quest for hidden wisdom to the contemporary Ismaili quest to apply that wisdom for the betterment of humanity, under the guiding light of the Imam of the Time.

Conclusion

The Ismaili Shi‘ite tradition offers a compelling and multilayered understanding of Islam’s essence. It affirms the same core creed as other Muslims – the oneness of God, the mission of Muhammad, and the guidance of the Quran – yet it frames these within a cosmology of intellect and soul, and a theology of ever-living guidance through the Imamate. Ismailism’s distinctive focus on esoteric meaning (bāṭin) complements the exoteric form (ẓāhir), suggesting that the true fullness of Islam combines outward practice with inward understanding. In the Ismaili view, religion is a living reality that unfolds over time: God’s revelation didn’t cease with scripture, but continues to speak through the succession of Imams who interpret the immutable truths (ḥaqā’iq) in each era. This gives Ismaili Islam a dynamic character – it is traditional and scriptural, yet adaptive and intellectual.

Philosophically, Ismaili thinkers demonstrated that one could be committed to Tawḥīd while engaging deeply with human reason, embracing truths from philosophy and science as part of the God-given intellect’s domain. Mystically, they showed that understanding God requires purifying one’s inner perception, not just following external rites. And communally, they created a model where spiritual authority is unified (in the Imam) and used to guide ethical and material progress of the community. These features set Ismailism apart in the Muslim world, sometimes inviting criticism, but also producing a legacy of rich literature and stable, well-organized communities.

Ismaili Shi‘ism also throws light on the broader pluralism within Islam. By comparing it with Twelver Shi‘ism and Sunnism, we see how diverse the interpretations of Islam’s fundamentals can be – from legalistic and literalist to mystical and allegorical. Yet, the Ismaili example also shows a convergence: despite differences, Ismailis participate in the same basic religious life (they recite the Shahada, they pray and fast in their way, they commemorate Islamic history) and assert belonging to the Ummah. In recent times, greater recognition and dialogue have affirmed that diversity like that of the Ismailis is part of Islam’s tapestry, not outside it.

In essence, the Ismaili tradition teaches that Islam is a path of enlightenment: it begins with the affirmation of one God and the guidance brought by the Prophet, and it continues as a journey of seeking deeper understanding (ma‘rifa) under the auspices of the Imamate. The ultimate goal is to know God – an Infinite that can never be fully encompassed, but which shines through the intellect and the unveiled meanings of revelation. Accompanying this inward journey is an outward mission to establish justice and beauty in the world, reflecting the divine attributes. Thus, Ismailis strive to embody the faith through both contemplation and action. The present Aga Khan frequently emphasizes the Quranic ethic of improving the condition of society as a spiritual duty, illustrating how Ismaili theology directly informs its ethics.

The story of Ismaili Shi‘ism—from its early revolutionary fervor and complex cosmologies to its modern institutional philanthropy—demonstrates a remarkable continuity of purpose: to grasp and implement the true meaning of Islam (“asl al-islām”). That meaning, as seen by Ismailis, is ultimately the Oneness of God lived through the oneness of religion’s inner and outer aspects, under the guidance of those whom God appoints as lights along the path. In the Ismaili vision, this harmonious blend of divine unity, justice, knowledge, and guidance is the essence of Islam, an essence that remains ever-relevant and ever-unfolding.

Sources:

- Madelung, Wilferd. Ismaili Theology: The Prophetic Chain and the God Beyond Being amaana.orgamaana.orgamaana.org (on cyclical prophecy, Imamate, and eschatology).

- Madelung, W. (continued) – description of Ismaili Neoplatonism and God’s transcendence amaana.orgamaana.org.

- Wikipedia: “Isma’ilism” – overview of Ismaili history, philosophy, and differences en.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org.

- Wikipedia: “Twelver Shi’ism” – contrast in Imamate and Sharia views en.wikipedia.org.

- Britannica: “Isma’ilism” – discussion of zahir/batin and origins of Druze britannica.combritannica.com.

- Nanji, Azim. Ismaili Philosophy – IEP (Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy) iep.utm.eduiep.utm.edu (on ta’wil, Neoplatonism, and the cyclical view of history).

- Wikipedia: “Nizari Ismailism” and “Musta’li Ismailism” – information on branches and practices en.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org.

- Wikipedia: “Isma’ili practices” – differences in prayer, fasting, and charity en.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org.

- Daftary, Farhad. A Short History of the Ismailis (background on schisms and community developments).

- Aga Khan IV – public speeches and interviews (various) on pluralism, education, and the role of the Imamate in improving quality of life en.wikipedia.org. (These complement the above sources by providing contemporary context.)

Leave a comment